When the new health minister Dr. Dzulkefly Ahmad called a press conference Monday evening, many Malaysians were not worried about the threat of Covid-19, but scared that MCOs would be reintroduced, once again devastating the livelihoods of many within the informal sector, leading to the “white flag movement” in 2020/21.

According to World Economics, the informal economy in Malaysia represents 25.3 percent of the country’s GDP, representing RM1,193.8 billion at GDP PPP levels.

Malaysia has the 6th largest informal economy as a percentage of GDP in the world, after Uzbekistan, Cyprus, Greece, Botswana and Costa Rica.

The Star reported informal sector employment at 3.5 million in 2021, contributing 23.2 percent of the nation’s employment.

The informal sector includes agricultural day workers, construction site workers, auto and motor repairers, gardeners and grass cutters, home construction workers, babysitters, and child minders, food hawkers, content writers, general labourers, cleaners, tailors, seamsters, market salespeople, food and beverage delivery riders, e-hailing drivers, lorry drivers, outsourced freelance workers such as internet salespeople, programmers, accounting and book-keepers.

According to the Department of Statistics, about 5 percent have no formal education, while most hold SPM-level qualifications. Some have degrees, where those with postgraduate qualifications rose 14 percent over 2021.

Median monthly income of those working in the informal sector was RM2,062, putting many families below the poverty line.

Informal sector major part of the Malaysian economy

Much of the work undertaken by people within the informal sector is invisible.

Even though the informal sector is a major part of the Malaysian economy contributing over 25 percent to GDP, it is rarely given the attention it deserves by policy-makers.

As was seen during the Covid-19 pandemic and MCOs, the informal sector is the most volatile sector of the Malaysian economy, where those within it are at the greatest risk of financial hardship in any downturn.

Yet, this sector is crucial to the Malaysian economy, and even the Malaysian way of life.

The informal sector is never usually seen as a driver of economic growth, and so suffers from lack of attention in terms of incentives and assistance.

That’s why the informal sector holds down GDP per capita to levels that keep Malaysians in the middle-income trap.

For the Malaysian economy to prosper, there must be a policy pivot towards the informal sector.

Fiscal like “Menu Ramlah” even hurt those in the informal sector.

Programs to assist SMEs are targeted at growing SMEs rather than the traditional informal sector businesses mentioned previously.

Poverty-eradication spending sometimes misses those engaged within the informal sector, and any universal welfare net is still just a “pipe dream” in Malaysia at present.

What can be done to support the informal sector?

The gig economy has often been glamorously portrayed as young skilled graduates doing freelance corporate IT work from home.

The reality is that most young graduates don’t have either the experience or connections to obtain such work.

Although the gig economy is claimed to be growing, majority of gig workers are semi-educated motorbike food and beverage delivery riders.

Even though they are freelance, there are time constraints on each delivery, putting them under tremendous pressure to complete their set responsibility by the e-food platforms. This leads to traffic dangers on most urban roads.

These types of jobs have a very high turnover, discourage many from taking up work again, and in the end go nowhere.

These jobs are at the bottom of the work “totem pole” for Malaysians who can’t do anything else due to low esteem and lack of opportunity.

This is where the TVET system must be revamped to make it accessible and flexible.

We must transform from a rent-seeking based economy to an innovation-led economy. And this should start within the informal sector.

The TVET system must play a major role in reframing “physical trades work” such as plumbing, electrical work, carpentry, tiling and masonry into a qualification through both formal instructions and apprenticeships to improve trade earning capacities.

There are shortages of good tradespeople across most urban areas in Malaysia.

There should be a return to craft-based manufacturing of shoes, tailoring, and household items that once existed generations ago.

There should be an emphasis on adding value to products within the informal sector.

Adding value to such products increases national productivity which is rapidly falling in Malaysia at present.

A lot can be learnt from the One Tambon One Product (OTOP) program that existed in Thailand a decade ago.

The same goes with food and beverages. Developing fusion food ideas increases value at pasar malam and stalls, while market gardeners can develop online home delivery systems. Such ideas can develop new value-added demand.

It is here where government development programs must be focused to make a difference. Innovation is a great tool to use in alleviating poverty.

For the rest within the informal sector, a minimum income safety net must be created to catch and support those who really need support.

This needs a “Robin Hood” taxation policy which taxes the super-rich and redistributes income to the B20.

The government must have the strength to undertake this. The money is already there, and such an initiative wouldn’t add anything to government debt levels.

If not, Malaysia will become a country with a small group of super-rich and a large group of citizens living in poverty.

This is not the Malaysia anyone should want.

Ignoring the informal sector will cost the country any chance of achieving uniform growth throughout the economy.

Without refocusing policy, the rich will get richer and the poor will become poorer, and Malaysia will continue to be stuck in the middle-income trap.

The best way to drive up wages within the wider economy is to raise incomes within the informal sector to put pressure on employers to offer better wages than what those within the informal sector can earn.

We must transform from a rent-seeking based economy to an innovation-led economy. And this should start within the informal sector.

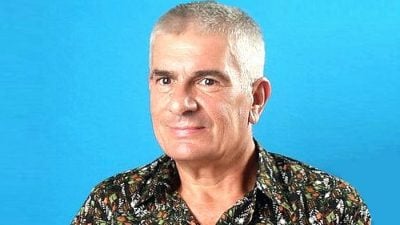

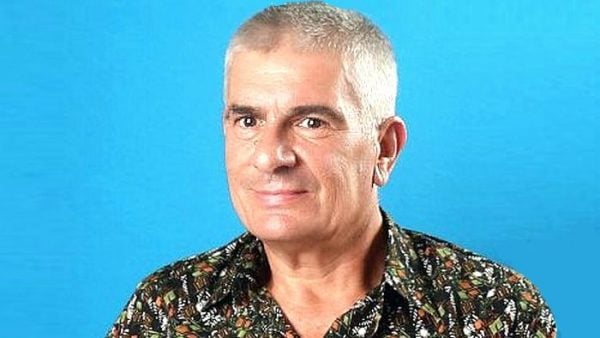

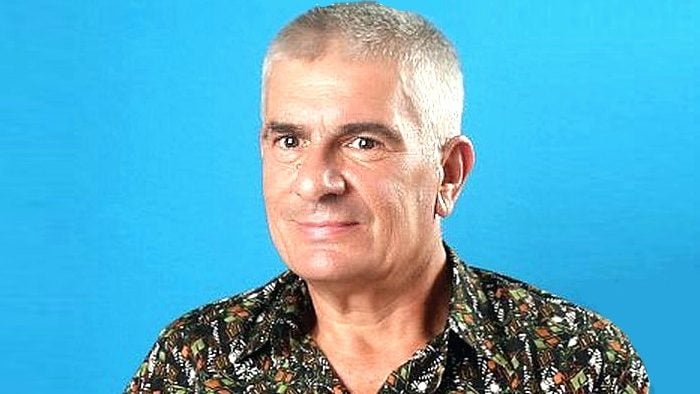

(Murray Hunter has been involved in Asia-Pacific business for the last 40 years as an entrepreneur, consultant, academic and researcher. He was an associate professor at Universiti Malaysia Perlis.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT