Just four days after the 47th American president moves into the White House in 2025, a pair of VIPs from China will begin receiving a stream of excited visitors.

The much-awaited debut of the giant pandas on Jan 24 at Washington’s Smithsonian National Zoo, where they are now under quarantine, could hardly be timed better.

The furry emblems of China’s soft power have charmed Americans since the Nixon years, but the bar is higher for the guileless Bao Li and Qing Bao.

The relationship between the two great powers has frayed to the point of breakage. And most of their Asian partners, bound to both countries through trade and security, wonder if it is all only downhill from now.

Expectations are low, no matter who wins the deadlocked Nov 5 election, but it would seem that Asia cautiously views Vice-President Kamala Harris as the better option.

Former president Donald Trump’s second stint could come with massive tariff hikes and another trade war, with severe consequences for China-centric manufacturing networks across Asia.

His wish for a weaker US dollar could weaken Southeast Asian exports.

And the pressure on Asean nations to choose sides in the China-US rivalry could escalate quickly as Trump prioritises competition with China.

Harris may walk further along the more predictable path laid by President Joe Biden.

She will likely target for sanctions on a select, but growing, number of industries deemed critical to US economic security.

Her consultative, multilateral approach will at least feel less abrasive.

But neither candidate packs policies that can be viewed as ideal, said Asian and American officials, diplomats, businesses and think-tankers in interviews with The Straits Times.

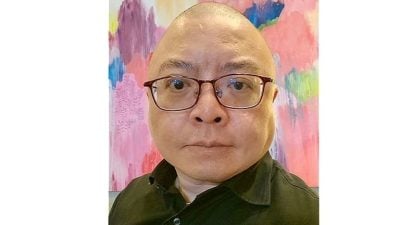

Many would agree with Malaysia’s Deputy Investment, Trade and Industry Minister Liew Chin Tong’s assessment that the difference between Harris and Trump is a matter “not of direction, but intensity”.

Neither can turn back the clock to a simpler, unipolar world.

“Trump will definitely take a far more isolationist and America First approach, but it doesn’t mean Harris will be able to take the world back to 1995 when WTO was formed,” Liew said, referring to the hopes spurred for a reduction of trade barriers and expansion of global trade at the birth of the World Trade Organisation.

If there is no big crisis, then Southeast Asian countries will probably get on with Trump 2.0 with a grimace, said Greg Poling from Washington’s Centre for Strategic and International Studies.

“They will get through without too much disruption, which is what happened the last time. But there might be a souring of sentiment towards the US, a double-digit drop in trust in US leadership. And the US government will find it harder to get public or diplomatic support for initiatives,” he added.

Singapore’s Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan put it pragmatically while speaking to the media after attending the UN General Assembly in New York in September.

“We will deal with the consequences of elections, and we will engage whoever is victorious,” he said.

Could Trump make a breakthrough with Xi?

With diplomatic decorum, the Chinese Embassy in Washington said it hoped that whoever is elected is committed to growing ties. The furry emissaries may help, it ventured.

“We hope the arrival of the pandas will inject fresh impetus into exchanges between China and the US, and help stabilise the broader bilateral relationship as well,” said embassy spokesman Liu Pengyu, ascribing the timing of the duo’s arrival to discussions between the American zoo and Chinese conservation officials.

But from Beijing’s perspective, scholars who engage in Track 2 diplomacy on behalf of the state have been unusually public in hinting at a preference for Harris.

China sees her continuing Biden’s policy of engagement and worries that people-to-people exchanges will snap if Trump were to become president, said Professor Jia Qingguo from Peking University and Professor Chen Dongxiao, who heads the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies.

But others, like Professor Da Wei from Tsinghua University, caution that policy continuity is less positive than it seems because it perpetuates poor ties that exist now.

Trump’s presence may bring unexpected benefits for China, he added.

“If Trump were to continue with the tariffs, it may reach a point where the American economy cannot bear it any more, and Trump’s new ideas on foreign policy issues, such as on Ukraine, may bring about new opportunities for us.”

If Trump ends US support for Ukraine and retreats from the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, it could create a power vacuum in Europe that China might seek to fill through increased diplomatic and economic engagement.

A wilder version of this argument goes thus: Trump would be good for China because Trump is bad for America’s democracy, economy and allies.

On social media, he is jokingly called “Chuan Jian Guo” or Trump the Nation Builder, with the nation here being China.

An intriguing proposition is whether there could be an unexpected breakthrough under the unpredictable Trump, who positions himself as a dealmaker.

Poling said: “I would imagine that Trump would be open to some kind of splashy but somewhat shallow displays of diplomacy, as we saw under the first term.”

But it would be unsustainable because Trump is committed to beating China economically, he added.

A defining moment could be how Trump handles Taiwan relations early in his administration.

After winning the 2016 presidential election, he breached decades of diplomatic protocol by having a phone conversation with Taiwan’s then President Tsai Ing-wen.

Since the US switched diplomatic relations to Beijing in 1979, there had not been an American presidential phone call to the president of Taiwan.

The incident drew a critical but relatively low-key response from Beijing, which maintains that Taiwan, which is self-governing, is part of its territory.

China might take a more aggressive stance on the flashpoint issue now; after meeting Biden in San Francisco in November 2023, Chinese President Xi Jinping said Taiwan is “the first red line that must not be crossed in China-US relations”.

Trump has framed the issue of defending Taiwan in transactional terms, suggesting that support would depend on whether it would be economically beneficial to the US, and criticising Taiwan’s semiconductor industry for allegedly taking “about 100 per cent of our chip business”.

“It is possible that Trump would view it as leverage over Xi and would want to act tough on Taiwan. But it is also possible that he would be willing to sacrifice Taiwan in bilateral accommodation with China,” said Poling.

Harris is expected to continue current policies but, unlike Biden, she has not explicitly stated that the US would intervene militarily if China were to attack Taiwan.

As for the two US allies in East Asia, Trump 2.0 may trigger some bad memories.

In his first term, Trump caused friction when he pressed Japan and South Korea to increase their financial contributions for hosting US troops, a demand that might be revived.

Observers in Seoul point to a striking difference between Harris, who has been silent on Korean peninsula issues on the campaign trail, and Trump’s repeated references that “things can happen” in his negotiations with North Korea, hinting at the potential for renewed dialogue with leader Kim Jong Un.

Trump was the first US president to set foot inside North Korea in 2019.

“If Trump gets re-elected and withdraws American troops, South Korea will have to move towards having nuclear capability,” said one analyst, speaking off the record to discuss a sensitive issue.

South Korea does not currently possess nuclear weapons, but is concerned about the US rolling back its nuclear umbrella under Trump, even as it faces nuclear threats from North Korea.

Japan has had a better record with Trump, thanks to the personal rapport that the late prime minister Shinzo Abe struck with him, even before Trump’s 2017 inauguration.

Even so, tentativeness remains about a possible Trump return. Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba has said he was not averse to taking a cue from Abe’s diplomatic gambit, but he is now battling to stay in power after his coalition lost its majority in the Oct 27 General Election.

Harris, on the other hand, can be expected to reinforce ties, like Biden did with a historic trilateral summit with Japan and South Korea at Camp David in August 2023.

He also elevated the strategic Quad alliance between the US, Japan, India and Australia.

Professor Satoru Mori from Keio University, speaking at the Foreign Press Centre of Japan on Oct 11, said: “Some people are worried that Trump might scuttle these frameworks. But Quad was originally conceived during the Trump administration. And US-Japan-South Korea could be considered as an instrument to pressure North Korea.”

Dr Lynn Kuok, the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asia Studies at the Brookings Institution, suggested that the differences between a Trump and Harris administration are likely overstated in the security realm.

“Although former president Trump is often accused of being dismissive of alliances, and we might see him revert to his more transactional instincts, a more hawkish Trump 2.0 would ultimately seek to deepen security and economic ties with important allies and partners so as to better counter China,” she said.

Outside of East Asia, there is less anxiety.

Both India and the Philippines appear confident that their ties with the US post-Biden will continue to flourish, no matter who is in the White House.

Manila expects a Harris administration to continue upholding Biden’s vow to defend the Philippines from any attack in the South China Sea, under their mutual defence treaty.

“We also expect continued assistance in our defence modernisation through increased foreign military financing, as well as in rallying like-minded countries to support the Philippines in pushing back against China’s illegal, coercive, aggressive and deceptive actions in the West Philippine Sea,” said Philippine Ambassador to the US Jose Manuel Romualdez, using the Philippines’ term for the part of the South China Sea within its exclusive economic zone, much of which is also claimed by the Chinese.

He said he had been assured that support for the Philippines will not change under Trump, although the approach might.

“The emphasis on the networks of alliances and partnerships may not be as pronounced under Trump. But he could be more forceful and decisive in his words and actions against China and in support of the Philippines,” he added.

Poling was more sceptical.

“If there was a real crisis, people would be much more sceptical of his willingness to follow through, to put American skin in the game to fulfil alliance commitments or deter China.”

India appears better placed to weather the changing of the guard. It is expected to remain a key part of the American Indo-Pacific policy and as a bulwark against China.

Its External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar said in August that India will be able to work with the US president, “whoever he or she will be”.

There is virtually no difference, agreed Poling. “Even though there might be some cachet in Harris being the first president of South Asian descent in the US, Trump is also wildly popular, at least with Modi and his government.”

Given the stresses associated with the return of Trump, it is understandable why Asia might prefer the continuity under Harris, although her administration may extend US support for Israel in the bloody Gaza war, which has been condemned by large Muslim populations across the region.

She may not have “the experience or the desire to quickly shape her foreign policy in ways that are significantly different from Biden’s priorities”, noted Malaysian Investment Development Authority board member Ong Kian Ming.

But he added: “This should be a reassuring point for Asean countries in being able to anticipate continuity, even in areas which we are not in agreement with, for example, Gaza, compared with the kinds of uncertainty under Trump, for example, stopping military aid to Ukraine.”

Will US businesses fight against tariffs?

Trump says his “beautiful” tariffs – a 60 per cent tariff on goods from China and up to 20 per cent on everything else the US imports – will be good for the economy, but corporate America would likely disagree.

“If you are in the twisting wire hangers business, you might be pretty happy. But in terms of growth and employment, there is nothing to be said for it,” said a senior business source based in Washington, pointing out that if manufacturers were forced to source everything domestically, it would make the US completely uncompetitive.

But businesses are preparing to push back, counting on the fact that the narrative on Capitol Hill has changed since the first Trump term, when the usually pro-trade Republicans had stayed silent as debates raged on bilateral trade deficits.

“I am not sure that there will be as much enthusiasm for tariffs as a tool to manage debt and trade deficits,” said the business leader.

“It is very possible that the Trump conversation shifts to one that is about economic security and less about the classic Trump approach to trade.”

Almost all Southeast Asian nations, particularly those with industries like textiles, electronics, automobiles and agriculture, could be particularly vulnerable to new US tariffs.

But countries like Vietnam may continue to benefit from trade diversion as companies with factories in China seek to diversify away from it to escape the hefty US import tariffs.

Wendy Cutler, vice-president of the Asia Society Policy Institute and former acting deputy US trade representative, said Trump is unlikely to heed any advice on tariffs.

“Should Trump win, our trading partners need to prepare for tariff hikes,” she said.

“While the timing, condition and level of increases remain unclear, there is no doubt that Trump remains the ‘tariff man’.”

But Dr Alicia Garcia Herrero, the Hong Kong-based chief economist for Asia-Pacific at French investment bank Natixis, said China may be able to dodge a bullet.

“Tariffs are a problem for China, but less than people think, because China will re-export through other places like Vietnam and Mexico to the US. Also, it will reroute its own capacity to what is today its largest export market, which is the European Union,” she said.

Trade has not been a priority issue for Harris, said Cutler, adding that the Vice-President would likely adopt Biden’s worker-centric policy.

The question that remains unanswered is to what extent Harris’ policies will depart from Biden’s.

Would she, for instance, add digital economy to the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, which was the Biden administration’s response to Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade pact in 2017? Could she strike more limited trade deals like mineral cooperation agreements?

These will all potentially benefit the region, where countries are embracing the digital economy and where several are rich in minerals.

Southeast Asia, meanwhile, has been working to diversify its economy to reduce overall dependence on any single market, including the US’.

Malaysia no longer looks to the US or Western markets as the final destination of exports, said its Deputy Investment, Trade and Industry Minister, Liew.

In 20 years, China and Southeast Asia will be the big consumers, not just export-led economies, he said.

And with multinational companies seeking to mitigate risks associated with trade tensions by relocating their operations and diversifying their supply chains, Malaysia is in a favourable position to act as a strategic intermediary, whether Trump or Harris wins, he said.

“Malaysia must take this opportunity, whether it is a very short window, or longer window, to make itself an indispensable part of the supply chain,” Liew said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT