During the last 400 years of modern history, the scale and substance of world emigration have undergone earth-shaking changes, of which two models are the most representative.

One is the European expansion model associated with its open maritime, capitalistic and colonial civilization, which is underlain by an external-oriented economic exploitation. The typical representative country is the United Kingdom.

The other is the agriculture-led civilization of China, where the content and purpose of emigration are basically different from the former.

The European maritime-driven model represented by the United Kingdom encouraged colonial expansion, supported and utilized their own people to occupy foreign land and acquired political advantages by force, thereby obtaining colonial exploitation rights and wealth.

On the other hand, due to the fact that the land-oriented and closed-door Chinese agriculture-based feudal civilization lacked the conceptual interest for capitalist economic exploitation, it had virtually no motivation towards overseas colonization.

Whilst Feudal China was happily contented with its long tradition of receiving foreign tributes, it regarded its people as the property of imperial power and prohibited them from emigration.

The sources of exploitation and wealth accumulation by the imperial court and landlords continued to stay at home, mainly from the peasantry and small groups of merchants.

Differences between Chinese and British emigrants

Comparing Britain with China, the two countries have huge differences in land mass and population size.

The British population was only five million in the early 18th century, and as a result of the Industrial Revolution accompanied by rapid urbanization and material growth, its population had increased to nine million by early 19th century.

Almost at the same period, China’s Qing Dynasty, after going through 130 years of prosperity under the reigns of three emperors, Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong, saw its population increasing from 80 million to about 300 million.

The food needed for China’s massive population growth was partly due to the introduction of more drought-tolerant crops from the New World of America, such as corn, sweet potato and potato, and mainly by opening up relatively barren lands or mountainous areas to grow food.

Indeed, the substantial increase in population had increased the aggregate wealth for the agrarian-based Qing dynasty. But to individual farmers, this would mean that for a country like China with much mountainous terrains and barren lands, the share of arable land per head tended to decline.

Consequently, more farmers had to move to ecologically fragile areas or to build terraced fields along hill slopes to cultivate crops.

Those living closer to coastal areas would find opportunities to move overseas when they had to.

As far as emigration policy is concerned, there is a huge difference between land-oriented China and maritime-oriented Britain.

Although the British territory and population were both small, the number of British people who emigrated over the past 300 years was much larger than that of China.

Scholars estimate that from 1801 to 1925, China sent away three to five million laborers overseas. Most of these emigrants were male, and they left without bringing along their family members.

In the case of Britain, however, during the 100 years from 1815 to 1914, about 15 million people left and many of them in families.

With so many British colonies overseas, the British chose to settle down in areas with climates that suited them, such as the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

Behind Chinese and British migratory movements, there were two markedly different government policies and attitudes towards their own migrants.

After the defeat of the Sino-British Opium War in 1842, the Qing government relaxed the policy of prohibiting out-migration, but took an indifferent attitude towards emigrants.

Basically no service centers or offices were set up in Chinese settlement areas overseas, let alone taking up the responsibility to protect them. On the contrary, the Western colonial governments normally established the “Chinese Kapitan” system in some areas of Southeast Asia to assist the colonial government in managing overseas Chinese affairs.

Most of the Chinese emigrants in the second half of the 19th century were peasants forced to migrate because of poverty or landlessness, except for a small number of freelancers.

They were self-reliant in the overseas territories where they lived, and relied on organizing secret societies, clan associations and guild houses to provide mutual support for self-protection and making a livelihood.

In the absence of government support, many Chinese emigrants had suffered tremendously and misfortunes that could not be accounted for in words.

In his 2009 book “Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times”, Philip A. Kuhn described the history of Chinese emigration to the world over the past 500 years with a historical and narrative perspective.

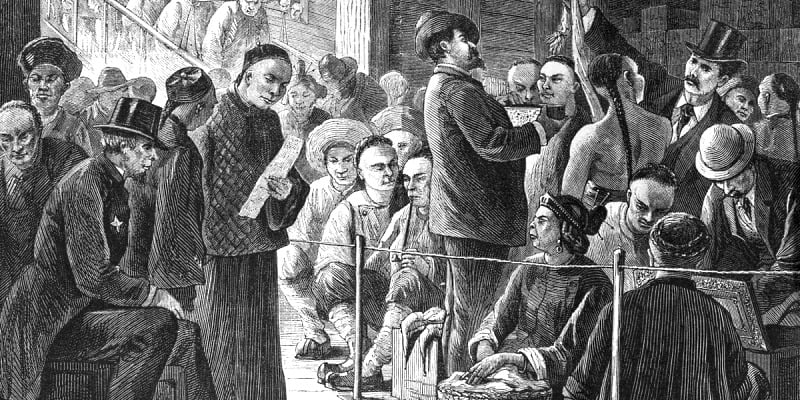

The key point of Professor Kuhn’s presentation is that most of the areas where the Chinese emigrated were colonies ruled by Western powers, and they formed a middle-class society sandwiched between the colonial rulers and the local indigenous peoples.

Although the overseas Chinese were enslaved subjects, among them there were intellectual elites who had strong Chinese nationalism passion, business tycoons and small people who just managed to survive with their families.

These “Chinese” had intricate interactions with the colonial rulers and natives in and around the settlements, and being regarded as outsiders, the overseas Chinese needed to understand them and lived with them through an experience of both competition and confrontation.

But the Chinese emigrants had never been in a politically dominant position, as they always regarded themselves as Chinese overseas, attached to the Greater China regime in their place of origin.

No matter how bad and disregard the regime might have treated them, they were willing to show love and support to that regime without any regret, and to provide financial assistance in times of crisis without asking for rewards.

In sharp contrast, British emigrants were the vanguards or forefront fighters for the British colonization campaign. From the colonies, they provided the necessary raw materials, food and markets in support of the British industry and global business.

Unlike the helpless Chinese emigrants, British emigrants not only had the support of their motherland, they also participated in the African slave trade in the Americas, and their enslavement in cotton fields and sugar cane plantations.

Sometimes, they were also actors in the slaughter and deportation of vulnerable native groups, recording a barbaric page in the history book.

It’s in this way that British emigrants came to dominance by force, whereas the Chinese emigrants who had no force or had only self-inflicted fights among their own factions or secret societies were destined to be controlled by others or face discrimination.

It is ruthless to say that history is written by violence, but violence has created faits accomplis countless times in history. This is indeed a tragedy of the evolution of human society.

Another distinct difference between British and Chinese emigrants was that British emigrants had a strong will to break away from their home country and become independent. On the contrary, Chinese emigrants have carried with them the psychological burden of China’s two thousand years of tyranny.

Such subconsciousness of “imperial loyalty” is deeply influenced by the Confucian unification thought of one China and ethnic-cultural lineage.

Sadly to say, many today still believe that such orthodoxy is correct to follow.

In conclusion, it reminds me of what Lu Xun, a great Chinese writer, said about the natural servility of the Chinese (including overseas Chinese).

As he said, even though they are slaves, they do not realize that they are slaves, they still take it easy, they still need to safeguard face, and they seek spiritual victory (the spiritual victory of China’s growing strength).

Lu Xun’s severe judgement sounds very uncomfortable or even unacceptable, but it should be worth a reflection on us!

(Wong Tai-Chee has his B.A and M.A degrees in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Paris, and earned his PhD in Human Geography from the Australian National University. After teaching 20 years in Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, he retired in 2013. He then worked as Distinguished Professor for two years at Guizhou University of Finance and Economics, China, and as Dean and Professor at the Southern University College, Johor until the end of 2018. He was Visiting Professor to University of Paris (Sorbonne IV), Visiting Fellow to Pekin University, Tokyo University and University of Western Australia. His main research interests are in urban and economic issues, and more recently on Malaysian politics. Besides his 15 self-authored and edited book volumes, he has written over 100 academic articles and published widely in international journals.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT