Every time I venture into the wild and get bitten by a leech, I lose all motivation to explore the next day.

These bloodthirsty creatures love to repeatedly “kiss” the same spot, causing freshly healed wounds to become inflamed or even blister.

But since it’s hard to turn down invitations from the indigenous people, I have no choice but to pull on tight pants, spray insect repellent, and arm myself completely before stepping out.

When entering the rainforest, footwear must be chosen with care: closed shoes aren’t waterproof, and once you step into a swamp, a swarm of leeches will immediately latch on; hiking sandals have too many gaps, making it nearly impossible to pull leeches out once they sneak in; and as for rubber-tapping shoes—“Kampung Adidas”—crossing a river in them can turn them into a nursery full of baby leeches, leaving no room for defense.

The only choice left is to go barefoot.

Many indigenous people believe that walking barefoot provides better footing and stability while climbing.

Some aerial roots can even massage the soles of your feet—killing two birds with one stone.

More importantly, when a leech climbs onto the top of your foot, you can detect it immediately.

In any case, once they’re full, they’ll just drop off on their own.

However, what truly shocked me was that some indigenous friends would deliberately place leeches on their ankles, even on bruised areas, treating them to a feast.

When I asked why they would invite such pain, they simply shrugged and said, “We humans have taken so much from this world. Sometimes, we need to give something back.”

In fact, in medieval Europe, traditional healing methods were known as “leechcraft.”

Though the term might now be misunderstood as “the art of leeches,” in Old English, “leech” meant “to heal” or “doctor.”

Since doctors of that era often used leeches for bloodletting, the word gradually evolved into what we now know as “leech.”

But that brings us back to the question: Why does something so tiny inspire such intense fear in humans?

What is the connection between people and leeches—so much so that every shaman I’ve met insists that no spell can ward them off?

To answer that, we must start with the legends of the leech.

Mah Meri legend: It was all Moyang Melur’s fault

I’ve always loved the ancestral spirit masks of the Mah Meri tribe in Selangor. They’re carved from a rare wood called Nyireh Batu, and their prices rise year by year.

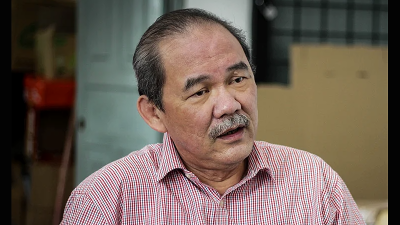

Whenever I have extra money, I ask master carver Abang Gali to make one for my collection.

Once, on a whim, I asked if he could make a Moyang Kelom (leech ancestor spirit) mask as a protective charm for the forest. He chuckled and replied, “Sure, I’ll carve one for you. But did you know humans are fated to coexist with leeches and mosquitoes? It’s all Moyang Melur’s fault.”

His wife, Kak Julidah, eagerly jumped in to tell the story.

According to the Mah Meri, the world has seven layers, and humans live on the sixth layer (tanah enam).

“A long time ago, Moyang Melur went into the forest to dig for cassava and accidentally broke into the fifth layer (tanah lima), where he encountered the demon Kayek, who nearly made a meal out of him.”

Just before being eaten, Moyang Melur quickly claimed to be an ancestral spirit.

Kayek stopped and presented him with a choice: “Do you want the small clay pot (belanga) or the large iron wok (kawah)?”

Moyang Melur chose the large iron wok—and was eaten anyway.

Later, another ancestor spirit named Moyang Betang went into the forest to search for his missing brother and also fell into the fifth layer, encountering Kayek.

Facing the same deadly question, he chose the small pot and thus survived.

Before leaving, Kayek warned him not to open the big iron wok, claiming it was full of poisonous insects. But Moyang Betang, driven by curiosity, lifted the lid and discovered his brother’s remains.

In hopes of resurrecting him, Moyang Betang carefully gathered the bones and reassembled them.

Then he asked a small lizard called mengkarung (skink) for a piece of old cloth and used its severed tail, inserting it into Moyang Melur’s nostrils to restore his flesh and bring him back to life.

As they were leaving the fifth layer, Moyang Betang warned him not to look back, but at the very last moment, Moyang Melur couldn’t resist.

With that one glance, he brought poisonous creatures—snakes, leeches, mosquitoes, and wasps—into the sixth layer, the human world.

Julidah exclaimed angrily: “Moyang Melur was such a jerk! Because of him, our descendants are still suffering!”

There are forces in this world that humans cannot tame—only respect with humility.

Jah Hut legend: The curse of Batin Bes

Canadian anthropologist Marie Couillard documented a leech legend among the Jah Hut people, which ties into their creation myth.

At the dawn of time, before the winds blew, two deities appeared: Peruman and Bra’il. Peruman came from the clouds, while Bra’il arrived from downstream. They met in the sky and argued over who was older.

Peruman was ultimately deemed the elder, and Bra’il was ordered to create the world.

First, he gathered sea foam to mold into a tray, forming the earth. Then he shaped humans from mud and asked Peruman to breathe life (nafas) into them.

However, out of curiosity, Bra’il peeked at the breath midway and accidentally let it escape. The second breath finally succeeded in creating the first human: Nabi Adam

But that first lost breath became the origin of all evil—transforming into Bapak Habli (Father of Evil).

His offspring included Sitan and Hablis, who led people to steal, drink, and commit adultery; Najis, who fueled carnal desires; and the evil spirit Bes, bringer of disease.

Among them, Bes is the most feared disease-bringer.

In Jah Hut heroic legends, Bongsu Kangcir, the youngest of seven brothers, seeks revenge after all his siblings are devoured by Bes.

He follows Bes back to their lair, tricks them into collecting tree resin (damar), and sets the entire village ablaze.

As the evil spirits burned, their leader Batin Bes cursed: “Our ashes will continue to trap human souls.”

To which Bongsu Kangcir replied: “Then I will use spells to call their souls back and drive away the disease spirits.”

Of course, Bes never completely disappeared—they transformed into mosquitoes, leeches, and lice.

No spell can repel them, and to this day, they remain the Jah Hut people’s most persistent sources of illness.

The power that cannot be tamed—only respected

I remember one time in the forest when both my feet sank into muddy swamp water, and I could feel a swarm of leeches stirring beneath.

I was about to scream when I noticed that the indigenous companions around me remained perfectly calm.

Perhaps my face betrayed my fear, because a Temuan friend suddenly said with great seriousness: “This is a path once walked by elephants. So, every step you take, you must tread with humility and gratitude.”

Just then, a breeze passed through. A falling leaf brushed softly across my cheek.

Almost instinctively, I removed my shoes and stood barefoot on the earth, quietly feeling the pulse of nature.

My steps on the way back felt much lighter. The elephant tracks before me seemed to bloom like a sacred path, filling me with awe.

At that moment, I understood: There are forces in this world that humans cannot tame—only respect with humility.

More on Echoes from the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT