Winter in Taipei is always unpredictable. When it rains, it reminds me of a phrase that often appears in English novels: “chilled to the bone.”

Every day, I long for that land where summer lasts all year round.

By the time I arrived at Kuala Lumpur International Airport, it was already midnight.

My flight, originally scheduled to land at 8 pm, was delayed for four hours due to engine failure, filling the departure lounge with constant sighs and complaints.

Given the frequent plane crashes in recent times, every time I fly over an ocean, it feels like I’m gambling with fate.

Before turning off my phone, I’ve developed a habit of telling my family, “I love you,” afraid that I might never get another chance to express myself.

When the flight attendant announced in Malay, “Kepada warganegara, selamat pulang ke tanahair…” (To our citizens, welcome home…), the anxiety that had gripped me all day finally eased, and I told myself, “I’m home.”

As I stepped out of the cabin, a wave of warmth hit me that I had to take off my thick jacket as I walked towards the immigration hall.

Along the way, I noticed numerous posters promoting tourism in Malaysia.

There were images showcasing cultural performances of the Malays, Chinese, and Indians, as well as staged photos of Sabah’s Kadazan-Dusun people in the tropical rainforest, and Sarawak’s Ibans smiling in front of their longhouses – perfectly embodying Malaysia’s “Truly Asia” spirit.

However, I quickly realised something – why is there not a single photo of the Temuan people, despite this airport being the gateway to Malaysia, welcoming travellers from around the world?

The Temuan people once called this place home

The reason I bring up the Temuan people here is that before Kuala Lumpur International Airport was built, the site was once their homeland.

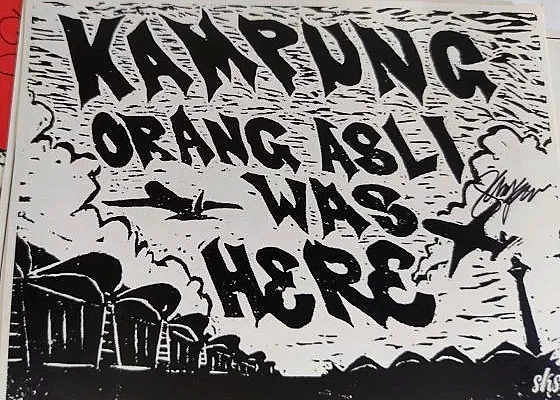

To build the airport, the government forcibly relocated the indigenous people at Kampung Orang Asli Busut and Kampung Orang Asli Air Hitam, merging them into a new settlement in Kuala Langat, renamed Kampung Orang Asli Busut Baru in 1993.

They were ultimately forced to accept the arrangement despite their silent protest. However, the graves of their ancestors remain buried beneath the airport’s soil to this day.

Because of this, the Temuan people often joke privately, calling the airport a “ghost place” (tempat hantu).

For most Malaysians, the airport is a gateway to the world and the first stop when returning home. But for the Temuan people, their home was sealed beneath steel and concrete. They could no longer visit their ancestors.

Temuan cultural exhibition hosted by New Era students

Temuan’s traditional beliefs share similarities with Chinese customs.

Many villages celebrate “Haik Muyang”, a day dedicated to honouring their ancestors and expressing gratitude for their blessings and protection in December.

A group of media and communication students from New Era University College hosted the “Ruang Temuan” cultural exhibition at Papan Haus in Petaling Jaya on 10 January in collaboration with the Global Environment Centre (GEC), the Friends of the Temuan Indigenous People Association (SGAT), and Temuan artist Shaq Koyok,

Through art installations and images, the exhibition showcased Haik Muyang, traditional Temuan attire, and handicraft.

There was also a display of artworks created by indigenous children, illustrating their perception of home in a whimsical, innocent style.

The exhibition cleverly borrowed the concept of “Ruang Tamu” (living room), creating a space where all Malaysians were invited to be “guests” and connect with the Temuan people – listening to the voices and stories of this marginalised community.

On the opening day, every visitor received a tanjak, a traditional headpiece woven with mengkuang leaves.

Upon wearing it, one would feel transported into a sacred space.

In a dimly lit room, a sangga (small shrine placed at the entrance of Temuan homes) came to life through projections. Faintly visible were ancestral offerings – white candles, drinks, biscuits, and glutinous rice cakes.

Thick white smoke filled the air when a button is pressed, simulating the burning of kemenyan (benzoin resin) in their ancestral rituals.

This immersive experience allowed visitors to feel a part of Haik Muyang, even if they never witnessed it before.

The importance of indigenous empowerment

My first indigenous friend is Shaq Koyok.

For this exhibition, the students conducted field research in Kampung Orang Asli Pulau Kempas and Kampung Orang Asli Broga. The former is Shaq’s home village, while the relocated settlement mentioned earlier is right next door.

Although I have known Shaq for six years, I rarely touch on Temuan-related topics – not because they are uninteresting, but because Shaq himself is a passionate and active advocate. He doesn’t need me to speak on his behalf.

The last time we met was at an online symposium on indigenous communities in Peninsular Malaysia.

Most of the speakers were Western anthropologists – veteran experts in their field. However, the four-hour discussion ended on a sour note.

Why? Because their research reports were cold and academic, filled with numbers and complex theories. There was no human connection, no real voices from the indigenous community.

Shaq, the only indigenous representative present, was frustrated and boldly criticised the research as “completely out of touch”, failing to bring any real benefits to the community.

At the exhibition, I brought up that incident again, praising his courage. I admitted that some battles can only be fought by the indigenous people themselves.

When New Zealand attempted to pass a bill that weakened Māori rights last year, a Māori politician, Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke, responded by performing the haka (traditional war dance) in Parliament, shocking the world.

Hearing this, Shaq made a wish: “I hope that one day, the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia can have that same strength.”

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT