Every Malaysian knows the drill. Whether it is a school registration form, a university application, a government scholarship, or even a simple survey, the first questions often demand the same information: race and religion.

For decades, these boxes have been quietly filled in by millions of Malaysians.

To be fair, there are contexts where such information is necessary. For example, in population censuses, for targeted health data, or for matters relating to religion itself.

But what troubles many Malaysians is the routine demand for these details in areas where they seem unnecessary: in education admissions, job applications, or basic public services.

With each tick of a box, an unsettling question arises: why must our identity, in all its complexity, be reduced to these two categories, even when they are irrelevant to the opportunity or service at hand?

As Malaysia marks its 62nd Hari Malaysia, it is worth asking why race and religion remain institutionalized in our forms and systems, and what this reveals about the unfinished work of nation-building.

Far from being a neutral exercise, the act of categorizing Malaysians by race and religion shapes opportunities, reinforces hierarchies, and conditions how we see one another.

The insistence on recording race and religion is not accidental. It has deep roots in Malaysia’s colonial and postcolonial history.

Under British colonial administration, communities were classified along racial lines: Malays were associated with agriculture, Chinese with commerce, and Indians with plantation labor.

These categories were never neutral descriptors; they were tools of governance that maintained divisions while facilitating control.

As we are aware, there are still debates today about when Malaysia’s true “independence” should be marked: in 1957, when the Federation of Malaya gained sovereignty, or in 1963, when Malaysia was formed with Sabah, Sarawak, and (briefly) Singapore.

Both moments are significant, but they also set the stage for how race and religion were managed in the new nation.

The 1957 Constitution enshrined the special position of Malays and other Bumiputera groups alongside guarantees for other communities, a compromise often described as the “social contract.”

Yet the optimism of those early years was shaken by the 1969 riots, after which the New Economic Policy (NEP) was introduced in 1971 and fully institutionalized by 1973.

While the NEP helped to reduce poverty and expand the Malay middle class, it also entrenched racial identification as a permanent feature of governance, making race not just a matter of identity but a gatekeeper to education, housing, and employment opportunities.

This legacy lives on in today’s bureaucratic practices. To apply for a government university place, a housing loan, or a civil service position, one must still declare race and religion.

What was once designed as a temporary corrective measure has become a permanent fixture of Malaysian life.

Everyday implications: More than just a box

Some argue that filling in race and religion is harmless, as a mere bureaucratic formality. Yet the implications are far-reaching.

These categories do not just sit on paper; they determine outcomes.

Consider the case of UPU university placements, which dominate headlines each year.

Admission quotas are structured around racial categories, with Bumiputera students receiving a designated share of places. This means that the simple act of ticking “Chinese” or “Indian” already shapes the horizon of possibility for many students, regardless of merit.

Similarly, government scholarships and financial aid schemes are often structured along racial lines.

For families who do not fall into preferred categories, the act of ticking the wrong box can mean exclusion, pushing them towards costly private alternatives or opportunities abroad.

Religion, too, plays a role. From registering a marriage to applying for identity cards, the state’s emphasis on religion creates rigid boundaries, particularly between Muslims and non-Muslims.

This has direct implications for legal matters, such as custody disputes or conversions, where the state often prioritizes religious identity over individual choice.

The everyday reality is this: ticking a box is not neutral. It is a mechanism that opens some doors and closes others.

Beyond structural outcomes, there is also a psychological burden.

Being constantly asked to identify by race and religion reinforces the sense that Malaysians are defined first and foremost by these categories, rather than by shared citizenship.

For many young Malaysians, especially those born into a generation that identifies more with shared cultural references, such as K-pop and TikTok, than with rigid racial categories, this feels outdated.

It locks them into identities they may not fully embrace, and it prevents the evolution of new, more fluid forms of Malaysian belonging.

The persistence of these boxes also creates discomfort for those whose identities do not fit neatly into prescribed categories.

Children of mixed marriages, for example, often struggle with forms that demand a singular racial identity.

Similarly, individuals with complex or evolving religious affiliations find themselves forced into narrow categories that do not reflect their lived realities.

Defending the practice: Arguments and counterarguments

Supporters of maintaining race and religion in official forms often present two arguments.

First, they argue that Malaysia’s diversity makes such categorization necessary for governance and planning. Without recording race and religion, they claim, how can the government ensure fair representation in schools, jobs, or politics?

Second, they argue that these categories are essential for preserving the “social contract,” ensuring that constitutional provisions for Bumiputera privileges can be implemented effectively.

While these arguments carry historical weight, they falter under scrutiny. Other multicultural societies manage diversity without constantly demanding racial declarations.

In countries like Canada or Singapore, while ethnicity may be recorded in censuses, it is not a prerequisite for accessing every public service or opportunity.

Governance can be achieved through need-based, rather than race-based, policies.

Moreover, tying rights and opportunities so tightly to racial categories perpetuates division rather than addressing inequality.

It risks creating resentment among those excluded and dependency among those included, undermining the very social cohesion it claims to protect.

Signs of change: Small shifts, big debates

Despite resistance, there are signs that Malaysians are increasingly questioning the necessity of these boxes.

In recent years, petitions have circulated online calling for the removal of race and religion from official forms, especially in school and job applications.

Civil society groups argue that such data collection perpetuates discrimination and undermines the spirit of equality enshrined in the Federal Constitution.

Some institutions have taken steps. Certain private universities and companies have begun removing race and religion from application forms, focusing instead on qualifications and skills.

These moves, while limited, signal a growing awareness that identity should not determine opportunity.

Yet resistance remains strong. Proposals to remove race from school forms have been met with political backlash, framed as threats to Bumiputera rights.

The debate is polarized: for some, removing the boxes signals progress towards a more equal Malaysia; for others, it is perceived as dismantling a hard-won system of protection.

To argue for the removal of race and religion from forms is not to deny the persistence of inequality.

Structural disparities exist and must be addressed. But the real question is whether racial categorization is the best way to address them.

A more nuanced approach would focus on need-based policies, targeting aid and opportunities to individuals and communities based on socioeconomic indicators rather than race.

Poverty does not wear a racial face; it cuts across all groups. By shifting the basis of support from race to need, Malaysia could address inequality more effectively while reducing resentment and division.

Another approach would be to limit the use of race and religion data to national censuses or research contexts, rather than embedding them in every school or scholarship application.

This would allow the state to monitor demographic trends without perpetuating discrimination in everyday governance.

Hari Malaysia and the unfinished question of belonging

Hari Malaysia is supposed to celebrate unity in diversity. Yet the persistence of race and religion boxes on our forms reminds us how far we are from that aspiration.

To tick a box is to be reminded that the state sees us not first as Malaysians, but as Malay, Chinese, Indian, Iban, Kadazan, or “Others.”

It is to be reminded that belonging is mediated through categories, rather than embraced as unconditional citizenship.

The unfinished work of Malaysia is not only about economic development or political reform. It is about dismantling the invisible structures that divide us daily, and none is more symbolic than the boxes we continue to tick.

To move forward, Malaysia must dare to imagine a future where forms ask not what race or religion we are, but what dreams and skills we bring.

Where opportunities are not distributed according to identity but according to need and merit. Where citizenship itself is not conditional, but fully shared.

Until then, each time we fill in a form, we are reminded of the gap between the Malaysia we live in and the Malaysia we aspire to.

The challenge before us is simple yet profound: can we, as a nation, learn to see each other beyond the boxes?

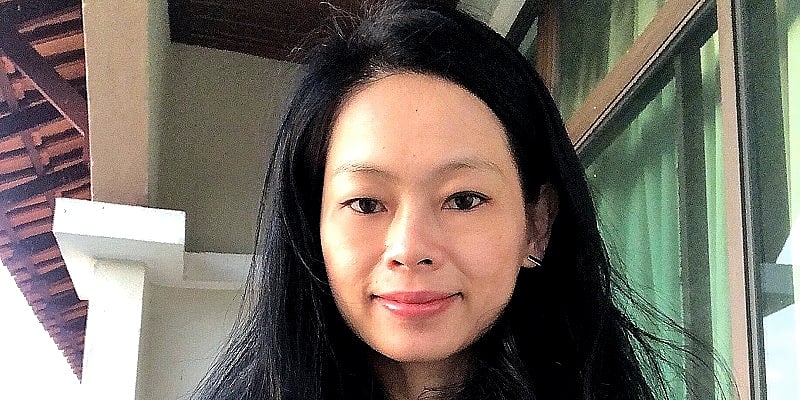

(Khoo Ying Hooi, PhD, is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Human Rights at Universiti Malaya. Her work spans human rights research, diplomacy, and policy engagement across ASEAN and Timor-Leste, along with active contributions in editorial and advisory capacities.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT