Malaysia is facing the nexus of three fundamental problems, all related to human capital weaknesses—the brain drain issue, the education system crisis and the governance crisis. The three reinforce each other to make us lose talents exponentially, as the global data available over the years suggests (see “Malaysian brain drain – don’t go chasing waterfalls”). If all three remain unchecked, Malaysia is about to lose its lock, stock and barrel.

Brain drain

Already in April 2011 World Bank (“Malaysia Economic Monitor: Brain Drain”, pp. 12 – 13) found that 2 out of 10 Malaysians with a tertiary degree migrate. In other words, 20% of Malaysians with tertiary degrees choose to advance the foreign economies. This statistic should have shocked us back then.

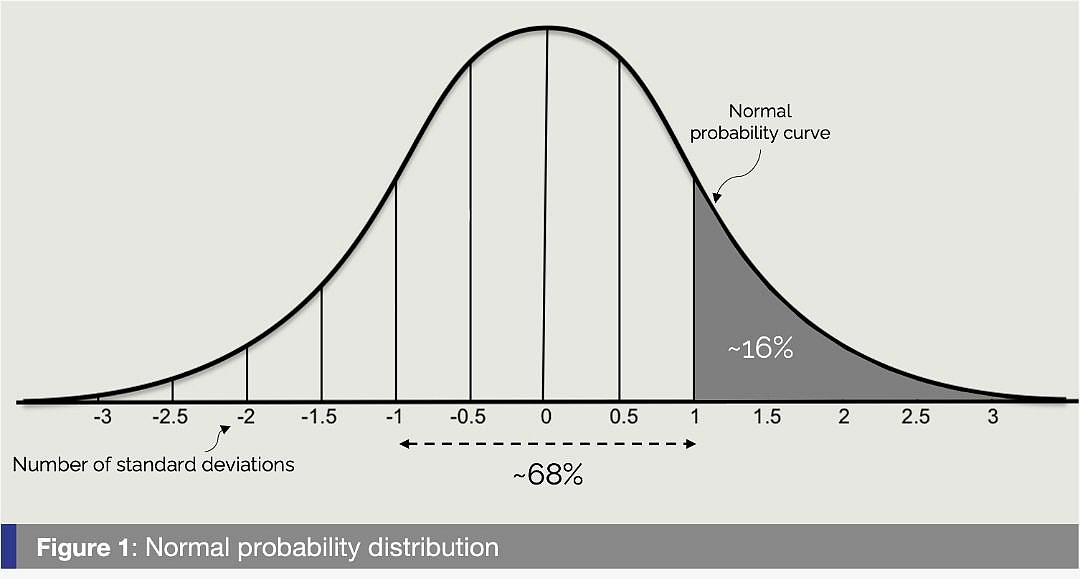

To understand the gravity of this statistic for a country, let’s remember the established general fact that the Gaussian normal distribution well approximates the distribution of human intelligence in the population (see figure below).

Therefore, 68% would be average (in the middle), and the distribution is symmetric. So, this leaves us with 16% on the right-hand tail — those with extremely high potential for creating new knowledge, the very best. And here we are losing 20% of those with a tertiary degree already in 2011. Therefore, there is a high chance of losing those crèmes de la crème professionals on a massive scale within this category.

And this has been happening to our country already in the 2010s! So, we should be alarmists already then.

Education system crisis

Already in 2009, World Bank, based on its surveys, reported a serious shortage of high technical skills in Malaysia, including among the fresh graduates, therefore, reflecting severe problems within the education system.

This dynamic continued well into 2015 and till now. The TalentCorp has consistently reported an industry-wide inability to fill in the critical occupations related to high technical skills such as ICT, electronics, engineering and research consistently since 2015 until now.

Fair enough, in the latest World Bank report on Malaysia 2021, the need to create and retain high-skilled talents was underscored almost in every second paragraph as the critical obstacle.

Meanwhile, education is a social function of society formation, without which society simply cannot exist.

Governance crisis

At the same time, Malaysia has an ongoing governance crisis at every level of society.

We talk about corruption these days as often as we talk about the brain drain issues, not by coincidence. The empirical research on brain drain in the Malaysian context consistently identified corruption as one of the “push factors” – factors making our highly skilled compatriots look for better opportunities abroad.

A country is a complex social system in which small changes can propagate quickly. And the country’s destiny is made at every point in the society where decisions are made, big or small, strategic or mundane, day-to-day decisions. When these decisions are not made based on merit and credibility, the country, as a complex social system, starts losing its plot and wanders aimlessly.

This is why, as of what can be observed lately from the global data, if Malaysia’s strategic policy-making is keeping up with anything, then only with the global anti-trends.

NONE of the 70 countries already rolling out 5G follows the problematic Single Wholesale Network model – we do (see “DNB’s window dressing”).

NONE of our regional peers overindulges in price controls – Malaysia is reported to have one of the highest (times over) number of food price controls in the East Asia Pacific region (World Bank staff compilations, Batmunkh & Pfutze, 2022).

The best performing Sovereign Wealth Funds highly diversify their investments worldwide to minimise the possibility of corruption and overheating of the home economy – we concentrate such the strategic investments within the local government-linked organizations and local government bonds (see “EPF: Elbowing financial repression, embracing radical transparency”).

Other countries have been steeply increasing their arable lands over the last three decades – we have been gradually reducing (see “Food Insecurity: Learn from Past Policy Failures”).

And the list can go on.

Apart from that, the main anti-trend that continues hurting Malaysia the most is that it continues to pursue the factor accumulation for its engine of economic growth—focusing only on the quantity of the four primary factors of production: labour, land, capital and entrepreneurship.

Meanwhile, the rest of the world, as early as the 2000s, has graduated from the factor accumulation to the path of innovation with an intrinsic focus on the quality of all the factors: if labour, then knowledge-workers rather than low-skilled workers, if entrepreneurship then it is all about digitisation, digitalisation and digital transformation rather than manual work.

Contrary to the notion of comparative advantage and economies of scale, as both do not exist in the 4IR world, these countries, one by one, started to turn their focus inward to localise their supply chains through extensive use of technologies while increasing the breadth and depth of their local industries and therefore high-paid job opportunities.

On the contrary, Malaysia appears to be stuck with a very simple economy for over two decades — we are either on one end of the global supply chain (supply of raw materials) or at the other (simple assembly of finished goods). What about all that void in-between? We import!

However, what would happen to such an economy when the global supply chain starts to unravel? This unravelling began a long time before the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic and recent geopolitical events have only accentuated the trend.

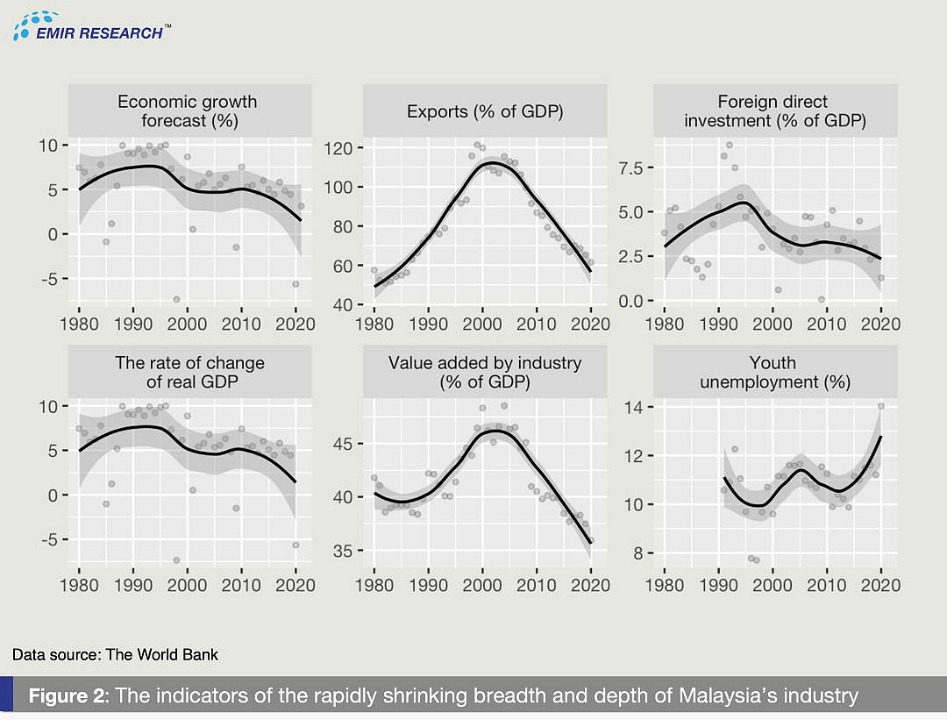

There are robots now all over the world doing simple assembly of finished goods — robots assisted by intelligent and highly skilled human beings, some of whom are sadly our compatriots. Other countries are investing in robots to perform these low-skill mundane automated jobs while also investing in human capital. This is why we see such a profound decline in our exports and value-added by industry in Figure 1 (note a clear structural break happening around the late 1990s/early 2000s).

Malaysia’s economy has long time been dependent on oil export. Now every country is rushing to renewable energy sources.

How long would we be able to hold trying to face 2020s problems with 1980s solutions? How much more room has Malaysia left to manoeuvre among the anti-trends?

We should stop looking for positives in disasters we face, be it drains or floods. This is not the type of creative thinking that we need. The disasters must be addressed through credible policy-making rather than pure narrative management. We should stop doing jihad on the consequences of our disastrous management but do the real jihad on the root causes.

Remember again, the destiny of a country is made at every point where the decision is made. Therefore, there is a simple thing we all can do – for example, exert a zero-tolerance to corruption at the individual level in the form of personal unacceptance and unacceptance towards those whom we know to practice it, no matter how it is packaged or under which sauce it is presented to us, ethnic, religious, political. Wrong is wrong.

This is when everything will start to fall into place by itself, including the brain drain reversal, because, at every level of society, resources will begin to flow based on merit and credibility where they are the most needed!

Our Nation, our Malaysia, is at a critical junction. Like an orphan, it is standing by the side and probably crying and waiting when the real Mat Kilau will wake up in every single one of our vibrant almost 33 million people here and start making their day-to-day decisions based on merit and credibility in the true patriotic spirit.

(Dr. Rais Hussin and Dr. Margarita Peredaryenko are part of the research team at EMIR Research, an independent think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT