During the Covid-19 pandemic, I often felt like I was trapped in the same nightmare, or living in a hell with no exit.

I saw healthcare workers break down, forced to decide who would live or die because of a shortage of oxygen tanks.

I heard funeral workers talk about the dead “lining up” for a week before they could be cremated.

I personally witnessed critically ill patients lying under transparent isolation hoods like dead fish waiting to be devoured by the virus.

More absurdly, the person I video-called most often was not a friend or relative, but a virologist.

Almost every other day, I had to go live with them, following the virus mutations like watching a drama series.

For ordinary people, the only worry might be “Will I get infected?” But for journalists, our daily work was like writing a serialized horror novel—because the virus was like a ghost, invisible to the eye yet everywhere at once.

In those days, my colleagues and I were in terrible mental states. Every morning, we woke up only to face new tragedies.

By the end of 2022, I finally quit my job as a TV journalist due to overwhelming stress. I thought I had escaped the “medical field,” but ironically I only went from white-coated doctors to shamans in the tropical rainforest.

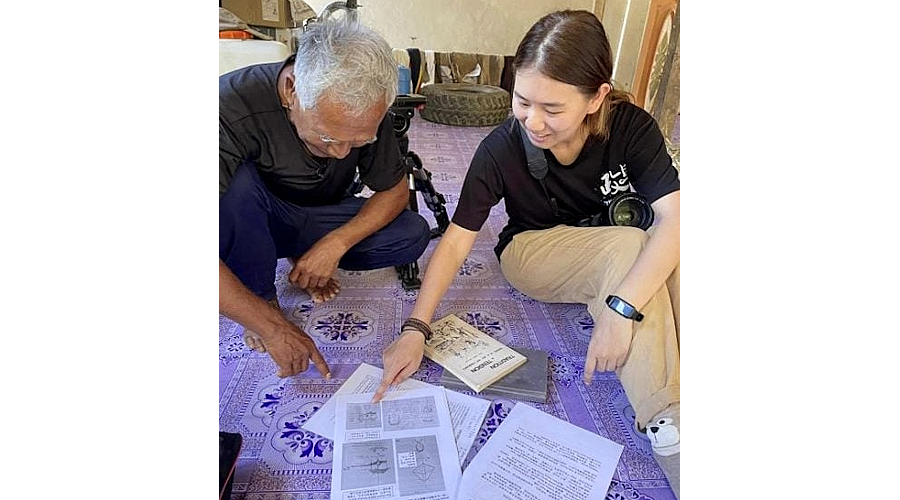

At first, I was only helping a local TV station film a folk culture program, searching for traditional healing practices on the brink of disappearing. But one thing led to another, and it somehow became the subject of my Master’s thesis.

Finding shamans willing to be filmed, however, was no easy task.

Many indigenous communities share a common taboo: healing rituals must be performed in complete darkness, no outsider, filming or recording permitted.

What happens if the taboo is broken? At best, the camera fails or strange sounds appear on the recording. At worst, souls may be lost—or the shaman may die. As you can imagine, I encountered them all.

Over these years, I often ventured alone into deep forests, listening at night to shamans chanting spells and burning kemenyan incense to connect this world with “the other world.”

I saw patients suddenly wail after being possessed by spirits, and I witnessed rituals cut short by ancestral spirits warning the shaman that if the healing continued, everyone present would lose their souls and never return.

But the most terrifying experience was my encounter with the Jah Hut tribe’s healing puppet—the sepili.

Stolen souls cause illness; puppets subdue evil spirits

The Jah Hut believe each person has seven ruay (souls/spirits). If even one is stolen by an evil spirit—called bes—the person will fall ill.

To retrieve the lost ruay, the shaman, aided by spirit companions, identifies the culprit and instructs the tribe to carve a specific puppet to capture it.

Each sepili puppet resembles the bes itself. Their forms vary: some human-like, some beastly, some holding weapons—all eerie and uncanny.

To combat these ever-present spirits, elders pass down each bes’s story and image orally.

Every Jah Hut boy grows up learning to carve these puppets.

Shamans told me there are hundreds of puppet types, each corresponding to certain symptoms.

For instance, if a patient suffers headaches, the culprit might be Bes Rungkup Tajam Kepala. If it’s insomnia, then perhaps Bes Yak Yung TT Galax.

The names sound like alien languages, but to the Jah Hut people, they strike fear like the words “cancer” or “new variant” in cities.

Of course, shamans don’t always use puppets; it depends on the severity of the illness.

The first stage of treatment, Muruk, involves the shaman chewing turmeric and applying the paste on the patient’s body.

The second, Tepung Alin, requires rolling dough over the patient to absorb the spirit.

If the case is severe, they move to the third stage, Trekben: placing the puppet on the back of the patient’s neck while chanting to draw out the bes.

Finally, using a weapon made of salak leaves, the shaman strikes the puppets before ordering assistants to throw them deep into the jungle where no one will go.

They must not look back—otherwise the spirits may follow and turn them into prey.

Being curious, I of course looked back, breaking taboos again, and soon strange, unexplainable events began to happen.

Taking puppets home and misfortunes follow

First, while filming a Trekben ritual, our camera suddenly malfunctioned—the battery inexplicably fell out, wiping out a full hour of footage.

Luckily, the ritual was repeated the second night, so we could reshoot.

Later, we filmed a Jah Hut man carving the puppet Bes Pintu Katak (“Frog at the Gate”), said to dwell by forest streams surrounded by stones that seep red liquid.

But when I later used AI to transcribe the interview, in the footage where the carver polished the puppet’s backside, a chilling sentence was detected: “How do you want me to come alive?”

The scariest part, however, happened when I brought the puppets home.

For filming, we had asked Jah Hut friends to carve eight puppets used in the ritual. They repeatedly warned us: once filming was over, the puppets must be broken and discarded in a remote place.

Naively, I thought unused puppets were harmless and kept them as souvenirs.

From the very day I took them home, I suffered relentless insomnia. My brainwaves felt “broken,” plagued by strange noises, my whole energy field disturbingly off.

I didn’t want to be dismissed as superstitious, so during those sleepless nights, I avoided connecting my misfortunes to the puppets.

But every time I tried to justify keeping them, calamity struck: I caught Covid-19, my house was burglarized, I developed unexplained ear infections, and strange growths appeared in my eyes.

After months of this torment, I received shocking news—the Jah Hut shaman had passed away.

Shaman’s death like a library burned to ground

In the indigenous world, they say: “When a shaman dies, it’s like a library burning down.”

I never truly grasped this saying until I heard of his passing. I felt as if ancient chants and ancestral wisdom had turned into dry leaves, slowly burning to ash in the rainforest.

I still remember the last time I saw him: I held his hands tightly, bowed deeply, hoping we would meet again. Only later did I realize—that was a farewell.

Though he was already ill, guilt surged in me. Did my ignorance of taboos hasten his death?

That night, I couldn’t sleep again. All I could see was his betel-stained gums, a red smile so vivid it seemed like proof he had chewed up evil spirits.

What unsettled me most was the sudden thought: Now that he was gone, who would subdue the spirits haunting me? Was it Bes Yak Yung TT Galax tormenting me?

Of course, I had no answer.

More on the Echoes of the Forest

(Yi Ke Kuik is a Master’s student in Anthropology at National Taiwan University focusing on issues related to indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Founder of myprojek04 photography initiative and writes for a column called Echoes from the Forest (山林珂普) in Sin Chew Daily, highlighting the photos and stories of indigenous people.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT