I often hear all kinds of mythical stories whenever I wander through the forest. Some warn humans to beware of demons and spirits, while others praise the protection of ancestral spirits and deities.

However, in the world of the indigenous people, there is one figure that is both good and evil. It is believed to devour human souls while also being the guardian of forest.

This controversial “creature” has many names. In North America, it is called Bigfoot or Sasquatch; in the Himalayas, it is known as the Yeti; and in Malaysia, one of its names is Mawas.

Yes, it is the mysterious, unproven creature that frequently appears in world mythology—Bigfoot. Records about Mawas are scarce, with the earliest documents tracing back to the British colonial era.

At that time, explorers heard stories from indigenous people about encounters with Mawas deep in the Peninsular Malaysia.

These accounts often describe it as a creature standing six to 10 feet tall, covered in long black or reddish fur, resembling an ape, and possess supernatural abilities that allow it to move swiftly through the forest.

But where has Mawas been sighted? According to a 2005 report, three workers reported seeing three Bigfoot-like creatures near the indigenous village of Mawai in Kota Tinggi, Johor.

Later, massive human-like footprints were discovered nearby, with one measuring up to 45 centimetres long, causing a sensation both locally and internationally.

The following year, the Johor state government even formed a forest expedition team to verify the existence of Mawas – Malaysia’s first official search for a mythical creature.

Mawas enters children’s theatre

Regardless of whether the Johor government ultimately found Mawas, I recently had my own “encounter” with one! But instead of being in the south, it was in Selangor.

A few months ago, I was invited by Shaq Koyok, an indigenous artist from the Temuan tribe, to visit his village and witness this legendary Mawas.

To my surprise, its appearance was adorable and amusing – completely different from what historical records describe.

In reality, it was part of a cross-disciplinary art project called “Awas Mawas” (Beware of Bigfoot).

The initiative was led by sculptor William Koong, visual artist Forest Wong, theatre director Ayam Fared, community art advocate Fairuz Sulaiman, and performing artist Malin Faisal, with support from Orang Orang Drum Theatre.

Inspired by the Bread and Puppet Theatre in the United States, this artistic group spent three weeks in Temuan and Mah Meri villages, discussing myths and land issues with the locals.

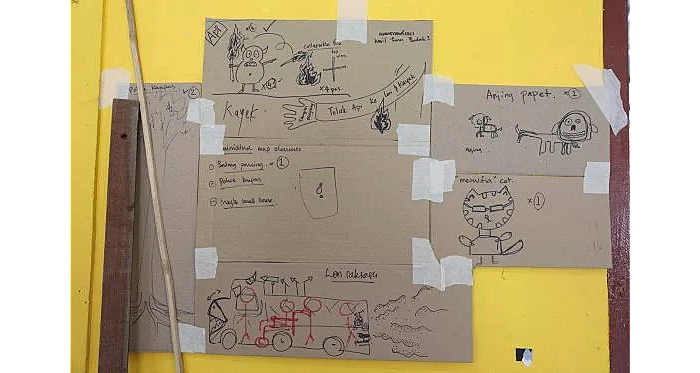

During this time, they encouraged children to create their own stories and characters, incorporating adult perspectives, and then worked together to craft giant puppets using eco-friendly materials like cardboard, dried leaves, and bamboo strips.

Among these were Mawas, the Temuan ancestral spirit Moyang Lanjut, and the Mah Meri ancestral spirit Moyang Tok Naning.

At the event’s finale, this “modern-day Mawas” acted as the narrator, leading the entire village in a cultural parade, while the children performed two different theatrical plays.

These plays aimed to empower them through art and help the public understand the collective struggles of indigenous communities.

For instance, in the Temuan tribe’s play, the story takes place when villagers are asleep. A group of cannibalistic monsters called Kayek drive a giant truck beast (Lori Raksasa) to steal their land.

The next day, negotiations with the Kayek fail, and in retaliation, they set fire to the forest. Desperate, the villagers perform the Hentak Balai ritual to summon Moyang Lanjut for help, ultimately succeeding in protecting their homeland.

The Mah Meri tribe’s story revolves around palm oil plantations. It follows a young boy who embarks on a journey to find nyireh batu wood so that his grandfather can carve ancestral masks.

Along the way, he encounters a group of sorrowful crabs and snails, who reveal that this type of tree no longer exists. Just then, Moyang Tok Naning appears and advises them that only by reviving the mangrove forests can they overcome their predicament.

Due to an irreparable conflict with the palm oil industry and being provoked by its representatives, the villagers and a giant snail bravely crash through the fortified walls, allowing seawater to flood the coastline and drown the commercial crops – eventually bring the mangroves back to life.

Indigenous children protest on Kuala Lumpur streets

Perhaps due to the overwhelming response to this art project, the Awas Mawas team brought their indigenous mythical characters to the streets of Kuala Lumpur in February this year, allowing urban dwellers to connect with the stories of marginalised communities.

Unfortunately, the weather was bad. Before the parade could begin, a heavy downpour forced organisers to adjust the event’s route.

As the members of Orang Orang Drum Theatre struck powerful drumbeats, the initially discouraged children once again lifted their props, continuously chanting “Awas Mawas” as they marched proudly through the Golden Triangle in Kuala Lumpur, capturing the attention of passers-by.

The only exception was the giant puppets, which had to be transported directly to the Berjaya Times Square for the final performance.

That day, I stood among the crowd, holding my camera, feeling somewhat overwhelmed.

First, the torrential rain made it extremely difficult to snap photographs. Second, Kuala Lumpur’s pedestrian environment is a nightmare – practically a “hell for walkers.”

Even with enforcement officers helping to clear the way, I worried that the two Moyang puppets might fall apart before reaching their destination.

Since its independence, the urban planning in Malaysia has been car-centric, with frequent development projects which lack in overall consideration, making it dangerous for pedestrians to cross the streets.

This exclusionary approach to city-building made me wonder – has it also suppressed the emergence of social movements? After all, when simply walking on the streets is an obstacle, how can people protest? How can they voice their concerns?

Of course, protests don’t always have to involve flag-waving or violent clashes. When these indigenous children bravely took to the streets, what I saw was an awakening of strength.

In this concrete jungle, their fragile “cardboard land” may have seemed insignificant, even soaked by the rain, but together, these pieces formed a powerful critique of capitalism.

Curiously, in my past experiences, many indigenous rituals began with rain and ended with sunshine – and this time was no exception.

It was as if the ancestral spirits were silently walking alongside the children, joining them in their march.

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes From the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT