Comment on “Social Justice and Affirmative Action in Malaysia: The New Economic Policy after 50 Years.” Kwame Sundaram Jomo, Asian Economic Policy Review, Volume 18, Issue 1, January 2023, pp 120-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12411. First published: 26 September 2022.

Any meaningful assessment of Malaysia’s New Economic Policy (NEP) (Lee, 2022) should be historical. One question which arises here is how one does historical political economy. After all, there are many different schools of political economy, even if few have addressed “affirmative action.”

A key question is how one treats normative issues that inevitably come up. How one understands notions such as “social justice” has long been contested. These are often understood and invoked very differently. And how is a term such as “affirmative action,” which arose in response to US civil rights struggles in the middle of the 20th century, to be understood in other contexts?

When first announced to the Malaysian nation in mid-1971, the NEP was presented as being needed for building “national unity” following the divisive events of May 1969. The NEP has often been presented officially and by others as responding to “race riots” following the young nation’s third general elections in which the incumbent multi-ethnic Alliance coalition lost its electoral majority. This perspective implies inter-ethnic economic disparities were responsible for “May 1969.”

Anand’s (1982) Theil decomposition suggests that less than a tenth of overall income inequality in 1970 (before the NEP) could not be explained by various non-ethnic factors such as education. Anand concludes that, at most, only a corresponding share of income inequality can be attributed to ethnicity.

His analysis implies there is limited scope for reducing overall income inequality by reducing inter-ethnic disparities. The NEP’s primarily ethnic focus for over half a century is hence unlikely to significantly lower economic inequality in Malaysia. Unsurprisingly, despite over half a century of the NEP, total income inequality remains high, even if underestimated.

Equating “social justice” with efforts to reduce inter-ethnic disparities is problematic. Supported by and responsive to the newly emerging Malay “middle class,” the new Malaysian regime defined “restructuring society” as one of the two NEP targets. This has been mainly understood as “positive discrimination,” or affirmative action, along ethnic lines, to eliminate the identification of “race” with “economic function.”

Defining social justice in terms of achieving affirmative action policy is problematic. Such a definition also effectively rejects other possible interpretations of “social justice,” for example, in terms of “abolishing class exploitation,” or achieving low income or wealth inequality, or reducing disparities among different regions.

Sabah and Sarawak state rights within the Malaysian federation did not preoccupy Prime Minister Razak during 1969–1971. However, this omission in the NEP’s ostensible social justice agenda is probably not acceptable to East Malaysians who believe they have not gotten a fair deal from the demographic majority in Peninsular Malaysia. Others might insist that overcoming gender and other inequalities is fundamental to any social justice agenda.

How do we compare other affirmative action policies, such as contemporary Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) in South Africa? What about pro-Afrikaner apartheid policies which also claimed to catch up with the previously dominant “Anglo-white” minority? What are the implications of such policies when introduced and implemented by demographically and politically dominant cultural majorities, as in South Africa, Malaysia, and, arguably, Hindutva India?

And how do we analyze similar policies in different contexts? For example, BEE in South Africa is generally acknowledged as being inspired by Malaysia’s NEP. Ironically, BEE has since been re-imported into Malaysia as “Bumiputera economic empowerment,” even using the same BEE acronym.

And how does a society decide on what is a legitimate and acceptable social justice agenda? Who decides and how? Invoking notions of “equality” and “fairness” hardly resolves the difficult issues to be resolved. Affirmative action seems to suggest the acceptability of otherwise unequal societies in which aggrieved groups are proportionately represented.

It also begs the question of affirmative action for other aggrieved groups which are minorities or not politically dominant. What does social justice in India imply, especially for its scheduled castes and tribes? Or for US ethnic minorities, including the descendants of Native Americans or African American slaves? And when does addressing a grievance support “social justice”? After all, apartheid was seen as a means for Afrikaner “ethno-populists” to achieve parity with Anglo-South Africans.

After eloquently exposing the policy cul de sac the NEP is in, it is curious that Lee still insists “Malaysia needs a systematic and comprehensive reset of the NEP’s (restructuring) prong.” This precludes a broader, more progressive approach to accelerate development more equitably. After all, in 1971, Razak already envisaged a Malaysian nation with comprehensive and universal social security.

References:

- Anand S. (1982). Inequality and Poverty in Malaysia: Measurement and Decomposition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lee H.A. (2023). Social justice and affirmative action in Malaysia: the new economic policy after 50 years. Asian Economic Policy Review, 18(1), 97– 119.

This article was originally published on KSJomo.org.

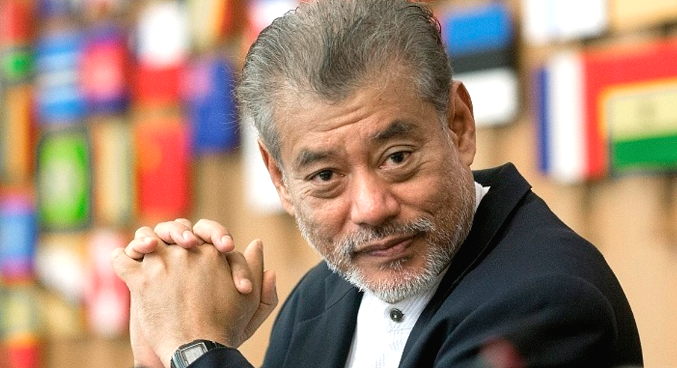

(Jomo Kwame Sundaram was an economics professor and United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT