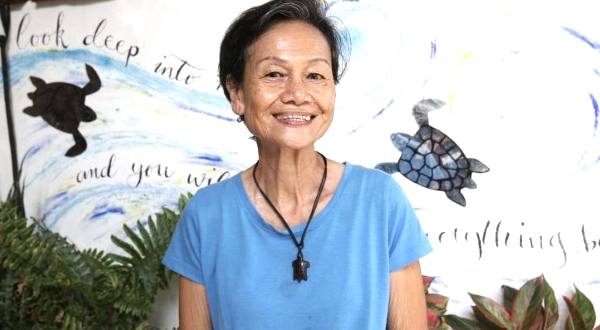

If you want to talk about the turtle conservation work in Malaysia, there's a person you cannot ignore, who is Professor Chan Eng Heng, a retired professor of The University of Malaysia Terengganu(UMT).

Chan Eng Heng has been doing research on turtles for many years and has successfully prompted the Terengganu government to take action to protect turtles, such as amending the enactment to prohibit the sale of certain species of turtle eggs, and turning nesting beaches in Redang Island to turtle sanctuary. The Sea Turtle Research Unit (SEATRU) which co-founded by her is also famous, attracting many people from here and abroad to volunteer in Terengganu. It is roughly estimated that in the past few decades, a total of nearly 500,000 turtle eggs have been saved.

If you want to know the conservation history of sea turtles in Malaysia, you cannot miss the story of Chan Eng Heng.

Chan Eng Heng retired in 2009 and currently lives in Kuala Lumpur, living a sustainable lifestyle. Her house is easy to identify due to the numerous turtle decorations, which indicates that the owner of the house is a person who loves turtles very much.

However during the interview, she said she initiated the turtle research not because she loved turtle, but because she was asked by university to do so. In the early 1980s, she was teaching in the Faculty of Fisheries in UPM (formerly known as Universiti Pertanian Malaysia). One day, the director of Terengganu Fisheries Department asked the university to save leatherback turtles as the population of leatherback turtles was declining.

"At that time, there were very few staffs in the Terengganu campus. I was one of the few. My boss said, 'Chan, you go lah'. I said okay. That's why I started to study turtles. Later on, as I got deeper and deeper into the research work, I discovered how little we know about turtles. The more you study about something, the more you realize there's still so much to study. So I guess that's how my passion developed."

It seemed like she was the only one in Malaysia doing research on sea turtles at that time. Everything had to start from scratch. Moreover, there was no internet in those days. So she wrote to foreign experts.

"Fortunately, they were very kind. When I wrote to them for help, a lot of them wrote back and sent me articles. There was even a couple offering to come over and help me."

In the 1980s, the number of leatherback turtles had declined by 95%. When she told the Terengganu state government about that, the officers felt unbelievable. "I said I didn't make up the figures. All these figures were based on statistics. They were shocked. And they started doing something."

The Terengganu state government amended the Turtle Enactment in 1980s to prohibit the sales and consumption of leatherback turtle eggs. And the state government also set up a Turtle Sanctuary Advisory Council. She was one of the council members and used this platform to give suggestions on conservation work.

From research to conservation

At the beginning, she studied leatherback turtles in Rantau Abang and did radio tracking work. Later on, she extended the study to cover the green turtles in Redang Island.

It was just research in Redang Island initially. However, "when I was doing the research, the egg collectors came to the beach every morning and took out all the eggs from the nests, and then to sell and to eat. I couldn't help thinking what's the point of doing all these research if I couldn't save the eggs? So I decided to start conservation work as well," she said.

One of her major contributions was the establishment of SEATRU. SEATRU has been stationed in Chagar Hutang in the northern part of Redang Island since early 1990s. The turtles that come ashore to lay eggs there are mainly green turtles and occasionally hawksbill turtles. To prevent the turtle eggs from being consumed by humans, the direct way is to buy all the turtle eggs from the egg collectors.

There was a consortium planning to build a hotel in Redang Island at that time. This consortium was willing to work with her and provide the fund for SEATRU to buy turtle eggs from egg collectors. However, the luck did not last long. In 1997, the consortium stopped the funding due to financial crisis. She worried that if there's no money to buy the turtle eggs, the turtle eggs might be gone. Fortunately, "it's like angels sending idea to me, telling me to start a volunteer program," she said. And this is how the SEATRU volunteer program got started.

Unlike other volunteer programs, SEATRU volunteers are not paid. In contrast, they have to pay a few hundred ringgit if they want to join the program. And the fee will be channeled to fund the conservation work. The project has got very good response since 1998 from locals and foreigners.

Chan Eng Heng remembers that when she told her colleague about this program, her colleague laughed and said, "Chan, you ask people to come and work with you, and you ask them pay you some more? How can?" In fact, she didn't know if this program would work. But she had to give it a try anyway.

Surprisingly, the program has got very good responses since it was launched. Moreover, some other conservation groups also use the same approaches to recruit volunteers.

There's also a nest adoption program under SEATRU. All nests are marked. SEATRU will inform the people who adopt the nests when the eggs finally hatched.

And after many years of lobbying and advocacy, the Terengganu state government had finally gazetted the nesting beach in Redang Island as a turtle sanctuary around 2005. This was one of the happiest moment in her life.

When it comes to conservation, the most effective way is to educate the people at an early age. This was why Chan Eng Heng started an annual children camp for the Standard Five Children of Redang Island. The objective of this "Kem Si Penyu" was to raise awareness of protecting sea turtles since the kids were young. In addition, she has published two children's books, a coloring book and another titled "Little Turtle Messenger".

She retired from Universiti Malaysia Terengganu in 2009. After retirement, she continued making contributions, such as creating a Turtle Alley in Kuala Terengganu and co-founding the Turtle Conservation Society of Malaysia with former student Chen Pelf Nyok.

When she first started studying sea turtles, her children were still very young. She often went to Rantau Abang doing research at night, and then rushed home the next morning to send her kids to babysitter and rushed to university later on. She could handle this very well when she was young. "Now cannot loh," she said.

In those days, people were unaware of the importance of protecting animals. She once thought that there might be some people who were upset at her, especially when the nesting beaches were gazetted as turtle sanctuaries. Surprisingly, the villagers did not boycott her. Part of the reasons might be her good deeds for the villagers.

After working hard for so many years, she still feels something are unfulfilled. For example, some people keep selling turtle eggs and the poor leatherback turtles as she predicted, have almost disappeared in Terengganu.

Anyway, the good thing is there are more and more conservation groups nowadays and people are more aware about the importance of turtle conservation. When she revisited Redang Island two years ago, some villagers told her that they had never consumed turtle eggs anymore since participating in the Kem Si Penyu.

Life after retirement

Last year, the International Sea Turtle Society awarded her a lifetime achievement award. This award is considered the ultimate award in the field of turtle conservation.

At present, she is still the president of Turtle Conservation Society of Malaysia. She is now passionate about gardening. The front yard, backyard and even the roof of her house are her gardens. She has also established a Facebook group called the Klang Valley Plant Exchange.

She remains very active although she injured her back recently. She is 70 years old, "but what I do now is actually the same as what I did at 30," she said.

She always believes that if we do something wholeheartedly, help will come our way somehow. But, "you must do it yourself, cannot cincai cincai," she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT