The first time I visited Endau-Rompin National Park in Johor, I was quite surprised.

Many young children there speak Mandarin. They either watched TV series from China or sang “Twinkle, twinkle little star” in Chinese.

When I probed further, I realized many of them studied in Chinese primary schools.

Some of the adults had darker skin but displayed Chinese features or carried hidden Chinese surnames—mixed-heritage individuals from inter-marriages between the indigenous Urang Huluk and the Chinese.

One person who impressed me was a woman named Shaffila. She was same age as me.

When she tried to write her Chinese name in my field notebook, she suddenly paused, unable to remember how to write one of the characters. So, I took the pen from her and finished the remaining strokes.

Shaffila shared that she used to attend a Chinese primary school where she was the only Orang Asli (indigenous) pupil in her class.

Whenever her Chinese classmates asked about her race, she could only respond with “Orang Asli,” because whether it was the official name “Jakun” or the term they identified with more, Urang Huluk, most Malaysians had never heard of them, making it hard to explain.

Later, when she was studying Malay Literature at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), she finally met a professor familiar with indigenous people.

When she said she was a Jakun, the professor even asked whether she was from Johor or Pahang. She was overjoyed that someone finally recognized her identity and origin.

However, for Urang Huluk, acknowledging themselves as “Jakun” is a complicated process.

Since the 19th century, when “racial science” was invented, the term carried negative connotations like “stupid,” “backward,” and “ignorant.” In British colonial records, “Jakun” was often used to describe “savage Malays.”

Jakun: A name or a joke?

Once, a Malay neighbor asked me which group of Orang Asli I was studying. Hesitating, I replied, “The Jakun of Johor.”

Unexpectedly, they burst into laughter. They explained that “Jakun” is used in everyday Malay slang to describe joke—they couldn’t believe it was actually the name of an ethnic group.

So, what kind of joke is it? It’s like how when I studied in Taiwan, the cashiers would ask, “Do you need a carrier?” (meaning an app to store e-receipts), and I was totally confused. Later I realized what they meant and laughed at myself for being such a “country bumpkin.”

Similarly, in Malay, there’s a saying “rusa masuk ke kampung” (a deer entering the village), meaning someone is shocked or awed by something new.

People often follow it with “macam Jakun” or “jadi Jakun,” implying someone is naïve or ignorant—just like a Jakun.

Although the true origin of “Jakun” remains unclear, the earliest known usage can be traced back to the 1830s in Hikayat Abdullah by Munshi Abdullah. He described the Jakun people as having “animal-like habits,” a “language like birds quarreling,” and a “wild nature.”

Early British administrators adopted the Malay term “Jakun” to refer broadly to indigenous peoples of the southern Malay Peninsula.

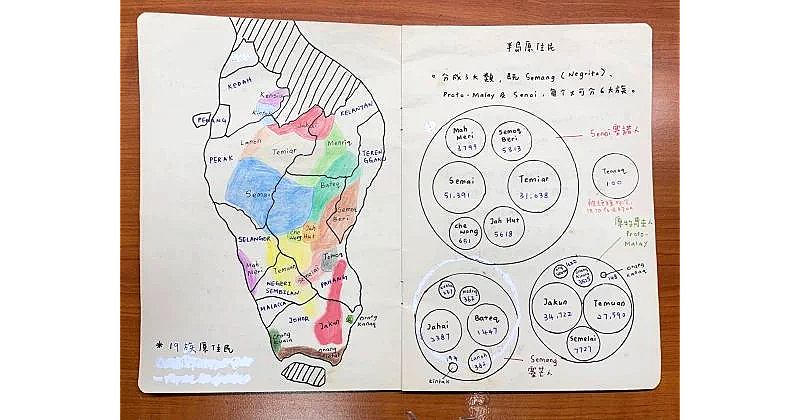

Over time, it became the name of a specific group and was categorized alongside Temuan, Semelai, Orang Kuala, Orang Seletar, and Orang Kanaq under the label Proto-Malay sub-group.

The term “Proto” here, influenced by evolutionist thinking, is meant to contrast with the more “modern” Deutero-Malay. Clearly influenced by the theory of evolution, but not an accurate definition.

According to the dictionary published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, “Jakun” refers to the Proto-Malay people living in the forests of Pahang, Johor and Negeri Sembilan, without any negative connotations—showing that the “joke” is informal and unofficial.

From my experience, the Jakun of Pahang seem relatively accepting of the term, but the Jakun of Johor—or more accurately, Urang Huluk—consider it a malicious misnomer.

Sakai: Friend or slave?

Interestingly, I found that the Chinese are even more familiar with the term “Sakai.”

Many elders, upon hearing that I was studying the Orang Asli, didn’t use “Jakun” or the Taiwanese term “yuan zhu min” (indigenous people). Instead, they called them “Sakai,” “mountain savages” (shan fan), or “barbarians” (huan na)—terms that made me frown.

Compared to the term “Jakun,” “Sakai” carries negative baggage, including associations with slavery.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, slavery was widespread on the Malay Peninsula, and many northern and central indigenous people were enslaved. These painful ancestral experiences are still preserved in oral histories and folklore.

According to Canadian anthropologist Couillard, the word “Sakai” originates from the Sanskrit word “sakhi,” meaning “friend.”

Around the 7th century, Indian traders used it to refer to trading partners.

A Semai author, Akiya, told me that in his language, “Sakai” also means “cooperation.” He speculates that because the indigenous peoples value symbiosis and mutual aid, they used the word so often that it eventually became their label.

Before independence, many government documents used “Sakai” as the “nationality” (in the older sense of ethnicity) for Orang Asli, and even early legal documents for indigenous reserves used the term “Sakai reservations.”

Although “Sakai,” with its connotations of slavery, has now been abandoned officially, it’s still widely used among the public due to a lack of historical understanding.

The term “Senoi” has replaced it now. This word, from various Aslian languages of the South Aslian branches of the Austro-asiatic language family and means “human being” and generally refers to groups like Semai, Temiar, Mah Meri, Jah Hut, Semaq Beri, and Che Wong.

Malays who fish vs. Chinese using chopsticks

Of course, interactions between ethnic groups have never been one-way. The Orang Asli also have nicknames for “others.” For instance, Malays are often called “gop” or “jobok.” A Jah Hut friend told me that “gop” means “fish-scooping,” because Malay prayer gestures reminded them of that motion. “Jobok,” from Mah Meri language, is related to “Indonesia.” Interestingly, these terms are used as shared lingo among Orang Asli groups.

And the Chinese? My Mah Meri friend laughed and said, “We call you chongke.” When I learned that chongke means “chopsticks,” I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. But I did learn to introduce myself with a bit of self-mockery:

“Gelar e’ et Yi Ke, e’ et chong ke” (“I’m Yi Ke, I’m chopsticks.”)

I thought—ah, these friends from the forests, they’re still far kinder to us than we’ve been to them!

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT