With the US government shutting door on “unconditional foreign aid”, Southeast Asian countries are bearing the brunt, facing a crisis of slashed healthcare budgets and stalled public health programs.

Countries like Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are seeing disruptions in vaccinations, infectious disease control (such as tuberculosis and AIDS), maternal-child healthcare, rural clinics and health education.

Hundreds of millions of aids slashed, who can these countries turn to? Or can ASEAN break the cycle of dependency and become self-reliant?

Adrian Pereira, the executive director and co-founder at North-South Initiative (NSI), a Malaysia-based organization dedicated to advancing human rights and social justice causes helping migrants and refugees, finds it hard to say no.

“We simply can’t tell vulnerable people that we can’t help them. It’s impossible to say that,” said Pereira.

Although NSI doesn’t directly receive funds from USAID, global aid cuts have created a ripple effect, causing the organization to lose about 40 percent of its donations.

“We run large programs to help migrants, refugees, and non-citizens in Malaysia. Some are HIV or AIDS patients. Now, we can’t even provide basic medical care—this is sad,” he said.

As of July 1, 2024 (U.S. time), USAID—founded in 1961—was officially shut down, ending all foreign aid operations.

Some projects aligned with Trump-era policies were transferred to the State Department. Even earlier, Trump signed an executive order to begin U.S. withdrawal from the WHO, leaving it with a massive budget shortfall.

Pereira revealed that NSI had written to the Ministry of Finance for support two years ago, but never received a response.

As donations plummeted, staff had to dip into personal savings or borrow from family to keep humanitarian services running.

“We don’t want to rely on foreign funds forever, but the Malaysian government offers no financial support to small and mid-sized NGOs focused on migrant and human rights. We can only rely on charity and overseas aid,” he said.

The U.S. is the world’s largest donor of foreign aid. According to ForeignAssistance.gov, USAID allocated USD 837 million to eight ASEAN countries in 2024.

Top recipients include Myanmar ($238M), Indonesia ($151M), Vietnam ($135M), and Thailand ($20.45M). Wealthier countries like Singapore and Brunei were excluded.

Indonesia, ASEAN’s largest economy, has implemented over 400 USAID-backed projects, particularly in eliminating tuberculosis and AIDS. In 2023, TB overtook COVID-19 as the deadliest infectious disease in the country.

Indonesia’s 400 Projects Now Uncertain

Previously, USAID had agreed to extend its bilateral cooperation with Indonesia until September 2026, including an additional $150M investment—now, all up in the air.

Philippines organizations seek new funds

In the Philippines, USAID cuts pose a threat to rising HIV infections. LGBTQ+ rights organizations are urgently seeking new financing strategies and donors.

Landmine-clearing project in Vietnam halted

Vietnam had to halt a rehabilitation and unexploded ordnance (UXO) clearance project for war victims.

Various sectors in Cambodia impacted

In Cambodia, agriculture, health, and mining projects are expected to suffer major impacts—possibly turning to other nations for help.

Malaysian refugee agencies on the brink of closure

In Malaysia, long-time humanitarian organizations serving vulnerable groups are also struggling. Refugee aid agencies face possible closure, and even the most basic and essential healthcare services are being cut.

Humanitarian medical services cease at Thai-Myanmar border

Many organizations stationed at the Thai-Myanmar border have announced the end of humanitarian medical services, leaving pregnant women and oxygen-dependent patients without access to essential treatment and medication.

Earlier this year, following the U.S.’s drastic budget cuts, countries like the UK, Belgium, France, Germany, Sweden, and the Netherlands also slashed their aid—signaling a large-scale Western donor retreat, especially among NATO members reallocating funds to defense spending.

Alongside slashed foreign aid, rising tariffs have pushed up prices of medicines, vaccines, and medical equipment.

Bulk purchase to lower cost

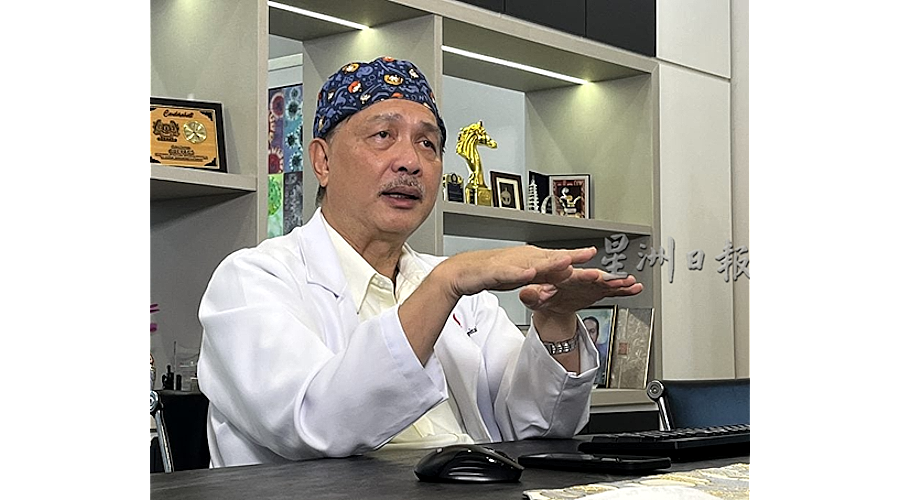

Former director-general of Ministry of Health in Malaysia, Tan Sri Dr. Noor Hisham Abdullah suggested Southeast Asian nations to find ways for lower procurement costs—like pooling resources through ASEAN and negotiating bulk purchases for better prices and maximum efficiency.

During the COVID-19 crisis, Noor Hisham, who was the director-general of Health Ministry then, recalled ordering its first vaccine batch from a U.S. pharmaceutical company for its 30+ million population in December 2020. The price was high and it took six months to arrive.

“Compare that with the EU—30 countries ordered together, got lower prices and faster deliveries. That’s the power of scale.

“We could join with other ASEAN countries—especially for expensive medicines. Bigger orders mean better negotiating power with pharmaceutical companies,” he said.

With a combined population nearing 700 million, ASEAN (with Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand alone exceeding 300 million) could greatly enhance its bargaining position through joint procurement.

Medical tourism a great potential for Malaysia

Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand have made significant strides in medical advancements. Thanks to low costs and high quality, the region is a hub for medical tourism.

In 2023, the revenue for medical tourism in Malaysia exceeded RM2 billion—indicating vast market potential.

Now the chairman of UCSI Healthcare Group, Noor Hisham believes Malaysia can develop its own medical device manufacturing sector with foreign investment, turning the country into a production and export hub—driven largely by private hospitals.

“Many government hospitals are already overburdened. The involvement of private sector can ease the load, establish training centers, attract international students, and boost the economy in Malaysia,” he said.

Chris Humphrey, the executive director of the EU-ASEAN Business Council, also welcomed medical tourism as a promising industry for developing countries.

It draws patients who are willing to pay for medical treatments and the revenue can be reinvested in local healthcare infrastructure—reducing costs overall.

WHO data shows that per capita healthcare spending in Southeast Asia rose in 2022 compared to 2019, covering primary care and rehabilitation.

Singapore tops the list ($4,321), followed by Brunei ($666), Malaysia ($458), and Thailand ($370)—countries with relatively well-established healthcare systems.

What’s more telling is out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure rates: Myanmar (65.1 percent), Cambodia (61.2 percent), Philippines (44.6 percent)—meaning citizens often pay for healthcare themselves.

“The higher the OOP rate, the more dangerous it is,” Noor Hisham warned. “It means people must spend most of their money on healthcare when they fall sick.”

The OOP rates in Malaysia and Vietnam stand at 37.9 percent and 39.5 percent respectively. In contrast, Brunei, Thailand, and Singapore have much lower rates: 7.7 percent, 9.2 percent, and 24.7 percent.

With global healthcare costs rising, prevention is critical for developing countries in Southeast Asia, where resources are tight.

Chris Humphrey noted that most ASEAN nations still focus heavily on curative care—intervening after illness strikes—instead of prevention.

“Preventive care reduces the need for expensive treatments, allowing more resources to reach patients who truly need care. It makes better economic sense long term,” said Humphrey.

Noor Hisham agreed with Humphrey that developing and poorer nations must focus on primary healthcare, not secondary or tertiary care. Primary healthcare addresses most health needs and eases hospital overcrowding.

Change of mindset : preventive culture in Southeast Asia

In an interview with Sin Chew Daily, Humphrey stressed that Southeast Asia must change its mindset and prioritize prevention.

With aging populations, demand for healthcare will rise and could overwhelm national systems.

While Southeast Asia still has a generally young population—especially in Vietnam and the Philippines—Singapore, Malaysia, and Thailand are aging at various rates.

“If people learn the importance of prevention and self-care early, they’ll know how to handle minor health issues themselves. Empowering pharmacists to offer advice can ease pressure on frontline services.”

EU can’t fill the USAID void alone, public-private partnerships underway

Facing massive USAID cuts, Humphrey said the EU alone cannot fully cover the funding gap.

“But I believe the EU will try its best, alongside other partners and member states, to bridge part of the gap.”

He added that the EU-ASEAN Business Council is actively exploring public-private partnerships (PPP) to continue health projects previously supported by USAID.

“Formal EU-ASEAN collaboration on healthcare is still limited, but many European companies are already working with Southeast Asian governments—educating communities about health literacy and disease prevention,” Humphrey said.

Some companies specialize in diagnostics and are collaborating with ASEAN governments to promote early screenings for diseases like breast and cervical cancer.

Technology can help, telemedicine and e-pharmacy for remote areas

Southeast Asia houses a quarter of the world’s population. According to the World Bank, over half live in remote areas—some need to walk the whole day, crossing mountains just to reach a clinic.

These rural areas often lack food, clean water, education, and connectivity. Humphrey believes technology can bridge the healthcare divide—by using mobile phones for remote consultations.

“We can even use e-pharmacy to deliver medication to impoverished areas—integrating vulnerable communities into national healthcare systems.”

But this requires governments to invest more funds and show real political will.

European businesses are ready to contribute more in healthcare, Humphrey said.

The key is whether ASEAN governments are willing to work together and create mutually beneficial healthcare plans that serve the people.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT