The right to protest is fundamental to any democratic society.

In Malaysia, where civic space has long oscillated between control and contestation, the ability to assemble peacefully in public is both a constitutional guarantee and a hard-won political practice.

Yet, as the Turun Anwar rally on 26 July demonstrated, the question today is no longer whether Malaysians can protest; but what protest now means, who it speaks for, and how it is being reshaped in ways that reveal deeper fractures in our political and civic imagination.

Far from being a mere gathering of discontented citizens, Turun Anwar serves as a window into the increasingly ambiguous role of protest in contemporary Malaysia.

It compels us to reflect on how protest is being used, understood, and interpreted; not simply as a form of dissent, but as a battleground of ideological positioning, historical amnesia, and symbolic contestation.

From civic tool to strategic theater

To understand the Turun Anwar protest is to confront the paradox of Malaysia’s maturing yet fragmented protest culture.

On one hand, protest is more visible and permissible than ever. Since the post-2018 transition, the fear of repression has softened in many quarters, and mass mobilization, whether for electoral reform, student issues, or identity-based claims, has entered the repertoire of political life.

Yet, the normalization of protest has brought with it a dilution of clarity.

Turun Anwar, which centered on public anger over inflation, subsidy restructuring, and unmet reforms, was organized by PAS Youth and supported by Perikatan Nasional (PN) figures; many of whom were once at the helm of government, wielding power without reformist credibility.

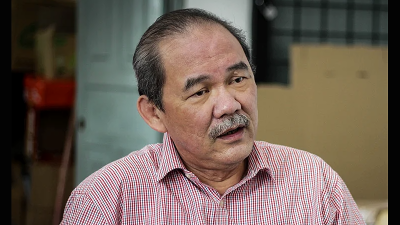

The presence of former prime ministers such as Mahathir Mohamad and Muhyiddin Yassin further deepens the irony: leaders who once invoked national security to suppress protest now marching in defense of the rakyat’s voice.

This is not merely political opportunism. It is strategic appropriation, a repurposing of the symbolic power of protest by political actors who understand its affective appeal, even if their governance record contradicts its democratic ideals.

In this shift, protest morphs into theatre, where the act of mobilizing becomes less about public deliberation and more about public optics.

The result is a form of protest that operates with internal contradictions: asserting popular will while recycling elite grievances, invoking moral outrage while offering no inclusive or coherent alternative.

Voices missing from the streets

Equally striking was not just who protested, but who didn’t. Many reform-oriented Malaysians, especially those who were once the backbone of street politics in the Reformasi and Bersih eras, abstained from Turun Anwar.

Their absence was not passive. It was politically charged.

This absence reveals how ideological authorship now determines the perceived legitimacy of protest.

Protest is no longer judged only by its cause but also by who organizes it, what symbols they invoke, and what values they foreground.

For many, to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with a movement led by PAS and PN, groups seen as espousing conservative ethno-religious agendas and illiberal tendencies, would be to compromise on pluralism and the more expansive civic ideals that once defined Malaysia’s protest movements.

This is a profound shift. Protest is no longer a neutral space of shared grievance. It has become ideologically coded, segmented by partisan affiliation, and shaped by identity politics.

In Turun Anwar, the protest space was saturated with Malay-Muslim symbolism and conservative moral framings.

While these are legitimate perspectives in a plural society, their dominance produced a kind of exclusionary affect, a sense that the rally was not for all Malaysians, even if the economic grievances it cited affected everyone.

The deeper implication is this: protest is no longer a unifying medium of political voice. It is a divided terrain, where participation is filtered through ideological comfort zones.

This is not necessarily new, but the starkness of the divide today, and the speed with which protest becomes a site of moral contestation, is increasingly evident.

The question is no longer simply whether one dares to protest, but what one is protesting for, who stands beside us, and whether protest is still capable of holding together the messy, pluralistic hopes of a democratic society.

From moral conscience to moral confusion

There was a time when protest in Malaysia, however contested, still carried an aura of moral resistance.

The Reformasi wave of 1998, the Hindraf movement in 2007, and the Bersih rallies of the 2010s represented diverse efforts to reclaim political agency.

These protests, despite their imperfections, drew moral authority from their structural critique of the state: corruption, electoral injustice, institutional decay.

Turun Anwar, by contrast, felt less anchored in moral vision than in moral confusion.

The slogans referenced the people’s suffering, but the protest lacked a transformative horizon. The criticism was sharp, but the alternative was vague.

This reflects a deeper crisis of political meaning in Malaysia, where protest is increasingly transactional, driven by who is in opposition rather than what is fundamentally at stake.

When protest becomes reduced to a rotational device, used by whichever side loses power, it no longer disrupts the status quo. It reinforces it. It produces the illusion of democratic energy without the substance of democratic renewal.

This is the protest paradox: the more accessible protest becomes, the more its symbolic potency weakens. Its ubiquity risks disenchantment, especially among a younger generation for whom institutional reform, rights discourse, and inclusive narratives once held promise.

The street no longer feels like a site of possibility. It is a site of repetition.

In such a context, many choose silence, not out of disengagement, but out of principled estrangement.

The refusal to join is a political act in itself: a rejection of being co-opted into protest performances that no longer align with ethical clarity or civic inclusiveness.

Turun Anwar will not be the last protest in Malaysia’s evolving democratic landscape. But it may well be remembered as a moment that crystallized the fragmentation of protest as political practice, when protest ceased to serve as a meeting point of citizen aspiration, and instead became a battleground of competing moral claims.

Protest remains vital. But as Turun Anwar has shown, the question is no longer simply whether one dares to protest, but what one is protesting for, who stands beside us, and whether protest is still capable of holding together the messy, pluralistic hopes of a democratic society.

In the end, the rally told us less about Anwar, and more about ourselves.

(Khoo Ying Hooi, PhD, is an Associate Professor of International Relations and Human Rights at Universiti Malaya. Her work spans human rights research, diplomacy, and policy engagement across ASEAN and Timor-Leste, along with active contributions in editorial and advisory capacities.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT