Walking through the streets of Kuala Lumpur today reminds me semantically of how it is an example of the meeting place of two rivers converging at a muddy juncture—akin to the stream and union of cultural differences coming to terms in a globalised world—where throughout history these river networks allowed people to trade goods and cultures with one another in Malaysia.

As the time looms over the weekend of Merdeka and her colourful celebrations call for an important reflection of ourselves in these challenging, if not ‘interesting’ currents.

I always ask myself what national unity means in Malaysia. Is Malaysia a country perhaps without a nation?

We have our ‘Negaraku’ song but no folk songs to tie the diverse ethnicities of Malays, Chinese and Indians.

How about the 137 living languages, to name a few, of Jakun, Telugu to Iban of Sarawak exchanged within Malaysia and her fringes? They also deserve more recognition.

National unity, for me, in its heartiest essence means fostering a sense of belonging and a shared identity of dialogue in those communities, and above all, going beyond religious and cultural differences.

As history and memory recall, national unity goes back to the tragic events of 13 May 1969 of racial Sino-Malay tension.

The bad fortunes of the tension serve as a stark reminder for us today that history can repeat itself.

The good fortunes of the aftermath, however, are brought to us through the Rukun Negara of 31 August 1970. Its principles of belief in God, loyalty to King and country; the supremacy of the Constitution; the rule of law; and courtesy and morality serve as the basic foundation for fostering unity for each community and each individual.

Today, these Rukun Negara principles resonate strongly with the message of dignity for everyone, everywhere by Sultan Nazrin of Perak at the Human Dignity Conference from 6th to 7th August 2024, which I was fortunate to have attended.

Everyone deserves to be safe, respected, and included in a world where tolerance and inclusivity are lacking.

I saw the Sultan’s rallying call for togetherness stir an urgency in all the participants and, especially vibrant with, the National Unity Ministry and the MySDG Centre for Social Inclusion.

The Unity Ambassador Mrs Suraya Wen urged us to “instil our spirit of volunteerism to portray our awareness on respective roles and responsibilities in the community regardless of race and diverse backgrounds”.

So too, Dr Teo Lee Ken, assistant director to MySDG Centre for Social Inclusion addressed the issue of statelessness, particularly in Sabah, and how we should leave no one behind and address human challenges on the ground by building inclusive communities.

All the stakeholders from top to bottom, bridging theory and practice, reflect Malaysia’s ongoing efforts to build an inclusive and cohesive society where everyone’s dignity is to be upheld.

We should be proud of our success stories as the United Nations hails us as an example of success in maintaining a balance between our different ethnic groups and our diverse languages.

Our togetherness defines Malaysia’s tapestry of diversity against the world.

Even as I was reared in the UK, where diversity in the UK is celebrated but (often compartmentalised and) isolated within their own individual confines, I find Malaysia’s sense of pride and togetherness a palpable, communal, effort.

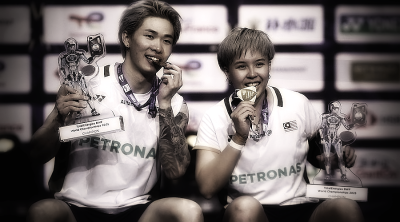

Testament during traditional festivities like Hari Raya, Thaipusam, the Hungry Ghost Festival, and even the Paris Olympics 2024 where the streets come alive with celebrations where communities share in one another’s joy—highlighting our global standard for unity amid diversity.

However, the road, or rather the progress to unity, is fraught with challenges.

Stereotypes and biases continue to create divisions and how we perceive one another, leading to misunderstandings.

For example, the Malays, due to the French word ‘malaise’ are inherently lazy; coincidently the opportunity gap left by them the Chinese are the most hardworking in society; and the Indians fill whatever secondary characteristics the Malays and Chinese lack.

I believe these tough questions of unity come down to how comfortable we are with the differences that we find in others.

What are the differences we should appreciate or set aside, connect or separate our experiences, and strengthen or weaken our bonds?

Due to these differences, the education system with its multiple streams has been criticised for sowing what Phillip Loh called “seeds of separation” (due to the British colonial policy of non-interference). That is, there is no single stream of education in Malaysia.

The government schools, along with Malay, Chinese and Tamil vernacular schools, created “a gulf that was linguistically separate and ethnically separate”.

Many Malaysian politicians like Khairy Jamaluddin and others felt that a single-stream education system was necessary to foster national unity and national identity.

Despite the challenges, there are success stories that offer hope.

In the past 20 years, the increasing enrolment in 2018 and still increasing, to 19 per cent of non-Chinese students in Chinese vernacular schools is one such example, Professor Danny Wong of Universiti Malaya stresses.

In Sabah, for example, the migration of some Chinese populations to urban centres leads to a vacuum of rural Chinese vernacular schools in some villages that have 80 per cent more non-Chinese students.

This trend reflects a growing acceptance of cultural differences and a desire to learn from one another. However, all sides need to give way for the betterment of the nation.

Ultimately, national unity in Malaysia is a dynamic, ongoing journey in the right direction. It still requires continuous, truly Madani civil and inclusive effort from all sectors of society to steer the course.

Rukun Negara provides a strong foundation that encompasses inter-generational connectivity. But the real work lies on ‘real’ political willpower and how Malaysians will engage with one another in everyday life.

I believe it is not about erasing differences but rather embracing them in a way that strengthens the fabric of society.

Malaysia’s journey towards unity offers valuable lessons on how to build a nation where everyone, everywhere–regardless of who he is–feels a true sense of belonging.

(Rafi’i al-Akiti is Cambridge PhD Student.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT