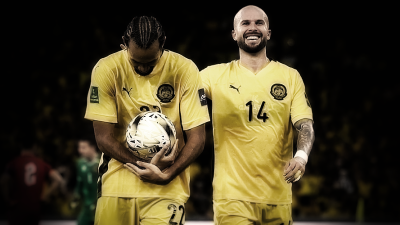

In a country where scores of thousands of genuine Malaysians have spent years begging for recognition, it took a group of foreign footballers just a few months to become Malaysians.

Their Bahasa Malaysia was so limited that they admitted to FIFA they couldn’t read the very documents they supposedly signed.

Yet according to the Football Association of Malaysia (FAM), these same players passed a Bahasa Malaysia test, recited an oath in the national language, and walked out with shiny new MyKads and passports.

For many Malaysians, especially non-Malay Malaysians who grew up hearing “citizenship is a privilege, not a right,” the scandal is not just shocking, but also equally painful and an insult.

What this episode reveals is not simply cheating in football. It reveals the existence of a two-tier citizenship system: one for ordinary Malaysians, and another, far more convenient lane for those with the right connections, the right utility to an institution, or the right moment in a political calendar.

The facts disclosed by the FIFA appeals committee are damning in their clarity.

All seven “heritage players” admitted they cannot speak Bahasa Malaysia, and could not even read the paperwork involved in their citizenship applications.

FIFA found no credible evidence that any of them had Malaysian ancestry.

In multiple cases, documents submitted by FAM contained clear signs of alteration such as misspellings, blurred fields, missing verification codes, and birthplace changes that conveniently transformed “Spain” into “Malacca.”

FAM’s own secretary-general admitted that staff made “administrative adjustments” to foreign birth certificates.

Yet the Home Ministry approved their applications with unprecedented speed. Two players were scouted in 2024, invited for paperwork in early 2025, and had their citizenships in hand by March that same year.

No Malaysian mother trying to register her overseas-born child has ever seen such efficiency. No stateless Indian Malaysian who has lived here for 60 years has been offered such discretion. No Orang Asli elder or Penan child without a birth certificate has ever been ushered through citizenship procedures with this kind of urgency.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the players’ applications succeeded not because they met the requirements, but because someone wanted them to succeed, meaning in super quick time.

For decades, Malaysian citizens who are not ethnically Malay have learned to temper their expectations where citizenship bureaucracy is concerned.

Chinese Malaysian children born overseas to Malaysian mothers were denied citizenship for decades due to discriminatory laws, only recently overturned by the courts.

Stateless Indians who can trace their presence here back generations remain stuck in administrative limbo. Indigenous communities who are the very first peoples of this land, are often unable to secure documentation because their parents never registered births under a system designed without them in mind.

Yet these communities are told to be patient. To show proof. To comply with impossible requirements. To wait while files gather dust. They are reminded that citizenship is not automatic, not guaranteed, and not an entitlement.

But for the FAM players, citizenship suddenly became a strategic tool, read a fast-tracked convenience.

This scandal strikes at something deeper than football. It wounds the national trust that citizenship laws are applied fairly. It challenges the integrity of the institutions responsible for safeguarding our identity documents. It raises uncomfortable questions about political discretion: Why was it used so swiftly for foreign athletes, but withheld for actual Malaysians?

And make no mistake: this is not an anti-foreigner sentiment.

Malaysia has welcomed migrants for centuries. Many of us are the descendants of people who traveled far to build new lives here.

The issue is not whether foreigners can become Malaysians. The issue is whether the law applies equally. More importantly, it’s whether citizenship is being treated as a tool for convenience rather than the sacred recognition of belonging it is supposed to be.

The Ministry now owes the rakyat a transparent account of how these applications were approved.

Were the language tests administered? Were the documents verified? If alterations existed, who authorized them, and why? And perhaps most importantly: Why was ministerial discretion used here, when thousands of genuine Malaysians have begged for that same discretion and been denied?

This moment should be a turning point. Not to punish footballers who may have simply followed instructions, but to confront a system that appears to bend easily for some while remaining rigid and punitive for others.

Don’t Malaysians deserve a citizenship process that is transparent, accountable, and rooted in equality and not one that changes shape depending on whose application is being processed?

We are not just a statistic. We have roots in the country and we identify with others who call ourselves Malaysians.

The scandal may have started on a football field, but its consequences touch the very core of our national identity.

If citizenship can be fast-tracked by influence, altered documents, or sporting ambition, then what does Malaysian citizenship really mean? And who, ultimately, gets to belong?

This is a national embarrassment, made even worse because the Madani government, which promised reform, rule of law and proper governance, has completely failed us.

Their incompetence is shameful!

(Mariam Mokhtar is a Freelance Writer.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT