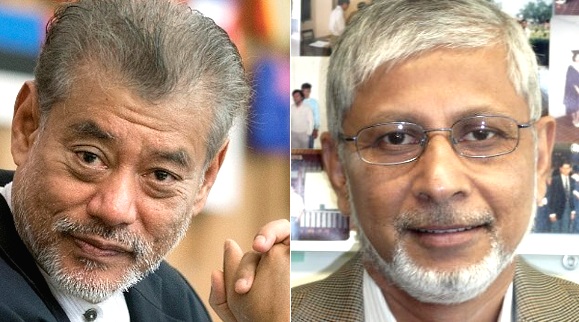

By Jomo Kwame Sundaram / Anis Chowdhury

COVID-19 has set back the uneven progress of recent decades, directly causing more than two million deaths. The slowdown, due to the pandemic and policy responses, has pushed hundreds of millions more into poverty, hunger and worse, also deepening many inequalities.

Development setbacks

The outlook for developing countries is grim, with output losses of 5.7% in 2020. Compared to pre-pandemic trends, the expected 8.1% loss by end-2021 will be much worse than advanced countries dropping 4.7%.

COVID-19 has further set back progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). As progress was largely ‘not on track' even before the pandemic, developing countries will need much support to mitigate the new setbacks, let alone get back on track.

The extremely poor, defined by the World Bank as those with incomes under US$1.90/day, increased by 119–124 million in 2020, and are expected to rise by another 143-163 million in 2021.

Fiscal response constrained

Global fiscal efforts of close to US$14tn, plus low interest rates, liquidity injections and asset purchases by central banks, have helped. Nonetheless, the world economy will lose over US$22 trillion during 2020–2025 due to the pandemic.

Government responses have been much influenced by access to finance. Developed countries have accounted for four-fifths of total pandemic fiscal responses costing US$14tn. Rich countries have deployed the equivalent of a fifth of national income for fiscal efforts.

Meanwhile, emerging market economies spent only 5%, and low-income countries (LICs) a paltry 1.3% by mid-2020. In 2020, increased spending, despite reduced revenue, raised fiscal deficits of emerging market and middle-income countries (MICs) to 10.3%, and of LICs to 5.7%.

Government revenue has fallen due to lower output, commodity prices and longstanding Bank advice to cut taxes. Worse, they already face heavy debt burdens and onerous borrowing costs. Meanwhile, private finance dropped US$700bn in 2020.

Developing countries lost portfolio outflows of US$103bn in the first five months. Foreign direct investment (FDI) flows to emerging and developing countries also fell 30–45% in 2020. Meanwhile, bilateral donors cut aid commitments by 36% between 2019 and 2020.

Meanwhile, the liquidity support, debt relief and finance available are woefully inadequate. These constrain LICs' fiscal efforts, with many even cutting spending, worsening medium-term recovery prospects!

Debt burdens

In 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) assessed half the LICs as being at high risk of, or already in debt distress – more than double the 2013 share. Debt in LICs rose to 65% of GDP in 2019 from 47% in 2010.

Thus, LICs began the pandemic with more debt relative to government revenue, larger deficits and higher borrowing costs than high-income countries. And now, greater fiscal deficits of US$2–3tn projected for 2021 imply more debt.

Debt composition has become riskier with more commercial borrowing, particularly with foreign currency bond issues far outpacing other financing sources, especially official development assistance (ODA) and multilateral lending.

More than half of LIC government debt is non-concessional, worsening its implications. External debt maturity periods have also decreased. Also, interest payments cost more than 12% of government revenue in 2018, compared to under 7% in 2010.

Riskier financial flows

Developing economies have increasingly had to borrow on commercial terms in transnational financial markets as international public finance flows and access to concessional resources have declined.

Low interest rates, due to unconventional monetary policies in developed countries, encouraged borrowing by developing countries, especially by upper MICs. But despite generally low interest rates internationally, LIC external debt rates have been rising.

Overall ODA flows – net of repayments of principal – from OECD countries fell in 2017 and 2018. Such flows have long fallen short of the financing needs of Agenda 2030 for the SDGs. Instead of giving 0.7% of their national income as ODA to developing countries, as long promised, actual ODA disbursed has yet to even reach half this level.

Although total financial resource flows (ODA, FDI, remittances) to least developed countries (LDCs) increased slightly, ODA remained well short of their needs, falling from 9.4% of LDCs' GNI in 2003 to 4.3% in 2018. Meanwhile, FDI to LDCs dropped from 4.1% of their GNI in 2003 to 2.3% in 2018.

There has also been a shift away from 'traditional' creditors, including multilateral financial institutions and rich country Paris Club members. Some donor governments increasingly use aid to promote private business interests. 'Blended finance' was supposed to turn billions of aid dollars into trillions in development finance.

But the private finance actually mobilized has been modest, about US$20bn a year – well below the urgent spending needs of LICs and MICs, and less than a quarter of ODA in 2017. Such changes have further reduced recipient government policy discretion.

Inadequate support

The 2020 IMF cancellation of US$213.5m in debt service payments due from 25 eligible LICs was welcome. But the G20 debt service suspension initiative (DSSI) was grossly inadequate, merely kicking the can down the road. It did not cancel any debt, with interest continuing to accrue during the all-too-brief suspension period.

The G20 initiative hardly addressed urgent needs, while private creditors refused to cooperate. Only meant for LICs, it did not address problems facing MICs. Many MICs also face huge debt, with upper MICs alone having US$2.0–2.3tn in 2020–2021.

World Bank President David Malpass has expressed concerns that any change to normal debt servicing would negatively impact the Bank's standing in financial markets, where it issues bonds to finance loans to MICs.

The Bank Group has made available US$160bn for the period April 2020 to June 2021, but moved too slowly with its Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF). By the time it paid out US$196m, the amount was deemed too small and contagion had spread.

Special drawing rights

Issuing US$650bn worth of new special drawing rights (SDRs) will augment the IMF's US$1tn lending capacity, already inadequate before the pandemic. But US$650bn in SDRs is only half the new SDR1tn (US$1.37tn) The Financial Times considers necessary given the scale of the problem.

To help, rich countries could transfer unused SDRs to IMF special funds for LICs, such as the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) and the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), or for development finance.

Similar arrangements can be made for the Bank. A World Bank version of the IMF's CCRT could ensure uninterrupted debt servicing while providing relief to countries in need. Investors in Bank bonds would appreciate the distinction.

Hence, issuing SDRs and making other institutional reforms at the Spring meetings in April could enable much more Fund and Bank financial intermediation. These can greatly help finance urgently needed pandemic relief, recovery and reforms in developing countries.

This article was originally published on KSJomo.org.

(Jomo Kwame Sundaram was an economics professor and United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development; Anis Chowdhury is Adjunct Professor, Western Sydney University and University of New South Wales, Australia.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT