Many years ago, by chance, I stumbled upon a 1958 history textbook titled “The Malayan Story” written by Philip N. Nazareth and illustrated by K.S. Wee.

Leaving aside the background of these two men, what fascinated me most was actually the preface and the table of contents.

The preface was written in 1956 by David Marshall, then Chief Minister of Singapore, and Tunku Abdul Rahman, Chief Minister of the Federation of Malaya.

In his words, Tunku pointed out:

“At a time when Malaya is about to achieve independence, the publication of The Malayan Story is most timely. Young people should understand the history and background of their own country, rather than only focus on faraway places.

“Yet such works have been rare in the past, and if we do not work to fill the gap, our children will remain ignorant of their homeland and lack pride in it.”

I then noticed in the table of contents that Chapter 3 was titled “The Aborigines of Malaya: The Negritos, The Senoi, and The Aboriginal Malays.”

Although it spanned only four pages, the author still managed to describe in simple language with vivid illustrations the physical traits, geographical distribution, and livelihoods of these early inhabitants.

As the Father of Malaysia, Tunku Abdul Rahman clearly supported the inclusion of indigenous history in school textbooks.

Yet, 68 years after independence and 62 years after the formation of Malaysia, who tore out this crucial chapter, leaving our children unable to hear the voices of the indigenous peoples, or even know of their existence?

In fact, every August is not only the Independence month for Malaysia but also an important moment of celebration for the indigenous peoples of Malaysia.

On 9 August 1982, the UN Working Group on Indigenous Populations convened its first meeting in Geneva, marking the first large-scale, formal participation of indigenous people in the UN human rights system.

In 1994, the UN designated this day as the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, translated locally as Hari Orang Asal Sedunia.

Although the UN has yet to adopt a strict, unified definition of “indigenous peoples,” the Martinez Cobo Report and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) note four key traits: historical continuity with pre-colonial societies, self-identification as distinct from other groups, unique socio-economic and cultural systems, and a non-dominant position in contemporary society.

Indigenous peoples also want a ‘new year’

I first learned about forgotten International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples in 2018—which also marked the beginning of my serious engagement with the indigenous communities of Peninsular Malaysia.

With no connections at that time, I would drive long distances to attend any event related to them, just to build ties with these people who live deep inland and rarely interact with outsiders.

In my first year attending a celebration in Selangor, I bought a book on the Batek people by American anthropologists the Endicotts. That later became the starting point of my investigative reporting on the deaths of 16 Batek people — work that was eventually shortlisted for the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) Award for Excellence in Human Rights Reporting.

The following year, at the same festival again, I met Mahat China, a Semai writer who writes under the pen name Akiya.

I later wrote a piece based on him, which won a Global Chinese Literary Award.

Awards aside, my true wish was to bring indigenous voices into the Chinese-speaking world, so that more young people could recognize their existence.

Without the indigenous peoples, our understanding of Malaysia will always be incomplete and fragmented.

Last year, I celebrated the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples in Johor. To my surprise, the Urang Huluk (upstream people) of Endau-Rompin National Park celebrated the day as their own New Year (raya).

They told me: “Malays, Chinese, and Indians all have their New Years. There is no reason the indigenous peoples shouldn’t have one.

“After all, we are the first inhabitants of this land!”

Interestingly, this reinvented “traditional festival” mirrors other cultures in many ways.

During their “New Year,” the Urang Huluk make their own cassava cakes (lepet) and also wrap ketupat like the Malays.

Since August coincides with the seventh lunar month, some perform ancestor worship or burn paper offerings like the Chinese.

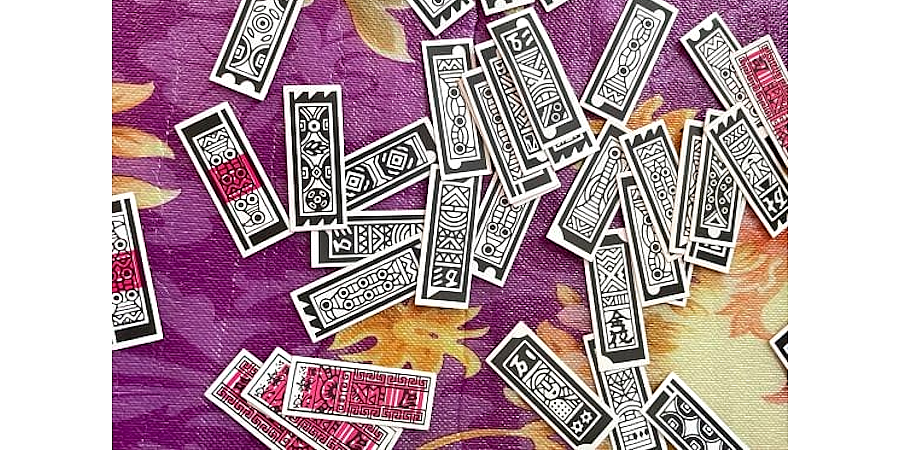

To my amazement, they also enjoy playing a card game once popular in Peranakan society—Daun Ceki.

At first, I knew nothing about Daun Ceki, and the Chinese characters printed on the cards left me puzzled.

When I casually asked a woman about the game’s origins, her answer shocked and delighted me:

“This was a game your Chinese ancestors taught our ancestors. Now you no longer play it, but we indigenous people have preserved it for you.”

So, when I returned this year, my first task was to learn how to play Daun Ceki.

In their context, the cards with Chinese characters had been given new names.

Nobody could explain the logic behind them, but the very existence of this game proves that cross-cultural exchange in Malaysia has never ceased.

‘Tumpang’ others’ festivals to celebrate

My senior, Ng Jia Han, is an expert on the mixed-heritage Sino-indigenous communities of Sabah.

I used to assume that such hybrid identities existed only in East Malaysia, but I have in recent years repeatedly encountered very complex ancestries among Peninsular indigenous peoples—often impossible to sum up in a single racial label.

Sometimes, my interviewees describe themselves this way:

“I have Semai heritage, so I celebrate Christmas in Perak.

“I also have Temuan and Chinese heritage, so I celebrate Lunar New Year in Negeri Sembilan.

“I also have Urang Huluk heritage, so I celebrate the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples in Johor.”

Others, however, sigh and say they can only tumpang (piggyback) on other ethnic groups’ holidays to celebrate their own festivals, since the government of Malaysia has never declared the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples a public holiday.

According to Ng ’s research, the first prime minister to have issued an official greeting on the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples was Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob, possibly because of his relatively weak political position and the significant number of indigenous voters in his constituency of Bera.

The second was current Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim, who greeted them via his official Facebook page.

In contrast, other former prime ministers with official social media accounts such as Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Datuk Seri Najib Tun Razak—have never extended greetings on this day.

At the end of one such celebration, after the feast was over, one of my interviewees whispered to me:

“I really hope that one day, our raya (the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples) can be made a national holiday, just like the Malays, Chinese, and Indians have for their festivals.”

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT