Strong consumer spending has supported growth in Asia’s three largest economies this year, but there are signs that the region’s recovery may be running out of steam.

We expect growth in Asia and the Pacific to accelerate from 3.9 percent in 2022 to 4.6 percent this year. This is largely explained by the post-reopening recovery in China and stronger-than-expected growth in Japan and India as consumers are running down savings accumulated during the pandemic, leading to notable strength in the services sector.

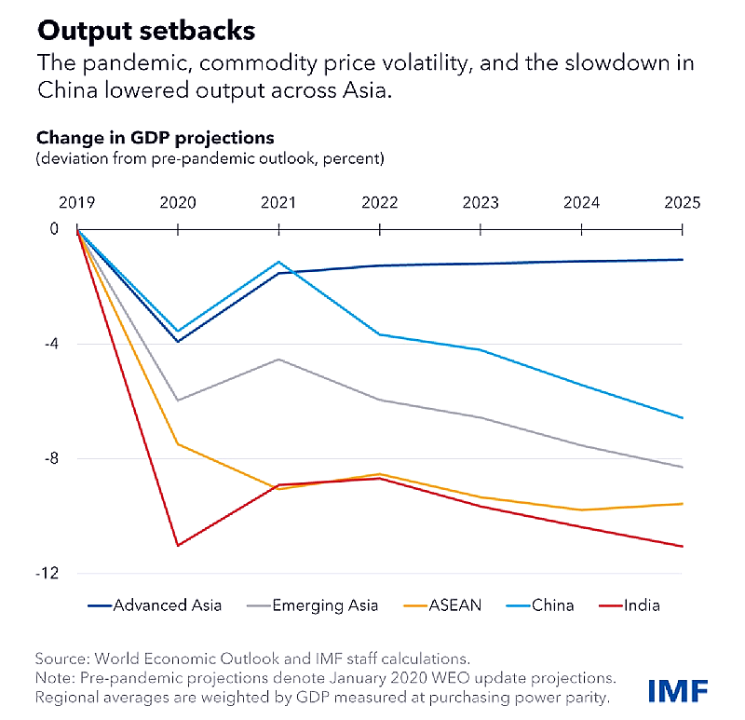

While Asia is still set to contribute about two-thirds of all global growth this year, it is important to note that growth remains too slow to make up for the output lost during the pandemic and the series of global shocks that followed.

The region’s growth next year will slow to 4.2 percent. Our less-optimistic assessment is based on the recent slowing in momentum including from the deepening property-sector slump in China which will affect commodity exporters with close trade links to China in particular.

Beyond this, an aging population and slowing productivity growth will further temper growth over the medium-term in China, amid rising risks of geoeconomic fragmentation, and bear upon prospects in the rest of Asia and beyond.

In a downside scenario where “derisking” and “reshoring” strategies take hold, Asian economies could be adversely affected significantly.

Faster growth in the United States and Japan is insufficient to offset this drag from China.

The strength of the US economy is taking place in the services sector, rather than in goods. And US policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS and Science Act are re-orienting demand toward domestic sources. Both factors don’t bode well for Asia’s exports.

On the bright side, Indonesia’s growth is projected to remain robust at 5 percent in 2023 and 2024, among the best globally, with continued strong domestic demand and prudent macro-financial policies.

A welcome development is that disinflation is on track in Asia, with inflation now expected to return to central bank target ranges next year in most countries.

Indonesia has already brought overall and core inflation back well into the inflation target band, after the decisive tightening of the policy rate, complemented with higher reserve requirements.

This process is well ahead of most other regions, where inflation remains high and is expected to fall within target only in 2025.

Inflation has risen in Japan, where the central bank has twice tweaked its yield curve control policy settings to manage risks to the outlook.

Given the large participation of Japanese investors in global markets, we find that these policy actions led to spillovers in other bond markets.

These could become larger in the event of a more substantial normalization of monetary policy in the region’s second-largest economy.

The global environment remains highly uncertain, and while risks to the outlook are more balanced than they were six months ago, Asia’s policymakers must stay the course to ensure continued growth and stability.

Aside from the aforementioned downside risks from China, a sudden tightening of global financial conditions could lead to capital outflows and put pressure on Asia’s exchange rates that would threaten the disinflation process.

Where tight monetary conditions are straining financial stability—including through the real estate sector and heavily indebted companies—supervisors must monitor systemic risks closely.

In many of the region’s emerging market and developing economies, including Indonesia, financial conditions have remained relatively accommodative and real policy rates close to neutral levels.

This has reduced the need for an early loosening of monetary policy in the region more broadly and indeed, in the case of Indonesia, allowed room for taking welcome preemptive action to increase rates against potential imported inflation.

And with public debt still high across most of the region, the ongoing gradual fiscal consolidation should continue to build room for maneuver and to ensure debt sustainability.

For those emerging market and developing economies like Sri Lanka that are suffering from funding stress on external markets, faster and more efficient coordination on debt resolution is needed.

Again, Indonesia stands out as a relative beacon of stability, with comfortable policy space and robust buffers, including from low government deficits, high cash reserves, and declining public debt.

As long-term prospects dim, countries must redouble their efforts to advance growth-enhancing reforms.

For Indonesia, raising government revenue ratios from low levels and reducing the cost of fuel subsidies would allow for additional spending on important needs such as education, health, and infrastructure while preserving its long-standing and hard-earned prudent fiscal stance.

Strengthening human and physical capital will allow Indonesia to take full advantage of its demographic dividend and vast natural resources, enabling productivity, diversification and value added, and help with mobilizing private financing for climate change transition and adaptation and the creation of high-quality jobs in support of its long-term vision.

Finally, strengthening multilateral and regional cooperation and mitigating the effects of geoeconomic fragmentation are increasingly vital for Asia’s economic outlook in coming years.

To that end, reforms that lower non-tariff trade barriers, boost connectivity, and improve the business environment are essential to attract more foreign and domestic investment across the region.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT