Just before my phone signal cut off, I was listening to a podcast in the car. The hosts were discussing Spare, the memoir of Prince Harry:

“The first chapter records Harry’s birth. It’s said that Prince Charles told Princess Diana, ‘Wonderful! You’ve given me an heir and a spare—my work is done.’ Harry said that he was born to be William’s backup, in case…”

As the hosts’ voices faded away, the rattling noise from my shaking car grew increasingly harsh, making me feel as though I was driving one of those broken coin-operated rocking rides you find outside grocery stores—the kind that only works after you give it a good kick.

Looking toward the slope on the right, I saw a barren hillside strewn with large boulders—had there been a landslide here?

The road ahead was a mess. The jolting mountain path made me break out in a cold sweat.

If one of my tires got punctured by those sharp rocks, where would I even find a spare?

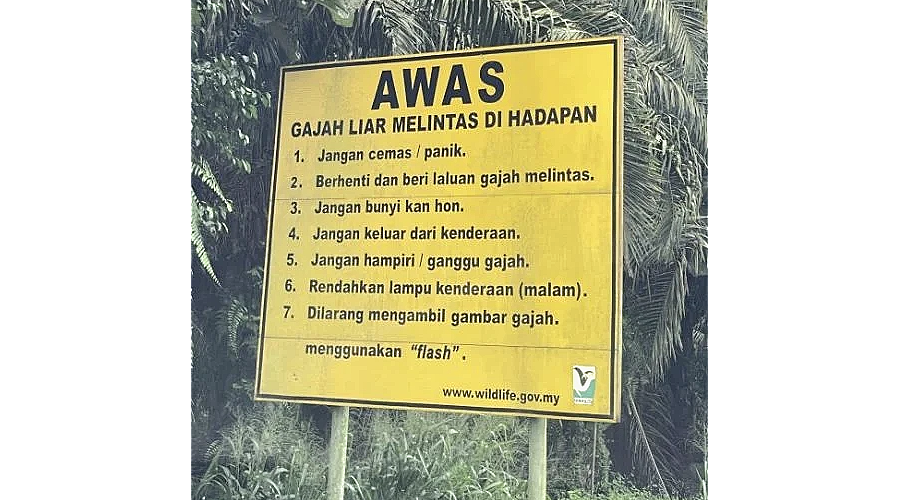

Every time I drive deep into the wild mountains of the Malay Peninsula to visit the Orang Asli (Indigenous people), I worry about a flat tire, an empty fuel tank, or running into ghosts, bandits, elephants, or tigers.

But the thing that troubles me most is losing my phone signal.

Once I’m cut off from the outside world, every problem has to be solved by myself. Even if I reach my destination safely, I can’t immediately let my family know I’m okay.

Over time, my parents have grown used to my “temporary disappearances.”

How do you let your loved ones know you’re safe with no signal?

Take the forest clinic in Endau-Rompin National Park (Johor) for example. I usually have to drive 40 minutes to an unremarkable oil palm tree just to make a call home—then another 40 minutes back to the clinic, returning to my isolated, off-the-grid life.

Sometimes, just to send a message, I run around the entire clinic like a madman—standing on tiptoe, holding my phone high, or lying flat on the ground.

Most of the time, there’s still not a single bar of signal.

In despair, I decided to follow local customs and learn to use kemenyan (benzoin resin) like my Orang Asli friends.

Many Indigenous people believe that the white smoke from burning kemenyan has magical powers—it drives away evil, purifies, and summons ancestral spirits.

So, during any ritual, there is always a charcoal pot burning kemenyan.

Besides purifying all the healing tools, every patient must waft a handful of smoke over their head and limbs three times before and after the ceremony.

Some even carry a piece of kemenyan with them into the forest; if anything happens, they can burn it for protection.

One morning, desperate and unable to find a signal, I decided to fumigate my phone with kemenyan smoke and recited a home-made spell:

“Plink-plonk, zap-zap, dear God, Buddha, spirits, please grant me one bar of signal—open the bridge to the outside world!”

I glanced at the top-right corner of the screen—no miracle. I tried reciting it again in Malay, but still, the words “No Signal” glared back at me.

When Farah, a Temuan patient, saw me muttering to myself in front of the charcoal pot, she interrupted the most “important ritual” of my life and asked what I was doing.

Embarrassed, I told her, “I was trying to use kemenyan to help my phone find a signal.”

They told me their phones had service and I could borrow one to call home. It turned out many of them use two SIM cards from different carriers—if one fails, the other usually works.

A few days later, I gradually realized that maybe the reason heaven turned my phone into a useless shell was to make me disconnect from the world’s noise—and return to the purest form of human connection.

Strangely enough, once I put my phone down, all my city-born anxieties— introversion, social fears—quietly vanished. And for the first time, I could see the most beautiful distance between people.

My safety relies on the kindness of my Indigenous friends

Of course, their care for me went far beyond that.

One early morning, I was observing a healing ritual by the Orang Huluk people. Out of nowhere, someone passed around watermelon for everyone.

I was happily eating my slice when suddenly a patient in the corner began screaming hysterically, as if possessed. I nearly choked on my bite.

An assistant quickly wafted kemenyan smoke over her, while the shaman began chanting spells.

At that moment, I was truly just a “melon-eating bystander” (as the Chinese idiom goes)—silently praying for her recovery.

But before long, it was my turn to suffer. My stomach began to ache violently—probably from eating watermelon in the middle of the night.

Farah noticed first. Seeing me clutching my belly, she dug out a bottle of medicated oil, rubbed it gently on my abdomen, and laughed:

“Don’t hold it in—if you need to fart, just let it out!”

A while later, another woman brought me a cup of warm water, saying the shaman had already blessed it.

I forced a smile and drank it. It tasted sweet and salty—maybe sugar and salt?

Just then, the chanting suddenly stopped, as if someone had hit pause. I looked toward the hall’s center—the shaman opened his eyes, returning from his trance, and the first thing he said was, “How’s your stomach?”

I touched my belly—it felt like two deflated balloons letting out a long “pfffft.” I couldn’t tell if it was the shaman’s magic—or simply that I had received too much love at 3 a.m.

Repaying kindness with a plate of chicken rice balls

After the four-day healing ritual ended, Farah and her daughter Lisa asked if I could give them a ride home. Of course, I agreed.

When I learned they lived in Melaka, I suggested, “Why not stop for some chicken rice balls first?”

To my surprise, they looked puzzled and asked, “What’s chicken rice balls?”

Their reaction shocked me—a Melakan who’s never had chicken rice balls? That’s like someone from Klang never eating bak kut teh, a Japanese person never tasting ramen, or a Korean never trying kimchi.

It made me wonder—are the everyday comforts of city people actually a kind of privilege?

Soon after leaving the forest clinic, I eagerly used my newly revived phone to search for “Jonker Street chicken rice.”

But then I faced a dilemma: going straight to their home would take an hour and a half; stopping for chicken rice balls first would double the trip to three hours.

Should I eat or not? My exhausted mind froze on the highway. I couldn’t hear Farah’s voice or even my own thoughts—until Lisa softly said, “I really want to try that chicken rice ball.”

At that, my reason snapped—I stepped on the gas and sped straight toward Jonker Street.

When we finally arrived, it was already 3 p.m. The usually busy tourist area was quiet, and most stalls had closed.

I began to regret my choice. But fortune favored us—at the end of an alley, one last restaurant was still open, glowing like a temple, saving our hungry souls.

Watching the mother and daughter eat their first-ever plate of chicken rice balls, I suddenly thought back to the past few days: when I ran out of clothes, got bitten by leeches, suffered stomach pain, or lost my signal, they were always the first to help me—and this was only our fourth day of knowing each other.

Was our four-day friendship worth much? I didn’t know. But as I insisted on paying the bill, I smiled and said:

“In the forest, you took care of me. Here in the city—let me take care of you.”

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT