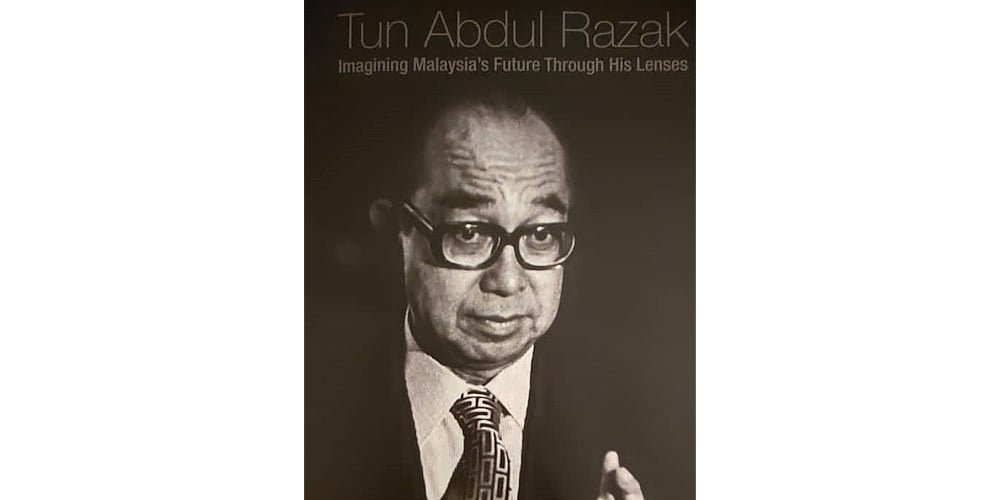

Anyone who approaches “Tun Abdul Razak: Imagining Malaysia’s future through his lenses” is bound to come away disappointed. Why?

While there are biographical and chronological details of Tun Abdul Razak’s tenure as the second Prime Minister of Malaysia (1970-1976), not excluding his tenure from 1957 to 1970 as the Deputy Prime Minister to Tunku Abdul Rahman, the first Prime Minister of Malaysia, that’s all that the book can share.

Spanning 365 pages, this book is nothing but tremendously impressive, though.

Except three chapters that merely touched the surface of the subject of Federalism, Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) and the negligence of Peninsula Malaysia on the welfare of Sabah and Sarawak, all remaining eleven chapters were tremendously mesmerising. How?

Starting from the Foreword, which was written in exquisite prose, Raja Rasiah explained that “this was (a book) borne out of concern that Tan Sri Kamal Salih, Datuk Professor Rahman Embong, Tan Sri Nazir Razak, Mohammad Tawfik Ismail” were concerned with the direction of the Malaysian government since 2010.

While Mohammad Tawfik Ismail, the son of the late Tun Dr Ismail Rahman, did not contribute a chapter, it was obvious that he had done his part as a scrupulous editor too.

Astoundingly the book has 33 sets of the latest figures to benchmark Malaysia to key metrics that measure economic development of the developed world, coupled with another twenty-five tables on some of the most important statistics in Malaysia.

Among others they range from “Self Sufficiency Rates, Key Food Commodities, Malaysia, 2018-2022,”; “Targeted Self- Sufficiency Rates, Malaysia, 2025-2030 percent,” and Shortcomings of Malaysia’s TVET, 2023.” too.

A serious Malaysian specialist should be able to read the book in less than 4 hours as each page tells a very structured and systematic manner by which the likes of Tun Razak and some of his closest friends – such as Tun Ismail Ali, Musa Hitam and Zain Azrai – kept coming up with one social economic plan after the other, especially after the May 13 ethnic riots in 1969, to steer Malaysia back into the right direction.

At the core of it was not merely a reference to the National Economic Program (NEP), which was supposed to be race-blind, indeed, to run from 1970 to 1990, but entities such as State Economic Developments Corperations (SEDCs) that were allowed to plant their roots in various states that formed Malaysia.

Reading the book, one cannot stop but be awed by the rigor that was put into the book by Rajah Rasiah especially.

Single-handedly, Rajah Rasiah contributed five out of the fourteen chapters.

However, it is worth mentioning that Tun Abdul Razak’s tenure as a Prime Minister while short, his dedication to serving Malaysia was long in coming.

Between 1957 and 1970, he had created the Malaysian Industrial Finance (MIDF) in 1960; the Malaysian Industrial Estates Limited (MIEL) in 1964; the Malaysian International Shipping Corporation (MISC) in 1968; the Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI) in 1969; Tabung Haji in 1969; the Malaysian Rubber Development Corporation (MARDEC) in 1969; the Malaysian National Insurance Berhad (MNIB) in 1971; not to mention MARA Junior College; Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) in 1970 (see pages 109-110).

What made the book an absolute joy to read was the passion of the authors themselves, not merely to celebrate the legacy of Tun Abdul Razak, but to chime in their own thoughts that a new and dynamic Malaysia is still within grasp.

In Chapter 1, Rajah Rasiah affirmed that “building a better future for Malaysia must address the trend of fall in the government revenue in the face of worsening debt” (page 15).

In Chapter 2, Abdul Rahman Embong, after explaining the latest dynamics in the last general election in connection in November 19 2022, ended his contribution by asserting: “just like the Rukun Negara (coined by Tun Abdul Razak) the concepts of Malaysia Madani and Bangsa Malaysia are non-partisan and non-sectarian and should not be politicised” (page 45).

In footnote 5, Rahman Embong also sniped at the flaws of Mahathir, who time and again, has always accredited Tun Razak as his mentor, which Rahman Embong clearly disagrees.

In Chapter 3, Nazir Razak, the youngest son of Tun Razak, who was barely 9, when his father passed on in 1976, spoke of the importance of involving various stake holders to make the good decisions under the system of “deliberative economy” (page 67).

In the following Chapter 4, Kamal Salih spoke of NEP’s original 50-50 proposition of splitting the national wealth.

He also warned of the “Dutch Disease,” or the resource curve of trying to sit on the wealth of the countryside without going into Science, Technology and Investment (STI).

In between, the other chapters that were most intriguing were Chapter 9 by Naguib Mohammad Nor, Rajah Rasiah and Kamurul Azman Muhammad.

Together the trio map out in elaborate details our vulnerabilities to various kinds of vegetables especially mangoes (See page 219-222).

It is not the place of this book review to go through every chapter. But when one fast forward to Chapter 12, the contribution of Anis Yusal Yusoff is just as meaningful on other chapters on Artificial intelligence and Technical Vocational Education Training (TVET).

In Chapter 12, Anis explained the strictness by which Tun Razak handled corruption.

More importantly this chapter also touched on the existence of the “Special Cabinet Committee on Anti-Corruption and National Centre for Governance, Integrity and Anti-Corruption.”

Unless the country is backed by a strong political will, Malaysia cannot throw away the yoke of corruption that has been a blight on Malaysia both economically and financially (see pages 303-304).

Indeed, the mere effort to “communicating messages across the government and the grassroots is essential” (See page 316).

This book is also exceptional in terms of introducing the lay reader of His Royal Highness Sultan Nazrin Shah on two books he has written. Therein “Charting the Economy: Early 20th Century Malaya and Contemporary Malaysian Contracts” and “Striving for Inclusive Developments: From Pangkor to a Modern Malaysian State,” both of which were by Oxford University Press in 2017 and 2020 respectively.

All said, the book has to be read in full to appreciate the beauty of the scholarship and craftsmanship put into making it one of the best books on modern Malaysian history and developments to come.

While this review has taken a positive note, the fact of the matter is Malaysia is reeling from many dark matters, potentially, decay, all of which are fleshed out in the book.

Whether it is a soft or hard copy, it is a must by from the Asia Europe Institute (AEI) in University of Malaya or any bookshops in Malaysia or abroad.

(Prof Dr Phar Kim Beng is Expert Committee Member of the Centre of Regional Strategic Studies, CROSS, and Professor of ASEAN Studies at ISTAC-IIUM.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT