Malaysia’s Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim has recently confirmed the nation’s interest in joining the BRICS group and its preparedness to undertake the necessary steps for membership.

The Foreign Ministry is evaluating Malaysia’s strategic approach to collaboration with the group, which is increasingly relevant among Global South nations.

While there is a discernible gap between intent and actual membership, this development is highly promising for our nation.

EMIR Research has persistently championed this cause, particularly since the reignition of what is becoming ever more obvious, the proxy hybrid colonial war by the collective West in Ukraine, in precise terms (refer to “Indo-Pacific democracy dynamics: impacts of the Ukrainian war on the global democratic order”), and similar absolutely barbaric colonisation attempt in the Middle East (“US-Israeli political exceptionalism must end”).

EMIR Research also has delineated working with BRICS as an important step towards “de-dollarisation”, as explored in its earlier publications “De-dollarisation: elbowing USD in a multipolar world” and “Petrodollar warfare: oil, Russia and the future of the Dollar”.

The trend is absolutely apparent now with the most recent global developments such as Saudi Arabia not renewing its 50-year petrodollar contract and opting for other currencies, China massively dumping US treasury bills, BRICS announcing their alternative payment system, and more countries signing bilateral trade deals.

De-dollarisation, however, should be seen as an integral part of a wider movement to disassociate from the US foreign policy, which is increasingly viewed as detrimental to sustained global harmony and peace.

There is a growing global awareness of a metaphorical sinking ship, and those who do not quickly distance themselves and adopt a more neutral and balanced stance may be drawn into the ensuing vortex.

The old global order—characterised by injustice, manipulation, unipolarity, and the artificially imposed dominance of a few currencies, which in turn centralises global political and economic power to serve the interests of a select few nations (so-called “developed” ones)—is evidently fracturing, along with its compromised financial platforms and mechanisms.

As this void emerges, it is crucial to establish an alternative foundation and a more responsible multipolar world based on mutually beneficial cooperation.

This is precisely what the BRICS group has been doing in the background since as early as 2006, when its founding member states held their first informal meeting at the United Nations summit in New York.

At that time, the nascent bloc included only Brazil, Russia, India and China, hence its acronym “BRIC”.

Noteworthy, BRICS is devoid of geopolitical underpinnings and should not be viewed as a counterpart to NATO and its ilk.

Illustrative of this is the fact that Turkey, a NATO member, has also expressed its desire to work with the BRICS, demonstrating diplomatic awareness of a proactive, balanced stance.

The absence of geopolitical underpinnings is aligned with the BRICS’ core philosophy of being the platform for mutually beneficial partnerships of ALL participating countries in a joint quest for solving pressing global and regional challenges.

In fact, the absence of clear geopolitical underpinnings (a balanced stance) is one of the key prerequisites of joining the club.

BRICS lacks the formalities of UN or NATO, with no set structure or leader.

Annual summits, led by rotating member states’ leaders, prioritise mutually beneficial economic, social, and trade advancements. Legalities stem from summit protocols and international agreements.

Despite its history, BRICS has yet to emerge as a collective entity on the international stage, and its member countries lack a unified stance on critical geopolitical issues, as demonstrated by the failure to agree on a joint declaration regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Moreover, BRICS applications are non-committal, allowing countries to withdraw or reverse their decision due to internal politics, exemplified by Argentina’s choice to align with the US under its new president shortly after its membership with BRICS was approved.

These “headwinds” are bound to persist for some time. This is entirely consistent with Tuckman’s theory on how a newly formed group transitions from “storming” to “performing”.

Also, understandably, global restructuring is a process that spans a substantial timeframe.

Nevertheless, the BRICS ship sails under full sail. Consistently advancing its agenda from summit to summit, BRICS introduces key initiatives for deeper integration within the bloc, offering significant benefits to collaborating countries, even without full membership.

For example, in its official founding year, 2009, the group sealed its commitment to jointly overcome the global food security crisis.

In 2014, the group initiated its own multilateral development bank (proposed in 2012) with a $100 billion reserve, offering local currency loans and membership beyond BRICS.

The Ufa Declaration 2015 charted a solid Action Plan for a shift within BRICS towards trade in national currencies. The implementation of the “Silk Road” Economic Belt strategy was also considered.

The year 2016 saw an MOU on the establishment of the BRICS Agricultural Research Platform. Also, the group mooted the idea of its own credit rating agency at some point in the future.

The idea of BRICS+ emerged in 2017, paving the way to permanent collaboration with BRICS allies beyond the original summit-to-summit “outreach”.

Contrary to common belief, BRICS may not benefit from increased full membership due to the potential increased risk of conflicts and decision-making delays. Hence, the group’s popularity has prompted the creation of a new “partners” category for ongoing collaboration, preserving the BRICS core and potentially innovating global relations—an exciting development to watch for its impact on a fairer international order.

In 2019, the BRICS ministers of science, technology, and innovation supported the proposals for developing the Global Research Advanced Infrastructure Network, including the BRICS Virtual Institute of Photonics and the BRICS Network Centre for Materials Science and Nanotechnology.

In 2023, BRICS considered creating a common cashless international settlement unit (currency) as an alternative to the US dollar, and financial token to bypass SWIFT.

Overall, collaboration with BRICS presents benefits well-suited to Malaysia’s current needs, as well as those of many other developing nations:

■ Access to an alternative, safer, and fairer banking system, where excess reserves would not be simply “written off” driven by the geopolitical interests of a select few.

■ Strengthening local currency due to access to trade and financing in local currency.

■ Access to high-value and non-oppressive Foreign Direct Investments.

■ Expanded access to the market where things of real value are exchanged for things of real value as opposed to the Western “bubble economy” where the air is traded for air. Those rushing to cooperate with BRICS are mainly representatives of the Global South–all are countries rich in natural resources and other globally demanded commodities and products, which raises an interesting question of whether the oft-quoted Figure 1 is a fair reflection of real economic power. Moreover, when comparing economies using purchasing power parity (PPP), which enables a more meaningful assessment of economic productivity across countries, the BRICS group overtook the G7 several years ago.

■ Access to platforms for fair exchange in terms of culture, science, and technology, free from political biases, fostering true collaboration and mutual growth.

Notably, the situation around “economic sanctions” has vividly demonstrated to the whole world that Western technologies and platforms can be as toxic as their currencies, and therefore, they should be subject to immediate diversification to protect national interests.

This is where BRICS offers a platform to work with nations that, when they enter foreign lands, create more than just multinational corporations (MNCs) seeking to exploit local economies.

They also establish universities and hubs for genuine knowledge transfer and collaboration, fostering the creation of entirely new industries and truly empowering local communities.

This is perhaps partly due to the deep scars left by Western colonialists in these countries, which they commonly share.

To sum it up succinctly, national sovereignty—the capacity to chart its own destiny, free from the influence of external and internal colonialists—may begin through collaboration with BRICS, an opportunity Malaysia certainly should not overlook.

Read also:

- Starmer’s ‘brick by brick’ only to be overwhelmed by BRICS+

- Navigating the BRICS storm: separating signal from noise

- Joining BRICS+: Anwar’s pragmatic and strategic choice for Malaysia

- Bridging horizons: Malaysia and BRICS unite for mutual prosperity

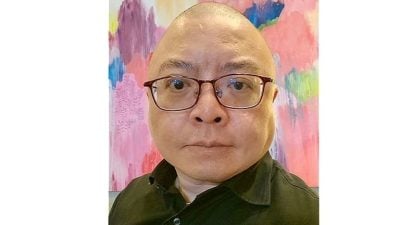

(Dr. Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT