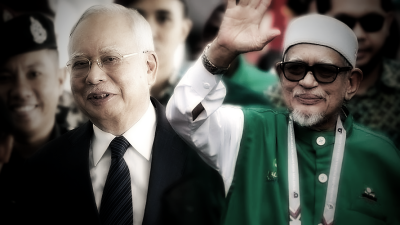

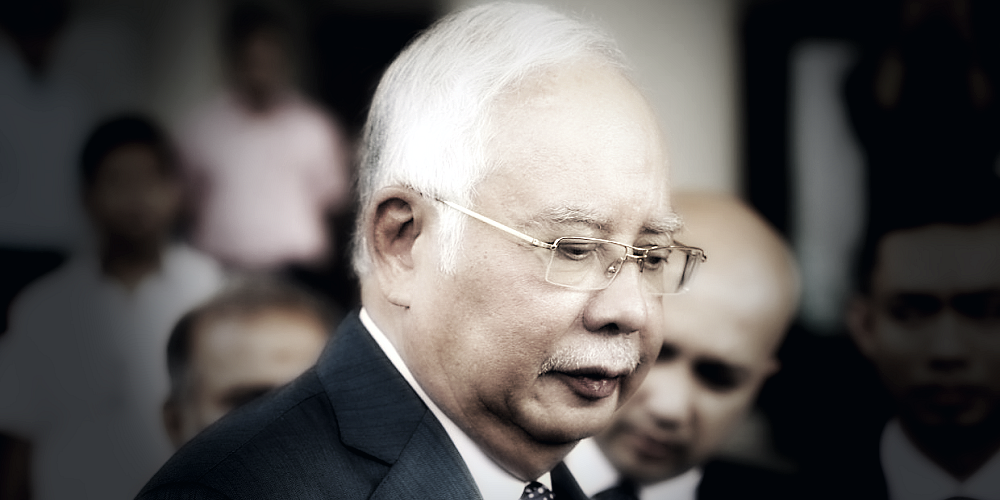

Najib might be in jail, but he could still command every Malaysians’ attention.

It is now official: The Pardons Board has decided to halve Najib’s sentence from 12 to six years and reduce his fine from RM210 million to RM50 million.

In Malaysia, the life of a politician is long. Nothing is really over until it is over. Not even prison for a corruption case. To some extent, enough voters allow for this.

Some diehards in Umno even want and celebrate Najib’s release. Though this is only one case out of the many that Najib still has to confront, including charges on abuse of power and money laundering relating to a RM2.6 billion 1MDB case, this partial pardon is bound to have significant implications to politics in the next few years.

For Najib and his diehard supporters: What he hopes for is a full royal pardon that would not only set him free but also allow him to run for elections again.

That did not happen.

Even though the official statement stated that Najib could be released on August 23, 2028, he could be out even earlier.

After completing one-third of his sentence, Najib could apply for parole for good behavior that could allow him to be released earlier — as early as two years earlier on August 23, 2026.

While some may think that is early enough for him to run for the next election, which will happen in November 2027 the latest, this is incorrect.

As the official statement did not make explicit mention of Najib’s five-year ban after his release, we should presume that Najib will not be able to run for any public office until at least August 23, 2031. That means Najib might miss one or more election cycles before he could be active again.

While he will be free in 2026 at the age of 72, he could only exercise any political influence as an MP in 2031, at the age of 78 — not too far away from the initial release date of August 23, 2034.

Of course, that does not mean that Najib could not plot a comeback within the party. He could still take over Zahid’s presidency and start packing the election candidates with his loyalists and act as the de facto decision-maker by bending others to his will.

Ultimately, however, politicians still operate through the public mandate — that is why non-MP ministers are still appointed as senators in the Parliament.

The time gap between his release to running for office is still long, and if other cases lengthen his sentence, the partial pardon may prove less useful than initially thought.

For Zahid Hamidi: Zahid’s primary interest is to hold the tricky balance of keeping the presidency to himself and satisfying Najib’s supporters.

While Zahid has always appeared as an ally to Najib, he does not want Najib’s influence to overshadow his. To this, he has promised to pursue the pardon for Najib the moment Najib was sentenced to jail.

Opponents of Najib have long been purged from the party.

With the partial pardon, Zahid could go to Umno and say that he has done his best, and the partial pardon was the result of his hard work.

How Najib’s diehards would take this is hard to say, but it is likely that they would accept this as a relief from a bleak campaign to free their Bossku.

For most Malaysians who are not from the elite, they could not be blamed for feeling that the world is not run on the concept of fairness.

For Anwar and PH: If the King’s decision was to pardon in some form or another, then a partial pardon is the best case Anwar and PH could get.

Of course, its best-case scenario is for the Pardons Board to reject Najib’s bid, but that is not within Anwar or PH’s decision to make.

A partial pardon is the best case because it still does not result in Najib’s freedom immediately. Najib is still serving his time for his crimes and PH could hope that six years still feels long enough to feel like justice is served.

At the same time, PH also knows that this would ensure Umno stays intact with the Unity Government and support its reforms.

But this will inevitably come at a cost.

Even though Anwar and PH did not decide the pardon, as it was within the royalty’s power, they will still take the blame that comes with it, as they are the face of the government.

Some may fault the coalition for not practicing the anti-corruption message it preaches, and some will also grow disillusioned to the point of choosing not to vote.

This decision will cost PH some votes. The only question is how much could PH afford to lose before it loses appeal to the progressives.

For the people: Beyond the issue of corruption, this has demonstrated a world of two divides.

To many, Najib could receive the sentence and fine discount because he represented an elite circle familiar to other decision-makers.

He comes from an established family and is seen by some to have done well in running the state and the country.

For most Malaysians who are not from the elite, they could not be blamed for feeling that the world is not run on the concept of fairness. It is run, ultimately, by power.

(James Chai is a Think Tank Chief Researcher and Legal Advisor)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT