I have often pointed out that many of the so-called “tribal names” of the Orang Asli were creations invented largely for the convenience of British colonial administrators to classify and govern them.

When these colonial officers could not effectively communicate with the children of the forest, they turned to external naming (exonyms). As a result, some of these names carry ambiguity or even negative connotations until today.

Take the Orang Asli in Pahang as an example. Both the Semelai and Temoq tribes share oral histories of common ancestry, yet anthropologist Rosemary Gianno noted that the name “Temoq” was actually given by the Semelai, possibly derived from the Malay word tembok, which carries derogatory overtones such as “shabby” or “degenerate.”

The Che Wong tribe’s name has multiple origin stories and was once referred to as “Siwang.”

According to records, a British colonial officer, Ogilve, while serving in Temerloh, mistakenly thought a Malay forest ranger named Siwang was the name of a local tribe.

Others have suggested that “Siwang” was in fact a reference to the Orang Asli religious ritual Sewang, misheard or misunderstood by the colonisers and thus recorded as a tribal name.

As for the Temiar, who are found in the highlands of Pahang, Kelantan, and Perak, their name came from what the neighboring Semai called them.

Anthropologist Geoffrey Benjamin proposed that “Temiar” may have derived either from the Austronesian root tambir or the Mon-Khmer word tbiar, both meaning “the edge.”

From these cases, we see that although early Orang Asli societies did not have the concept of “race,” they already had a sense of “us” and “them.” Such distinctions were often expressed through mythological tales.

One upstream Urang Huluk in Johor once told me: in the beginning, the world had only a single well, and all humans drank from it. Later, someone wished for kopi O (black coffee), and the water turned into coffee.

Those who drank it became the darker-skinned Orang Asli and Indians. Someone else wished for teh tarik, and thus the Malays were born. Finally, when someone desired teh C (milk tea with evaporated milk), the Chinese people came into being.

Another Temiar elder in Kelantan told me: in ancient times, the Malay Peninsula was struck by a great flood that nearly wiped out all life. Only a brother and sister survived.

Orphaned, they floated on a raft and eventually settled on Mount Yong Belar, at the Kelantan–Perak border.

One day, the brother saw two lice mating on his sister’s head and suddenly grasped the mystery of reproduction. He then united with his sister, and from their offspring came the whites, the Orang Asli, the Malays, the Chinese, and the Indians.

Of course, such stories are the realm of anthropology. Archaeologists, by contrast, do not talk about “races” but instead classify people by eras and material evidence.

Into Kelantan’s Ancient Caves in Search of “Little Dancing Figures”

My first encounter with the Temiar was in mid-August this year. They were the ninth Orang Asli group I had met on the peninsula.

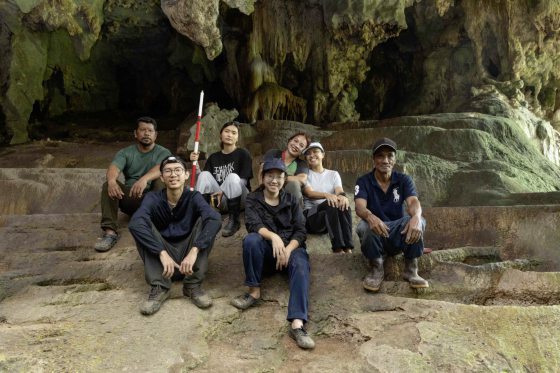

At the time, under the guidance of Malaysian archaeologist Dr.Saw Chaw Yeh, our five-member team ventured into several caves in Gua Musang, Kelantan, in search of prehistoric rock art.

Archaeologists, as specialists in material remains, rely on scientific methods to date, analyze, and reconstruct the life and rituals of prehistoric peoples through artifacts and cave paintings.

Meanwhile, my colleagues with backgrounds in anthropology and I spoke with the local Temiar community to trace connections between these rock paintings and contemporary oral histories—especially in interpreting the imagery and cultural context.

Within just three days, we explored three caves. Although these caves are near present-day Temiar settlements, some were located at high and difficult-to-reach spots.

It was only thanks to our Orang Asli companions, who cut tree trunks and built makeshift ladders on the spot, that we “city folk” could even climb up.

In archaeology, there is a general assumption: the harder it is to reach a rock art site, the more likely it was a place for rituals and communication with the spirit world.

One of our tasks was to find evidence confirming whether these caves were once sacred spaces for Sewang ceremonies performed by Temiar ancestors.

Indeed, in two caves we found numerous “dancing figures.” Some wore distinctive headgear called tempok, woven from certain leaves. Even more intriguing, most of the figures had only four “fingers.”

After debate, we speculated that these might not be fingers at all, but plants held in the men’s hands during ritual.

Dr.Saw admitted that her devotion to rock art studies comes from the realization that standing before these caves, what she sees is exactly what humans saw hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of years ago. This timeless gaze instills in her a sense of almost sacred responsibility.

Yet, the planned Nenggiri Dam may submerge Temiar villages, ancestral graves, and countless cave sites, making such encounters with ancient rock art impossible for future generations.

Orang Asli prayers: blessings beyond tribal boundaries

The day after leaving Kelantan, I drove three hours to a Temiar village in Perak.

Despite being just a few hundred kilometers apart, the landscapes were starkly different: Kelantan roads were lined with logging trucks, bald hills, and rivers the color of teh tarik, while Perak was lush with diverse vegetation, alive with the chorus of insects and birds, and blessed with rivers so clear one could bathe in them.

I was drawn here by chance through a dance collective led by Malaysian dancers and joined by both locals and foreigners.

They often connect with the Orang Asli to explore states of trance, seeking spiritual ties with the earth.

At the invitation of one member, Kien Faye, I was able to witness a traditional Temiar ritual.

According to Temiar belief, the 15th day of every month marks the tiger’s birthday, which must be appeased through a Sewang ceremony to avoid encounters with the king of the forest.

On the 20th and 30th, they hold rituals for the sky god Tampuy and the underground god Lulew, with prohibitions on hunting or gathering in the forest.

Coincidentally, August 20 also marks the Temiar Fruit Festival (Bering).

During the day, villagers gather at the ceremonial hall (balei), laying out an abundance of fruits—bananas, rambutans, mangosteens, jackfruit, and duku langsat—alongside the distinctive forest nut buah perah, crushed and roasted in bamboo, releasing a unique fragrance.

At nightfall, they return to the darkened hall for the Sewang Gelap ceremony.

That night, the Temiar sang twelve songs: the first few invoked the deities, the later ones called on the spirits of fruits.

Each song was led by men, while the women beat bamboo tubes in powerful rhythm, their voices resounding through the night sky.

Traditionally, such ceremonies were not open to outsiders. But because this international dance collective had sponsored the rebuilding of the Temiar ceremonial hall, they were welcomed as rare “guests of honor” and danced alongside the villagers.

Thanks to them, I moved from being a spectator to becoming a participant, drawn into that animist world through music and movement.

What touched me most was the leader’s deep, steady prayer before the ceremony began, calling for a year of abundance and peace.

Though I could not understand the Temiar language, within those unfamiliar syllables I caught familiar words: Malays, Chinese, Indians, and the eighteen tribes of the Orang Asli.

In that moment, I realized their prayers were not just for themselves but extended as blessings to all who live on this land. Across the barriers of language, I felt an extraordinary breadth of spirit—the gentlest and most embracing voice from the heart of the forest.

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT