In an era of shifting global power dynamics, the official launch of Malaysia’s Action Plan on Preventing and Countering Violent Extremism (MyPCVE) is both timely and commendable.

Policy-makers rightly acknowledge that the nation’s strategic location in Southeast Asia, coupled with evolving threats, can be exploited by violent extremism and terrorism (VE&T) actors.

They also recognize that MyPCVE aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reinforcing the Madani administration’s sustainability agenda.

Yet, beyond these commendable efforts, there remain critical gaps in national development that a truly robust P/CVE framework could help bridge—gaps that, if ignored, may undermine not only Malaysia’s broader security but also its long-term progress.

Approaching P/CVE with a broader, more integrated perspective offers a strategic opportunity to tackle multiple systemic challenges at once, extending the plan’s impact well beyond security concerns.

Earlier, based on systematic analysis, EMIR Research has defined what a truly robust P/CVE framework entails (refer to “Closing the gaps: Comprehensive P/CVE toolbox” and “From checklists to impact: Strengthening MyPCVE with evidence & expertise”).

While MyPCVE seems to focus primarily on prevention and a select few aspects of recovery, EMIR Research’s analysis (Closing the gaps: Comprehensive P/CVE toolbox) demonstrated that a more comprehensive, end-to-end response to VE&T must include comprehensive Prevention, Detection, Preparedness, Recovery, and Adaptation—reinforced by expert-led standardization, professionalization, a dedicated research consortium, and the IOOI methodology to ensure measurable, long-term impact.

VE&T is a progressive phenomenon that typically evolves in stages, with the risk to society escalating significantly at each step.

If we fail to detect and disrupt it early on—or neglect to establish robust mechanisms for controlling it later—the consequences can grow exponentially: more victims, deeper trauma, and greater damage to national assets.

It is, therefore, critical that P/CVE strategies incorporate adequate preparedness, intervention, and societal recovery measures.

Despite these urgent needs, MyPCVE as it currently stands gives the impression that it is still a “low priority item” for our policy-makers.

This is a dangerous misconception and a strategic oversight. Indeed, beyond geopolitical risks or ticking SDG boxes, a fortified MyPCVE is pivotal for the very fabric of Malaysia’s National Security.

However, it is also a unique opportunity to address other profound systemic weaknesses that threaten our resilience as a nation.

MyPCVE itself identifies “Insufficient inter-agency coordination” as a key challenge, citing overlapping programs and fragmented communication among multiple agencies and ministries.

Yet, the plan offers no added clarity on how to strengthen this inter-agency cooperation, as EMIR Research analyzed in detail in “From checklists to impact: Strengthening MyPCVE with evidence & expertise.”

Even more bewilderingly, despite acknowledging the glaring lack of systemwide synergy and failing to address it through current initiatives, MyPCVE suggests “reusing existing structures.”

This might superficially mirror another common trend among advanced countries (particularly Scandinavian)—to intentionally avoid creating new agencies solely for P/CVE—to prevent redundancy.

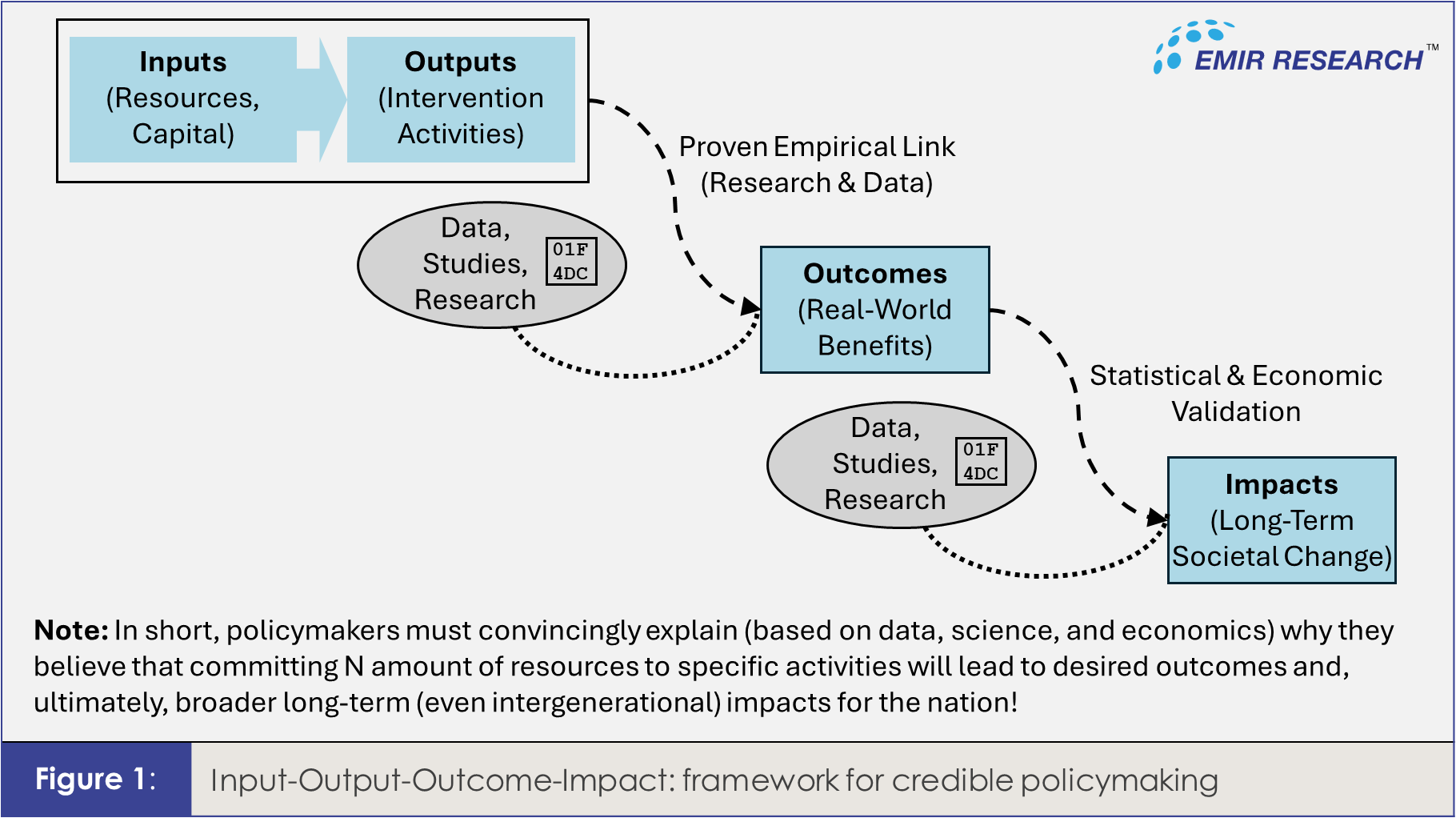

However, the critical caveat is that these nations already boast exceptionally robust governance and coordination systems, including the widespread institutionalization of the Input-Output-Outcome-Impact (IOOI) approach to ensure that public funds deliver measurable results (Figure 1).

In contrast, Malaysia lacks equally strong frameworks, making the intent to “reuse existing structures” even more concerning, especially when public funds continue to flow into MyPCVE, which remains overly focused on activity-driven KPIs—counting workshops held, programs launched, funds spent, instruments created or, sometimes, even vague “activities” as outcomes (“From checklists to impact: Strengthening MyPCVE with evidence & expertise”).

Funding counter-VE&T measures is a significant challenge, even in countries with stronger governance systems.

Sweden, for example, discovered that some civil society grants had been misappropriated by anti-democratic or extremist-linked organizations (Government of Sweden, 2023).

For Malaysia, where oversight is more fragmented, the only credible path forward is to institutionalize the IOOI approach, backed by rigorous professionalization of P/CVE, standardization of processes, and data-driven evaluations.

Therefore, MyPCVE’s current misguided “reuse” approach overlooks the need for a truly comprehensive, results-oriented strategy.

Instead, developing a robust MyPCVE should be viewed as an opportunity—or catalyst—to institutionalize critical structural changes in governance, coordination, and accountability systems.

Once established, these systems can (and indeed should) be replicated or reused to address other pressing national challenges.

After all, P/CVE itself is undeniably a matter of national security and cannot be relegated to a lower policy priority simply because Malaysia has historically enjoyed relative peace.

Addressing MyPCVE’s coordination gaps requires more than occasional meetings or ad hoc committees.

It demands a structural solution that fosters real-time information sharing, rapid learning, and consistent professional standards across all agencies and partners.

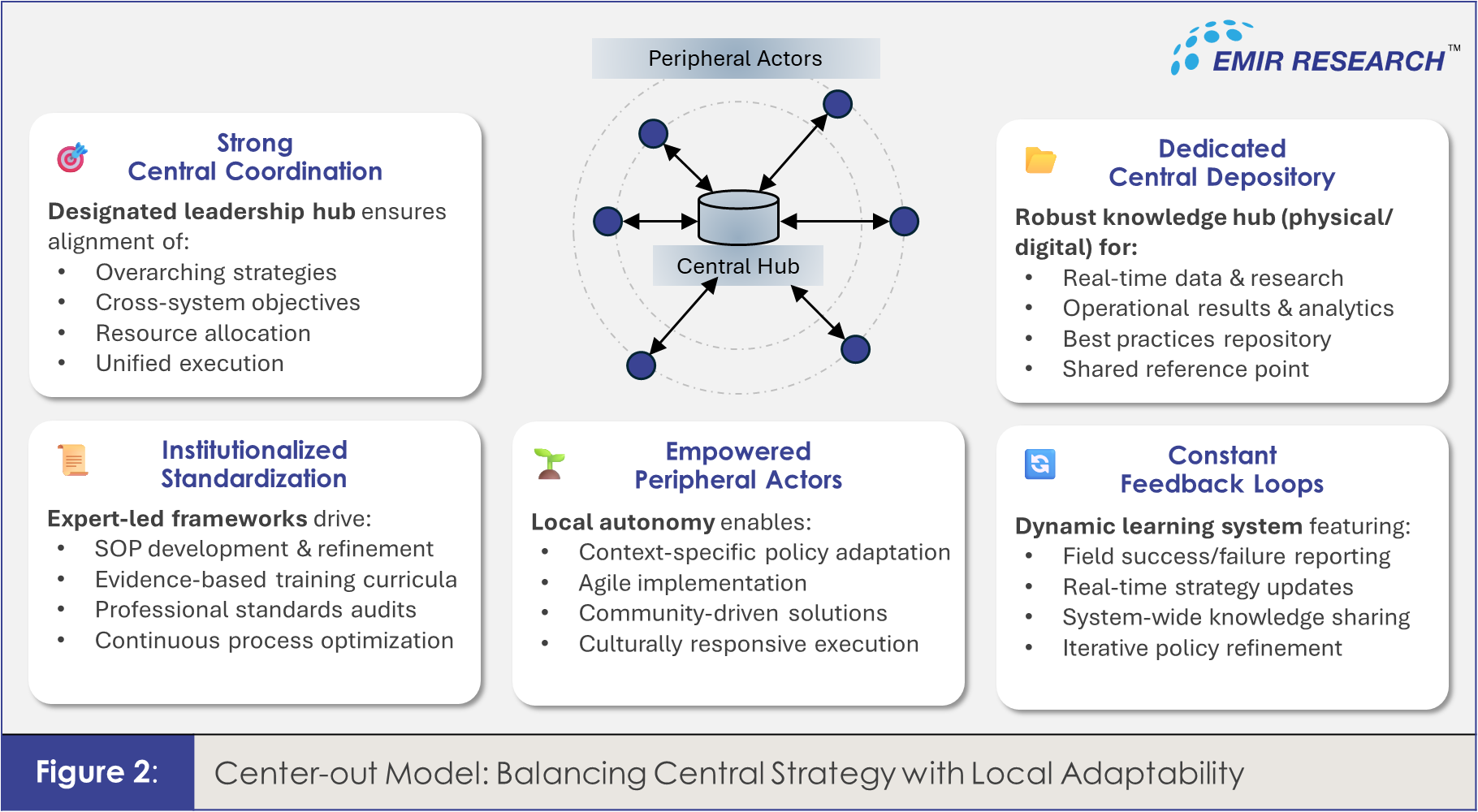

One compelling blueprint is the center-out approach, a governance model successfully employed in high-uncertainty fields like crisis response and corporate innovation (Kim & Spear, 2013).

Rather than relying on a rigid, top-down hierarchy, the center-out approach establishes a “central hub” (for instance, a dedicated P/CVE coordination council) that aligns national-level strategies, resources, and standards.

It then empowers “outer rings”—community groups, civil society organizations, and local authorities—to adapt these guidelines to their specific needs while maintaining feedback loops to the center.

The center, in turn, synthesizes on-the-ground data, research, and outcomes to continually refine best practices, policies, and SOPs.

This constant exchange forms a virtuous cycle of iterative learning, enabling rapid adaptation against VE&T threats that evolve in real time (Figure 2).

By integrating center-out principles, Malaysia would not only enhance MyPCVE’s effectiveness but also create a governance model that could be adapted to other urgent challenges—whether natural disasters, pandemics, or other high-velocity phenomena.

Coordinated responses become nimbler and more informed, making the country more resilient across the board

P/CVE is also deeply intertwined with a range of chronic problems in Malaysia, such as an inadequate social safety net, brain drain, youth unemployment, mental health issues, refugee management and even identity politics.

For instance, a strong P/CVE approach mandates holistic reintegration, yet we struggle even to address homelessness.

In many Scandinavian countries, “housing first” policies are integral to social services and are part of how they build resilience.

Therefore, a genuine P/CVE effort in Malaysia can only succeed if it goes hand-in-hand with solving other systemic social problems genuinely.

Furthermore, strengthening P/CVE governance, research, and professional standards not only heightens security but also generates better social policies.

Because violent extremism often feeds on vulnerabilities of all sorts, rigorous data-driven P/CVE research can reveal these overlooked problems.

By systematically addressing the root causes uncovered through P/CVE initiatives, Malaysia simultaneously advances broader development goals—reducing inequality, improving education, and fostering inclusive economic growth.

Another critical dimension: modern P/CVE relies heavily on data and digitalization.

Currently, we invest substantial resources in data centers and AI strategies but ironically overlook a low-hanging fruit strategy, where the government could become a major client for advanced AI tools in P/CVE.

In leading AI nations, public agencies often spearhead the adoption of AI for early threat detection, social media monitoring, or advanced analytics—subsequently benefiting both national security and broader digital transformation goals.

In short, establishing a comprehensive and robust P/CVE strategy that engages all available tools and fully addresses the progression of VE&T threats is not an overreach—quite the opposite.

Many P/CVE measures overlap with other core public services, such as disaster preparedness, community resilience, and mental health support.

Capitalising on these synergies boosts cost-efficiency while building a more cohesive and responsive society overall.

For these reasons, MyPCVE should not be treated as a mere footnote or a low-priority task. In strengthening Malaysia’s capacity to prevent—and, when necessary, respond to—violent extremism, we also strengthen the nation’s broader social fabric and institutional framework, creating a safer, more unified environment for MANY.

(Dr Rais Hussin is the Founder of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT