MANILA: At least four people were killed in the restive southern Philippines on Monday as millions turned out to vote for village leaders following months of deadly poll-related violence.

Security forces were on high alert across the country for the long-delayed nationwide vote for more than 336,000 council positions.

While villages are the lowest-level government unit, the council posts are hotly contested because they are used by political parties to cultivate grassroots networks and build a support base for local and general elections.

More than 300,000 police officers and soldiers were deployed to secure polling stations in over 42,000 villages.

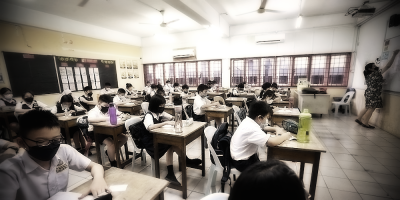

In the capital Manila, voters waited in long lines to cast their ballots at schools being used as polling venues.

“This is important for the people… we need to be able to consult someone over our problems,” said Rosemarie Garcia in the hardscrabble neighborhood of Tondo.

“We need somebody who is easily approachable to his or her constituents.”

Elections are a traditionally volatile time in the Philippines, which has lax gun laws and a violent political culture.

Commission on Elections chairman George Garcia said voting had been “generally peaceful” except for several incidents on the southern island of Mindanao.

Two people were killed and five others were wounded outside a polling station in Maguindanao del Norte province, police said.

The shootout happened during a confrontation between supporters of rival candidates for village captain, said Datu Odin Sinsuat municipality police chief Lieutenant-Colonel Esmail Madin.

In another incident on Mindanao, a woman was killed when a gunfight broke out after a van carrying a village captain and her supporters was stopped on a road by people backing her rival in Lanao del Norte province, the army said.

The husband of a village captain in Lanao del Sur province died after he was shot in the chest during a confrontation with his wife’s rival, police said.

In 2009, before it was divided into two provinces, Maguindanao was the scene of the country’s deadliest single incident of political violence on record.

Fifty-eight people were massacred as gunmen allegedly working for a local warlord attacked a group of people to stop a rival from filing his election candidacy.

‘Very important’ result

In the run-up to Monday’s vote, there were 30 confirmed incidents of election-related violence, compared with 35 in 2018, the Philippine National Police said Sunday, without providing an updated breakdown for the number of dead and injured.

About one-third of the incidents happened in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

Previous police data showed eight people were killed and seven injured in poll-related violence between August 28 and October 25.

More than 67 million people were registered to vote in the elections, which President Ferdinand Marcos described Monday as “very important” for higher-level politicians.

“What happens here in the barangay (village)… are going to have an effect on the results of the mid-term elections and subsequently at the national elections,” Marcos said after casting his vote in his family’s stronghold of Batac City in the northern province of Ilocos Norte.

“If other barangays tell you ‘I will deliver 350 votes for you in my barangay,’ rest assured you will get 350. That’s why the result is very important.”

Polling stations were due to close at 3:00 pm (0700 GMT), but voting was extended in some places.

Vote counting was underway and results would be announced late Monday, said Garcia.

Voters chose a village captain and seven councilors responsible for implementing national policies, resolving neighborhood disputes and providing basic public services.

Village councils also enable politicians to “disseminate funds and other favors to secure votes”, said Maria Ela Atienza, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines.

Village elections are supposed to be held every three years, but the last vote was in 2018.

They were postponed by former president Rodrigo Duterte and then his successor Marcos on the grounds the government could not afford them.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT