GOHALOPATA, India: Decades after inspiring a best-selling novel that brought readers into slums near Kolkata, 86-year-old ascetic Gaston Dayanand is still working for India’s poorest.

His life helping people in the mega-slums of Pilkhana formed the plot of Dominique Lapierre’s 1985 book “The City of Joy” which was later turned into a Patrick Swayze movie.

Born in 1937 to a Swiss working-class family in Geneva, Brother Gaston said he remembered deciding at six years of age to dedicate his life “to Christ and the poor.”

“I never wanted to be a priest,” the brother of the Prado congregation told AFP at the Inter-Religious Center of Development (ICOD), an NGO he co-founded in Gohalopata, a village 75 kilometers southwest of Kolkata.

“The church would never have let me live in a slum with the poor, but my life was about sharing with the poorest.”

A trained nurse, Brother Gaston arrived in India in 1972 to work with a French priest in a small self-help center in Pilkhana.

“It was the biggest slum in India at the time, they said in the world!”

Having arrived on a tuk-tuk, he surprised the local residents by entering on foot.

“I didn’t want to enter a place where there are so many poor people, on a rickshaw, like a rich person,” he said.

“I went to places where there were no doctors, no non-governmental organisations, no Christians. That is to say, places that were completely abandoned.”

‘Chicago on the Ganges’

One day in 1981, Brother Gaston said he received a visit from Dominique Lapierre, who was “sent by Mother Teresa.”

The well-known French author, who wanted to write a novel “about the poor,” convinced the ascetic of his sincerity.

The two men became friends.

Lapierre, who died last December, described Brother Gaston as “one of the ‘Lights of the World’ whose epic of love and sharing I had the honor of recounting in my book ‘The City of Joy.'”

Translated throughout the world, Lapierre’s novel, published in 1985, sold several million copies.

“He financed all my organizations at a rate of $3 million a year, almost all his royalties, for almost 30 years,” Brother Gaston said.

But the film adaptation of the novel, in which Swayze plays a fictional doctor, displeased him: “I frankly hated this film. ‘The City of Joy‘ has become ‘Chicago on the Ganges.'”

Surrounded by leprosy

At the time of Lapierre’s visit, Mother Teresa was receiving medicine from all over the world.

She donated large quantities to the self-help center, which Brother Gaston was able to use.

He trained nurses and established a dispensary.

“I had the medicine, I didn’t need anything else,” he said.

“We quickly had more than 60,000 patients the first year, 100,000 the second. Three years later, we had a small hospital.”

As soon as he arrived in India, he decided to adopt the nationality.

“It took 20 years, of course,” he said.

Brother Gaston was born with the surname Grandjean.

In India, he chose the surname “Dayanand”, meaning “blessed (ananda) of mercy (daya).”

He worked for a long time with Mother Teresa’s brothers caring for people suffering from leprosy in Pilkhana.

“I stayed for 18 years, surrounded by 500 lepers, in a very small room,” he said.

Abdul Wohab, a 74-year-old social worker, said: “Gaston is a saint.”

‘A board to sleep on’

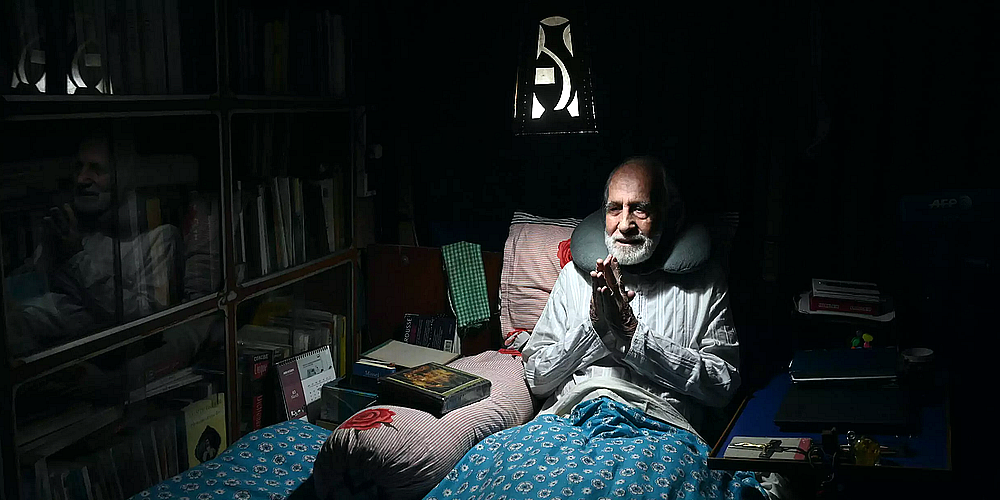

Now white-haired and confined to a wheelchair, Brother Gaston is still trying to help those in need in the northeastern province of West Bengal.

Of the 12 NGOs he founded since moving to India, six are still active, including the ICOD, which has taken in 81 people of all faiths, including orphans and the elderly, as well as those suffering from disabilities and mental health problems.

Brother Gaston said he spends “three-quarters of (his) days meditating” on his bed, facing Christ.

“I had never had anything else but a board to sleep on. Now I live like a bourgeois in a big bed,” he said.

“But it’s not me who wanted it,” he added with a laugh.

“The worst part is that I accept it.”

The ICOD’s co-founder and director, Mamata Gosh, nicknamed “Gopa”, watches over the man who taught her to be a nurse 25 years ago.

“Before him, I didn’t know anything,” the 43-year-old told AFP.

“He is my spiritual father.”

Brother Gaston’s day begins at 5:00 am with three hours of prayer, in front of a reproduction of the Shroud of Turin overhanging an Aum, the symbol of Hinduism, in his tiny oratory adjoining his room.

Dressed all in white and barefoot, he sits in his electric wheelchair and visits each of the residents of the thatched hamlet, then returns to his room in the late morning.

On his bedside table sits a Bible, a crucifix, his glasses and an old laptop that he uses to keep in touch with his NGO’s donors.

“I will earn my bread until the last day of my life,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT