Main causes of technician crisis include exodus of skilled workers, low social status, long working hours and low pay.

On July 2, Sin Chew Daily reported that Malaysia’s small and medium enterprises are facing the crisis of technical talent gap.

In order to work with the government to move forward in the present historic juncture of economic upgrading, the Merdeka Education Centre (MEC) proposed to develop in greater depth the mode of multi-technical training.

Its objective is to cultivate high-quality technical talents through school-enterprise cooperation plan to alleviate the current crisis of technician shortage.

This move by the MEC is not only to make up for the low 5% allocation provided by government technical and vocational colleges for ethnic Chinese youths, but it is obviously its keen interest to support and assist the government to meet the challenges head-on arising from the crisis.

At present, there is a serious shortage of qualified skilled workers in Malaysia because qualified skilled workers either go to Singapore to work and earn higher wages, or once they have accumulated enough capital and experience in their respective technical fields, they will start their own businesses and stop working hands-on using their acquired skills.

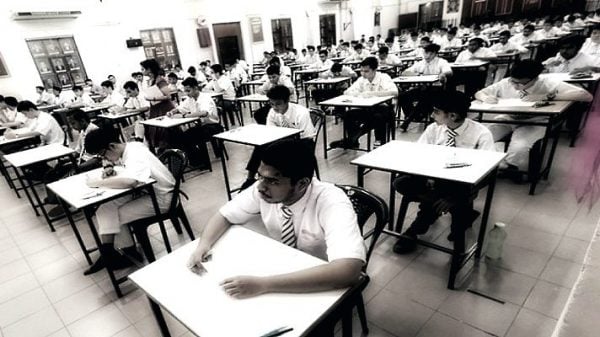

A common feature observable today is a local technician, qualified or not, who brings along with him foreign technical assistants to work, whether on construction site, house renovation or repair-maintenance of plumbing and electricity.

Foreign workers are generally on short-term contracts, most of whom have not formally done the above types of work before leaving for Malaysia.

They came to Malaysia through an employment agency and began to learn here and do repair or renovation work. They basically “learn by doing”.

Because foreign workers are not local citizens, and they usually receive a two-year work permit, they rarely have the opportunity to obtain technical training.

The skills they acquire can only be taught by their master technicians or more experienced co-workers.

Although some could have earnestly learned the skills, many have not acquired good skills. Under such circumstances, technical repair and maintenance work in Malaysia has not progressed well over the last 20 to 30 years, and it is common to hear complaints about poor and disappointing work.

There are at least two training levels for school-enterprise cooperation to cultivate technical talents.

The high-level category refers to the sophisticated and rigorous level training pertaining to the current knowledge economy.

As our economy upgrades itself in the midst of industrial-technological development, the high-end service industry and other research and development industries are increasingly connected to applications of artificial intelligence, the Internet, and cloud computing.

These new and high level technologies are constantly being upgraded to promote and improve the technical production and management capacity, so as to strengthen the corporate competition in the global economy.

The other category as it was proposed by the MEC is obviously the general-level plan already in existence in Malaysia for decades, known as the Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET).

What the MEC most interested is in to develop, inter alia, training in baking, cookery, hairdressing, catering management, plumbing, electrical and vehicle maintenance, air-conditioning, as well as construction and renovation works.

The basic belief of school-enterprise cooperation is to have a follow-up for students after their classroom learning, by sending them out to enterprises to do practical work. Students’ practical work serves to link their theoretical knowledge with real work on the ground.

It serves also as a test if classroom teaching corresponds with the real world, and where missing links are found, school curriculum should be updated and teaching improved.

At present, the practice of school-enterprise cooperation still faces many difficulties and challenges in the Malaysian society.

Apart from the relatively low social status of skilled workers, technician shortage is also due to the low pay of blue-collar workers despite some recent increase as a result of high inflation rates. In Malaysia, the salary gap between blue-collar skilled workers and white-collar professionals is indeed quite large.

Take Australia’s salary statistics as an example. In 2022, the median annual salary of experienced technicians in Australia is about A$72,000 (RM215,000), and the average annual income of electrical workers is A$85,800 (RM257,000). As to white-collar university teachers, their average annual income is A$108,000 (RM324,000).

In comparison, the salary gap between Australian technicians and university teachers is not too large!

Although skilled workers in Australia receive less formal education than university lecturers, they make a decent living with their skills, and enjoy many opportunities for lifelong technical training, with some offering them professional diplomas.

In terms of social status, by providing a relatively high level of service quality, they earn good respect from the society.

In Malaysia, many parents want their children to study a professional degree in university, and they would feel a sense of frustration when their children go to technical schools and work in blue-collar jobs.

Children who do not like to study but if forced to take up technical courses may not be necessarily serious.

I think if this phenomenon is common among Malay teenagers, ethnic Chinese and Indian teenagers are also believed to have the same problem, and this is an important factor leading to unsatisfactory quality of technical services.

It is of general view that many young Malay technicians trained at government institutions get tired after working some years as blue-collar workers, especially those involved in the 3D types of work (dangerous, dirty and difficult). Many quit and change career.

Under present circumstances and social environment, there are not enough local young people joining technical training, resulting in vacancies being filled up by unskilled or semi-skilled foreign workers.

This has further worsened the crisis of technical talent gap in local small and medium-sized enterprises.

To sum up, there are four main causes of the technician crisis in Malaysia, namely the exodus of skilled workers to Singapore, relatively low social status of skilled workers, technicians’ long working hours and fatigue, and the low pay for skilled workers, especially when they work as apprentices.

In view of this, apart from further strengthening the cooperation between vocational colleges and enterprises in planning and training to ensure that students can learn relevant skills required by enterprises, the government and private sector have to find ways to improve systematically the working conditions of skilled workers.

With better conditions, blue-collar workers will take pride in the jobs they do and win the respect of society.

One of the many ways is to impose stringent control of blue-collar qualifications.

I think as long as technicians have a sense of responsibility and continuously improve their professional knowledge and service quality, Malaysia will move successfully towards a more advanced stage of development with an increasingly solid base of knowledge economy.

When we have high-quality technicians with a professional spirit of excellence, our technicians would soon earn higher reasonable incomes closer to those like Germany or Australia.

Their self-esteem and social status will definitely improve over time.

(Wong Tai-Chee has his B.A and M.A degrees in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Paris, and earned his PhD in Human Geography from the Australian National University. After teaching 20 years in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, he retired in 2013. He then worked as Distinguished Professor for two years at Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, China, and as Dean and Professor at the Southern University College, Johor until the end of 2018. He was Visiting Professor to University of Paris (Sorbonne IV), Visiting Fellow to Pekin University, Tokyo University and University of Western Australia. His main research interests are in urban and economic issues, and more recently on Malaysian politics. Besides his 15 self-authored and edited book volumes, he has written over 100 academic articles and published widely in international journals.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT