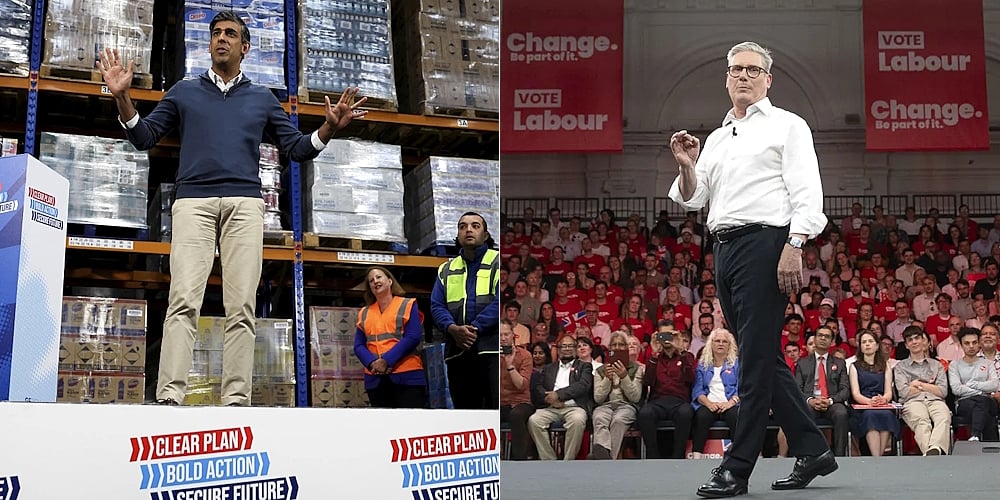

LONDON: Britain’s Labour Party headed for a landslide victory Friday in a parliamentary election, an exit poll suggested, as voters punished the governing Conservatives after 14 years of economic and political upheaval.

The poll released moments after voting closed indicated that centre-left Labour’s leader Keir Starmer will be the country’s next prime minister. He will face a jaded electorate impatient for change against a gloomy backdrop of economic malaise, mounting distrust in institutions and a fraying social fabric.

As the official count showed he won his seat in parliament, Starmer said voters “have spoken and they are ready for change.”

Thousands of electoral staff are tallying millions of ballot papers at counting centres across the country, while the Conservatives absorbed the shock of a historic defeat that would leave the depleted party in disarray and likely spark a contest to replace Prime Minister Rishi Sunak as leader.

“Nothing has gone well in the last 14 years,” said London voter James Erskine, who was optimistic for change in the hours before polls closed. “I just see this as the potential for a seismic shift, and that’s what I’m hoping for.”

While the suggested result appears to buck recent rightward electoral shifts in Europe, including in France and Italy, many of those same populist undercurrents flow in Britain. Reform UK leader Nigel Farage has roiled the race with his party’s anti-immigrant “take our country back” sentiment and undercut support for the Conservatives, who already faced dismal prospects.

Labour is on course to win about 410 seats in the 650-seat House of Commons and the Conservatives 131, according to the exit poll. That would be the fewest seats for the Tories in their nearly two-century history and would leave the party in disarray.

In a sign of the volatile public mood and anger at the system, some smaller parties appeared to have done well, including the centrist Liberal Democrats and Reform UK. A key unknown was whether Farage’s hard-right party could convert its success in grabbing attention into more than a handful of seats in Parliament.

Former Conservative leader William Hague said the poll indicated “a catastrophic result in historic terms for the Conservative Party.”

Still, Labour politicians, inured to years of disappointment, were cautious.

“The exit poll is encouraging, but obviously we don’t have any of the results yet,” deputy leader Angela Rayner told Sky News.

The poll is conducted by pollster Ipsos and asks people at scores of polling stations to fill out a replica ballot showing how they have voted. It usually provides a reliable though not exact projection of the outcome.

Britons vote on paper ballots, marking their choice in pencil, that are then counted by hand. Final results are expected by Friday morning.

Britain has experienced a run of turbulent years — some of it of the Conservatives’ own making and some of it not — that has left many voters pessimistic about their country’s future.

The U.K.’s exit from the European Union followed by the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine battered the economy, while lockdown-breaching parties held by then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his staff caused widespread anger.

Johnson’s successor, Liz Truss, rocked the economy further with a package of drastic tax cuts and lasted just 49 days in office. Rising poverty and cuts to state services have led to gripes about “Broken Britain.”

Hundreds of communities were locked in tight contests in which traditional party loyalties come second to more immediate concerns about the economy, crumbling infrastructure and the National Health Service.

In Henley-on-Thames, about 65 kilometres west of London, voters like Patricia Mulcahy, who is retired, sensed the nation was looking for something different. The community, which normally votes Conservative, may change its stripes this time.

“The younger generation are far more interested in change,’’ Mulcahy said. “So, I think whatever happens in Henley, in the country, there will be a big shift. But whoever gets in, they’ve got a heck of a job ahead of them. It’s not going to be easy.”

Anand Menon, professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs at King’s College London, said British voters were about to see a marked change in political atmosphere from the tumultuous “politics as pantomime” of the last few years.

“I think we’re going to have to get used again to relatively stable government, with ministers staying in power for quite a long time, and with government being able to think beyond the very short term to medium-term objectives,” he said.

In the first hour polls were open, Sunak made the short journey from his home to vote at Kirby Sigston Village Hall in northern England. He arrived with his wife, Akshata Murty, and walked hand-in-hand into the village hall, which is surrounded by rolling fields.

Hours later, Starmer walked with his wife, Victoria, into a polling place in north London to cast his vote.

Labour has not set pulses racing with its pledges to get the sluggish economy growing, invest in infrastructure and make Britain a “clean energy superpower.”

But nothing really went wrong in its campaign, either. The party has won the support of large chunks of the business community and endorsements from traditionally conservative newspapers, including the Rupert Murdoch-owned Sun tabloid, which praised Starmer for “dragging his party back to the centre ground of British politics.”

The Conservatives, meanwhile, have been plagued by gaffes. The campaign got off to an inauspicious start when rain drenched Sunak as he made the announcement outside 10 Downing St. Then, Sunak went home early from commemorations in France marking the 80th anniversary of the D-Day invasion.

Several Conservatives close to Sunak are being investigated over suspicions they used inside information to place bets on the date of the election before it was announced.

Sunak has struggled to shake off the taint of political chaos and mismanagement that’s gathered around the Conservatives.

But for many voters, the lack of trust applies not just to the governing party, but to politicians in general.

“I don’t know who’s for me as a working person,” said Michelle Bird, a port worker in Southampton on England’s south coast who was undecided about whether to vote Labour or Conservative in the days before the elections. “I don’t know whether it’s the devil you know or the devil you don’t.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT