Bank Negara Malaysia’s (BNM) latest update reveals the federal government’s direct debt has reached RM1.277 trillion, pushing the debt-to-GDP ratio to around 66 percent and breaching the 65 percent statutory ceiling.

Predictably, social media is lit up with politically charged claims.

Many simplistically argue that “Najib’s debt was safer,” citing lower ratios then. But they miss the real question: how much of that debt was simply hidden?

The real question isn’t just who borrowed or how much but how, why and what the rakyat got in return.

Focus should shift from what this government inherited to what must now be done to clean it up and who has the courage to act.

The headline debt figures are striking. But Malaysia’s most dangerous liabilities were never headline material—they were buried in the footnotes.

To compare fiscal prudence meaningfully, we must look beyond surface metrics.

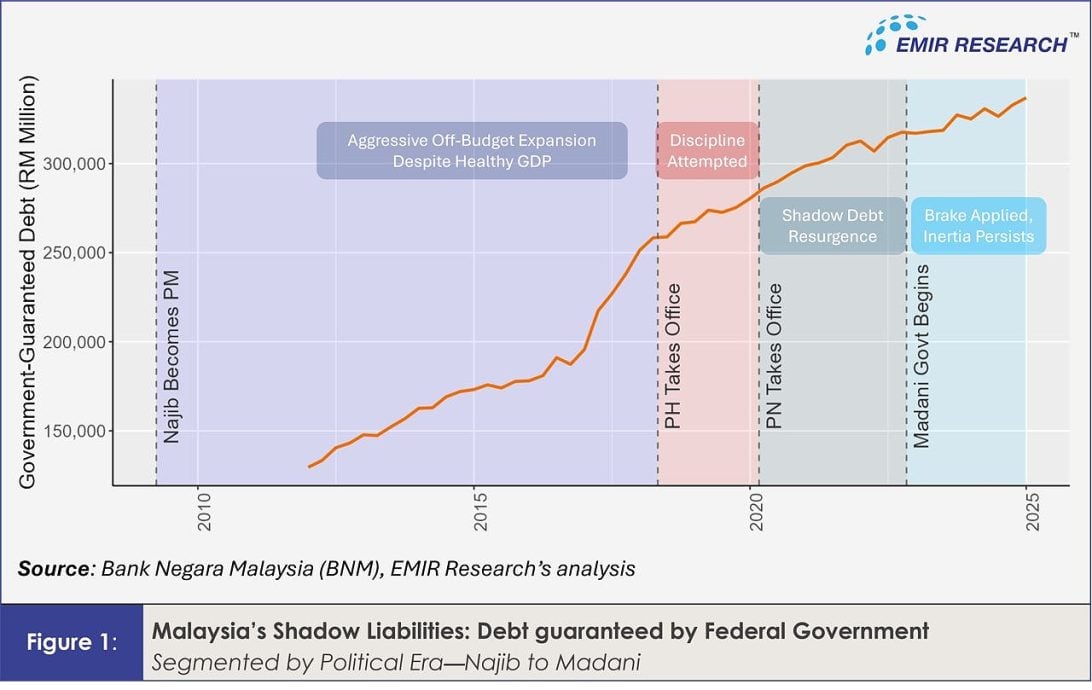

A full review of central government debt data from BNM, rather than cherry-picked quarterly ratios, reveals far more telling patterns (Figure 1).

From 2012 (the earliest available data point) to 2016, government-guaranteed debt rose steadily—off-budget borrowing kept off the official ledger.

After 2016, the pace accelerated significantly, aligning with the 1MDB scandal. Likely tools included Private Finance Initiatives (PFI), GLC obligations, and bond guarantees issued through Danajamin or MOF Inc.

This wasn’t prudence; it was debt outsourcing, removed from Parliament and public scrutiny.

The fact that it happened despite strong GDP growth highlights just how blatant the misuse had become.

During the Pakatan Harapan (PH) era, growth in government-guaranteed debt slowed noticeably, especially in the early period.

This suggests efforts were made to curb new guarantees, conduct audits, and restructure legacy obligations.

Despite political instability, PH managed to briefly pause the contingent debt spiral.

Under Perikatan Nasional (PN), the spiral resumed. Figure 1 shows a marked jump in guaranteed debt.

This cannot be pinned on Covid stimulus packages. Had those been properly budgeted, as they should have been, the rise clearly reflects continued Najib-era behavior: heavy use of off-budget guarantees to shield politically sensitive spending, including opaque GLCs, mega projects, or bailouts.

Consider Digital Nasional Berhad, which was marketed to the rakyat as neutral but financed like a sovereign liability with no voter scrutiny.

Under Madani government, growth in guaranteed debt halted, especially early on, reflecting a cautious approach amid tight fiscal constraints. But levels remain elevated and have begun rising again, albeit at a slower pace.

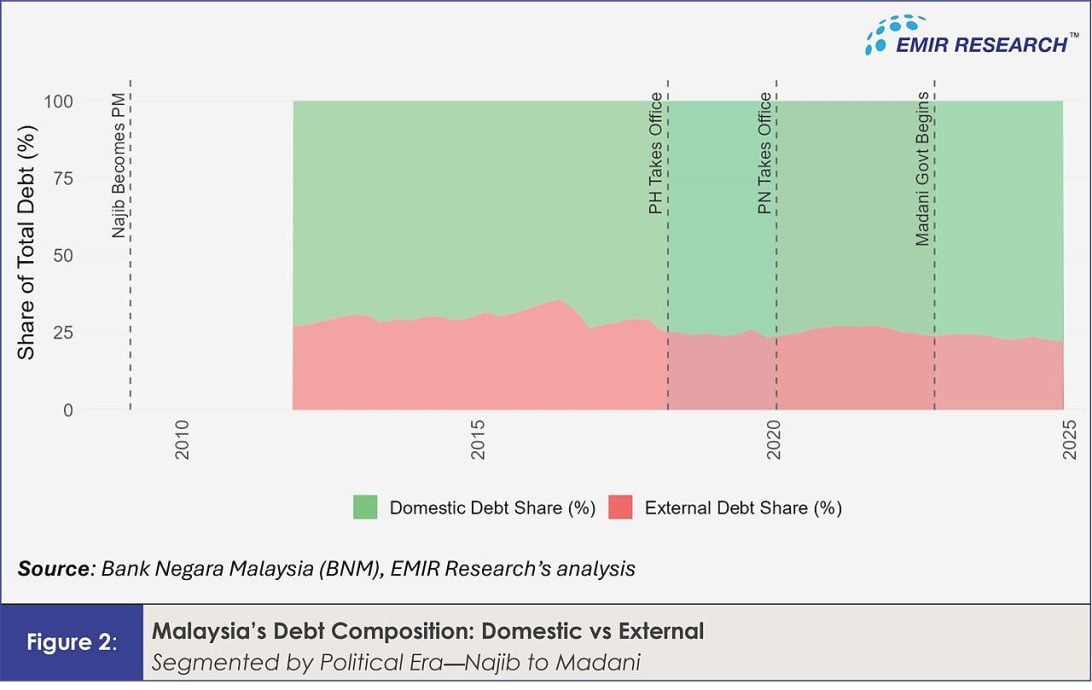

Debt composition (Figure 2) also tells a story. Under Najib, the external share rose steadily until 1MDB exposed the risks of opaque offshore financing.

PH managed to stabilize the trend. Under PN, it rose again noticeably.

The Madani government, by contrast, shows a clear retrenchment, suggesting a shift toward more transparent and accountable fiscal management.

On a side note, if the PN era shows the same clear pattern of structural abuse as BN, where does that lands their GE15 slogan: “We are like BN—but clean”?

Event under Madani government, while the brakes have clearly been applied, structural inertia persists. Some of the recent rise in guaranteed liabilities may well reflect debt inertia too—rollovers and restructuring of past obligations, including maturing PFI contracts, GLC bond servicing, or legacy refinancing.

In tight fiscal conditions, such tools become a fallback—not to expand the budget, but to keep inherited obligations afloat.

When fiscal space tightens, guarantees become the new deficit. That’s why Malaysia must shift from debt as motion to spending as impact. What we borrow matters less than what we deliver.

The Madani government has taken steps toward fiscal consolidation, including targeted subsidy reforms. These are necessary but technically more complex than other “low hanging” structural fixes.

While the intent to uphold fiscal prudence is visible, there remains ample room to do more.

At the vanguard of true fiscal reform lies one indispensable battle: the fight against corruption.

EMIR Research conservatively estimated that Malaysia lost around RM4.5 trillion to corruption and leakages between 1997 and 2022 (“Malaysia’s RM4.5 trillion losses to corruption, leakages: it’s time to TRAC”).

These losses include not only direct theft, but vast lost potential, magnified by the absence of any productivity-driven multiplier effect.

It is commendable that the government has announced the Accounting Fraud Task Force, echoing EMIR Research’s call for a Truth, Recovery and Amnesty Commission.

But to make real impact, the effort must go beyond symbolism: by demonstrating the will to pursue all offenders, including the well-connected; by recovering stolen assets at scale, not just issuing statements; and by embedding robust governance mechanisms to ensure accountability is structurally enforced, not politically negotiated.

Those who voluntarily return stolen assets—whether in the form of cash, property, or shares—could be granted limited amnesty and barred from future public roles.

Even those who are prosecuted and convicted may qualify if they fully restitute misappropriated funds.

The goal is not only justice but also meaningful recovery, both financially and institutionally.

Recovered assets could help reduce the deficit and fund high-impact national development.

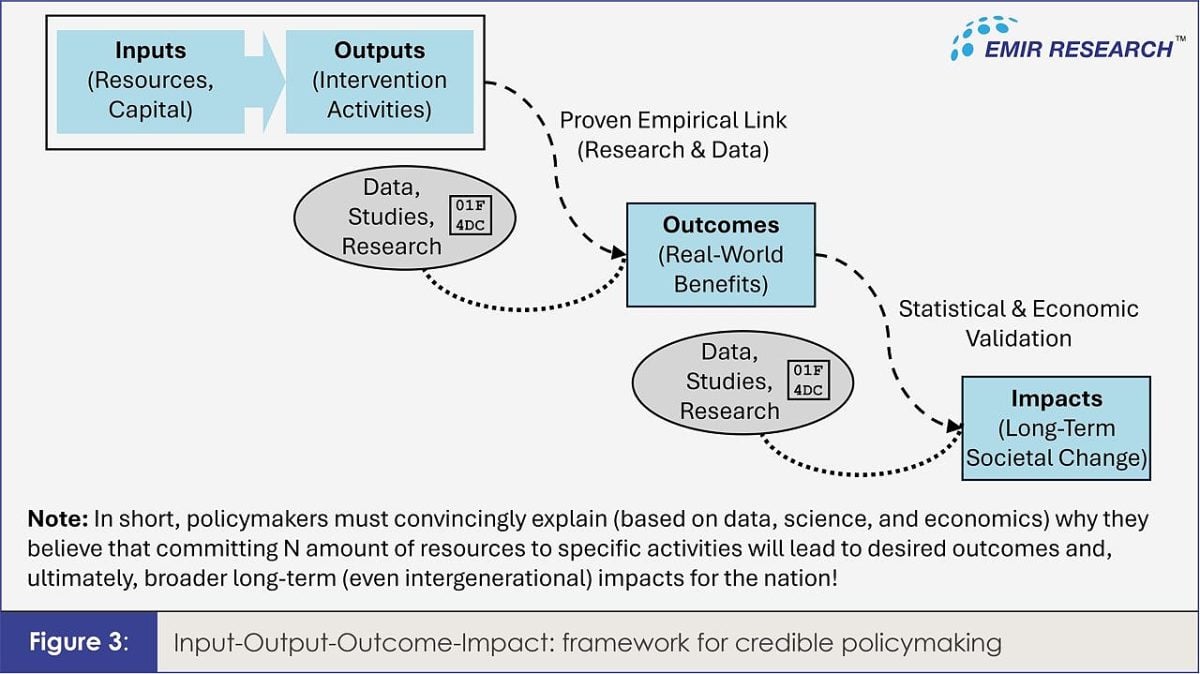

But productive use requires a clear guiding framework. The Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) model (Figure 3), which has long been championed by EMIR Research, must be institutionalized across ministries, agencies, GLCs, and bailout mechanisms (“Technocratic legal bailout framework to arrest “bailoutpreneurship’”).

The national budget itself ought to be grounded in IOOI principles (“Recalibrating national budget: eradicating leakages and corruption”).

This shift ensures every ringgit is accountable and delivers maximum tangible value: outcomes that improve lives and impacts that shape the nation’s future.

The government must prioritize high-impact sectors with strong multiplier effects and solid returns—generating revenue to narrow the fiscal gap.

These should be rooted in the real economy and powered by Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) technologies.

Innovation in these areas can cut out extractive middlemen, empower local producers, and build resilient income for ordinary Malaysians.

A prime example is food security. As shown in EMIR Research’s earlier report “4IR enabled farmers: Solving national food security,” equipping smallholders with tools like IoT irrigation, AI crop systems, and smart logistics can significantly boost productivity and incomes.

This lowers food prices, expands household spending, and stimulates demand across sectors, driving broader growth.

It also fuels demand for agri-tech and local tech talent, reinforcing a virtuous cycle of innovation, inclusion, and resilience.

However, truly unlocking such impacts depends on national scale-up, talent retention, and strong governance, especially dismantling all rent-seeking structures like exploitative aggregators and opaque deals.

This not only enables real economic transformation but also strengthens anti-corruption stance.

Additionally, GDP—often treated as the ultimate policy goal—is a flawed indicator. It counts cars sold, not time lost in traffic; fast food, not the burden of disease; extractive growth, not environmental loss.

It often measures activity, not actual value.

Real progress should be measured by how lives are improved, not just by the volume of goods and services sold.

Integrating IOOI metrics with a multidimensional wellbeing framework will help Malaysia budget not for image, but for lasting impact, including gradual fiscal deficit reduction as a natural consequence (see “Recalibrating national budget: Eradicating leakages and corruption”).

Finally, a more equitable Malaysia requires shifting from ethnic proxies to needs-based targeting, anchored in the IOOI framework and informed by better poverty metrics, including longitudinal surveys, vulnerability mapping, and qualitative tracking.

These tools reveal income mobility and distinguish between secure, vulnerable, and persistently poor, enabling sharper policy.

Crucially, this is not a rejection of Malays’ rightful place in national policy but a powerful reaffirmation.

As EMIR Research has shown, decades of the New Economic Policy (NEP) and its legacy tools have failed to uplift the poorest Malays, while only deepening intra-ethnic inequality and enabling elite capture (see “Ruthless colonization Mat Kilau could not even imagine”).

Replacing outdated mechanisms with transparent, data-driven support for structurally marginalized groups will better serve most Malays by addressing root causes of exclusion and thus fulfilling the NEP’s original spirit more effectively than the NEP itself ever did.

Publishing anonymized IOOI metrics and regular equity audits can help build public trust, especially among Malays, by making progress visible, accountable, and apolitical. It will also sharpen targeted reforms and better support transitions like subsidy removal.

In sum, the Madani government has a window of opportunity to do more than manage inherited debt—it can reform the ledger itself.

(Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT