Not long ago, I gave a talk at a local Chinese independent high school. A teacher told me that students today have increasingly poor language skills. First, many young parents prefer to speak English with their children, resulting in weak command of their mother tongue.

Second, since these parents themselves do not come from English-medium backgrounds, their children’s English still cannot match those who attend international schools.

Third, there are too few non-Chinese students in Chinese independent schools, depriving students of an environment to practise Malay.

For these reasons, many graduates of Chinese independent schools end up in an awkward position when it comes to further studies:

Thinking of studying in Western countries? Their English isn’t fluent enough.

How about study in China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan? Their Chinese isn’t necessarily strong.

Stay in a local university then? Their spoken Malay is often completely inadequate.

As a graduate of a Chinese independent school, I admit that mastering three languages is not easy. Malaysian Chinese like to boast that we are linguistic geniuses, but in reality, very few students can effortlessly master multiple languages.

For instance, my weakest subject in secondary school was actually Chinese. Perhaps because my parents only enrolled me in English and Malay tuition classes, I did well in those two subjects, but only got a B in Chinese in the Senior Unified Examination.

It wasn’t until after graduating from high school, during my three months of national service, that I realised the “Malay” I learned in school was nowhere near enough for effective communication with Malay peers.

To begin with, Malays do not necessarily use affixes (imbuhan) in everyday speech, and online slang is even harder to decipher with Google Translate.

For example, they shorten “tak apa” to xpe, “welcome” to sama2, and say korang instead of the formal kalian, by slurring kau (you) and orang (people) together.

To the 19-year-old me, this was a major “culture shock”—as if I was only then discovering the real Malaysia. After that, I started studying my Malay friends’ Facebook posts and comments to understand their language habits, hoping to better understand the Malay worldview.

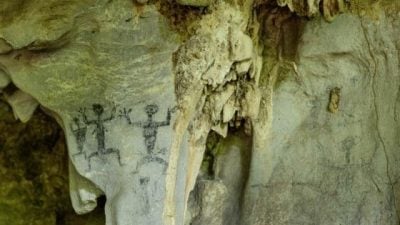

However, once I ventured into the tropical rainforests of the peninsula, this approach no longer worked, because many Indigenous groups are non-literate societies. Add to that the fact that there are 19 tribes with 19 different languages, and each time I entered a new village, I had to learn an entirely new mode of communication.

As a result, I experienced many moments of complete miscommunication.

The Origins of Austroasiatic vs Austronesian

Broadly speaking, the Indigenous peoples of Peninsular Malaysia can be divided into two groups: Austroasiatic and Austronesian.

The Negrito communities of northern Malaysia and the Senoi communities in central Malaysia speak Aslian languages, belonging to the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic family. Anthropologist Geoffrey Benjamin notes that these languages predate Malay and can be divided into four main branches:

Northern Aslian: Kensiu, Kintaq, Jahai, Mendriq, Batek, Che Wong

Central Aslian: Mah Meri, Semai,

Southern Aslian : Mah Meri, Semak Beri,

Independent branch: Jah Hut

Because these languages trace their origins to the Mon and Khmer people of present-day Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, and Cambodia—some of Southeast Asia’s oldest ethnic groups—a Semai friend once told me that when he travelled to Cambodia, he discovered that their language still shares similar vocabulary and grammatical structures with Khmer.

As for southern Malaysia, the Proto-Malay groups include Temuan, Jakun (also called Orang Hulu), Orang Kanaq, Orang Seletar, Orang Kuala, Semelai, and Temoq. Their languages mostly belong to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian family, related to Malay, and according to linguistic theories, their ancestors are widely believed to have originated in Taiwan.

The languages of the northern and central groups differ significantly from Malay and are especially difficult to learn. By contrast, Proto-Malay languages are structurally similar to standard Malay, commonly following a subject–verb–object (SVO) order.

Some local scholars have found that the cognate rate between Jakun, Temuan, Orang Kanaq, and Orang Seletar and Malay exceeds 85%, meaning they can be considered dialects of Malay sharing a common ancestor, Proto-Malayic. Orang Kuala shows only 80.9% cognacy—below the 85% threshold—and is thus classified as a separate language, although still within the same family.

Interestingly, although Semelai and Temoq are categorised as Proto-Malays, their languages are actually South Aslian, reflecting a colonial-era classification that prioritised physical and cultural similarity to Malays.

Anthropologist Rosemary Gianno found that Semelai people gradually abandoned their own language due to extensive trade and intermarriage with Malays.

Meanwhile, Peter Laird observed that Temoq shamans would sometimes borrow Malay or Jakun incantations in healing rituals to compensate for their lack of knowledge—occasionally leading Jakun shamans to accuse them of plagiarism.

Entering the world of indigenous languages: starting with “How Are You?”

So how did I communicate with these different tribes? The most straightforward answer, of course, is Malay. But if you truly hope to enter their world and show sincerity, learning their languages is the best way.

Honestly, when I first engaged with indigenous communities, I didn’t realise the importance of learning their languages. But the deeper I went into the interior, the more I realised that many tribes are not fluent in Malay.

We often ended up miscommunicating, sometimes relying on hand gestures to get our point across.

For example, a Jah Hut shaman once told me they used a type of wood called kayu tutu to carve puppets that capture evil spirits. Unable to confirm its scientific name, I temporarily translated it as “tutu wood.” Later, after probing further, I realised that tutu simply means “soft wood” in Jah Hut, and does not refer to a specific plant.

On another occasion in a Semai village, several elders tried to explain how to chop herbs with a knife but didn’t know how to express “cutting.” So they mimed the action while repeatedly saying “ching chong ching chong”—and to my surprise, I actually understood.

Questions like “How old are you?”, “How long does it take to get from the city to the village?”, or “How much does this cost?” often elicited baffling answers.

A Temiar friend once told me that their language only has the numbers “one, two, three” (ne, nar, nek), and the rest must be borrowed from Malay. Half -jokingly, he said, “Maybe the teacher died before finishing the rest of the numbers!”

But I prefer to think that their lack of numerical vocabulary has to do with their subsistence lifestyle. When there is little large-scale exchange of goods, there is naturally no need to develop a system of “big numbers.”

You can also see the convergence between Austroasiatic and Austronesian cultures in everyday greetings.

For instance:

Batek: Aileu khabar?

Jah Hut: Mende khabar?

Mah Meri: Namak khabar?

There are also greetings with entirely different words.

For example:

Semai: Mai gah?

Temiar: I lok gah?

So when I meet Indigenous friends from different tribes, I greet them in their own languages as a sign of respect.

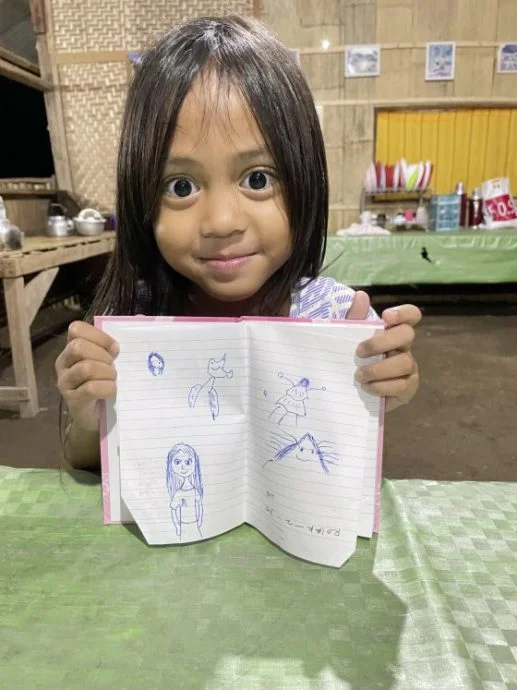

What touches me most is that many young Indigenous people who attended Chinese primary school like to speak Chinese with me. Even deep in the rainforest, their Chinese brought me a sense of familiarity.

More importantly, these “language exchange” moments remind me that communication is not about grammatical correctness, but about the willingness to bridge the gap between people.

More on the Echoes of the Forest

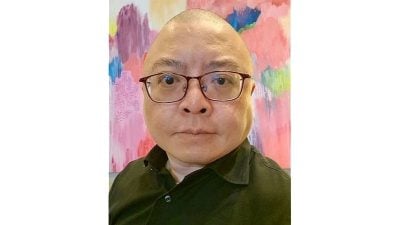

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT