As city dwellers, we have long been accustomed to using mobile phones to complete various tasks, such as contacting others, writing emails, and scheduling appointments.

If we need to meet with someone from another country, we don’t necessarily have to fly there in person, as modern technology has made it possible to overcome both distance and time constraints.

However, for most of the indigenous people, this kind of convenience remains a luxury. Even though we all live in the same country, their CelcomDigi signal might just happen to be “out of service” in the forest; U Mobile might become “immobile” in remote villages; and Maxis, more often than not, might as well be renamed “No Signal” – even climbing a tree to get a better reception doesn’t guarantee the ability to make a simple phone call!

Aminah is one of the few indigenous people who not only own a mobile phone but also have network access.

She is also a customary leader. Since she is easier to contact than the others, I optimistically assumed that any discussions we needed would be settled quickly.

On a hot Sunday afternoon, Aminah and I arranged to meet at a hotel in Kuala Lumpur.

I have always been punctual – once my schedule is set, I immediately note it down in my calendar and make sure to arrive at least 30 minutes early to avoid keeping anyone waiting.

However, upon arriving at the hotel’s front desk, I was met with an unexpected piece of news:

“There was indeed a group of indigenous people holding a meeting here today, but they checked out at noon.”

Checked out? I glanced at my watch – it was 5 p.m. My meeting with Aminah was scheduled for 5.30 p.m. Where was she?

After thanking the receptionist, I walked to the hotel lobby and called Aminah.

Though I had a nagging feeling that I was about to be stood up, I remained calm and politely inquired about her whereabouts. To my surprise, Aminah nonchalantly replied, “My meeting ended early, and it was too hot, so I went home.”

Hearing this response, I was both amused and annoyed – what kind of excuse was that for missing an appointment?

As I pondered my next move, Aminah casually suggested: “Why don’t you just come to my village instead?”

I had originally hoped to save time by meeting Aminah in the city, but in the end, I had no choice but to venture into the forest just to have a proper conversation with her.

The last mile to the indigenous village: an immeasurable distance

Unable to contain my impatience, I set off early the next morning, driving alone to Aminah’s village – a place that even satellite navigation couldn’t locate.

This time, I forced myself to go to bed early, downed a cup of coffee before setting out at dawn, and convinced myself that with enough sleep and caffeine, I could make it through the journey.

After a three-hour drive, I arrived at a small town and met Aminah in front of a convenience store. I immediately asked, “How long does it take to get from here to your village?”

Meeting Aminah for the first time, I was surprised by her petite frame – she looked like a young girl, and I had to bend slightly to speak with her.

It was hard to believe that she was already a grandmother.

Climbing into the passenger seat, she playfully replied, “That depends on your driving skill.”

Having visited several indigenous villages before, I thought I had already encountered the worst road conditions. But as I followed Aminah, my human GPS, onto a dirt road filled with sharp rocks and thick mud, I quickly realised that this was an entirely new level of challenge.

The road was in such a terrible state that I could only drive at a sluggish 20 km/h, inching along like a lumbering tortoise.

Every few meters, the car would get stuck in gravel or sink into a muddy pothole, requiring me to floor the accelerator to escape.

At one point, my brakes even failed, sending the car sliding from one slope into another ditch.

As dust and yellow sand swirled in the air, covering my car in a thick layer, I momentarily felt like I had entered the Sahara Desert. It wasn’t until I wiped my windshield clean that I realised the shadows I had mistaken for a caravan of camels were actually a long line of fully loaded logging trucks and palm oil lorries.

When the tenth truck passed by, I couldn’t help but ask again, “At this speed, when exactly are we going to reach your village?”

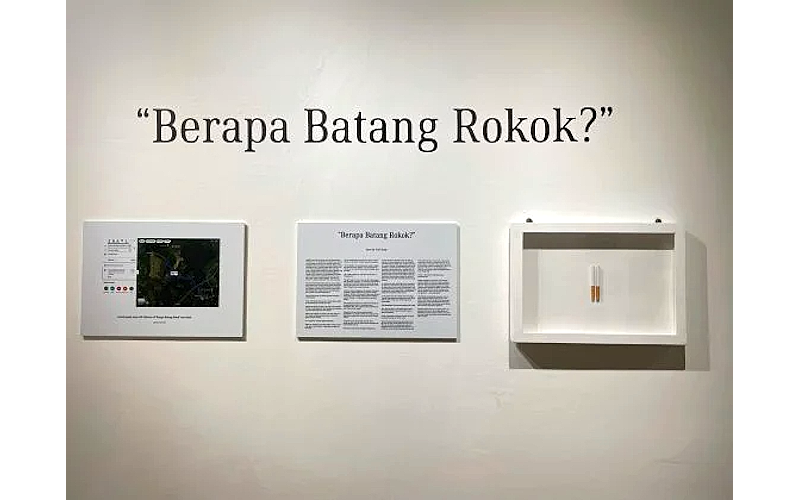

To my surprise, Aminah gave me an intriguing response: “About two cigarettes’ time (dua batang rokok)!”

An unconventional time measurement and a humorous protest

Two cigarettes’ time? As someone who has never smoked, I had no idea what that meant in minutes or seconds.

When I pressed for clarification, Aminah didn’t give me a direct answer but instead shared a story:

“Many years ago, the state government tried to take our land, and the case even went to the court.

“When my elderly mother was summoned to testify, the defendant’s lawyer asked her the same question: ‘How long does it take to get from town to your village?’

“My mother needed to prove that our people had lived on this land for generations and were familiar with the area. If she gave the wrong time or distance, we could have lost the case.

“But my mother was a village woman who had never been to school. Do you think she could have said ‘one hour’ or ‘15 kilometres’? Of course not. So, after thinking for a moment, she simply said, ‘Two cigarettes’ time’.”

Curious, I asked, “Did the lawyer understand what she meant?”

Aminah laughed. “Of course not! He looked completely confused and even asked my mother to explain. But the judge interrupted him and told him, ‘Why don’t you try driving from Kuala Lumpur to our village, count how many cigarettes you smoke along the way, and then divide by the time it takes? That way, you’ll understand how long one cigarette lasts, and how long two cigarettes take!’”

By the time Aminah finished her story, we had finally arrived at her remote village. Yet, I still couldn’t shake my curiosity about the “two cigarettes” measurement.

Glancing at my watch and estimating the time, I couldn’t help but joke, “This trip felt more like an entire pack of cigarettes!”

Aminah playfully mimed holding an invisible cigarette in the air, making exaggerated gestures as she explained: “When we say ‘two cigarettes’, we don’t mean smoking continuously – puff, puff, puff, non-stop.

“You take one puff, exhale, pause for a moment, take another puff, exhale again, rest a while, and repeat.”

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT