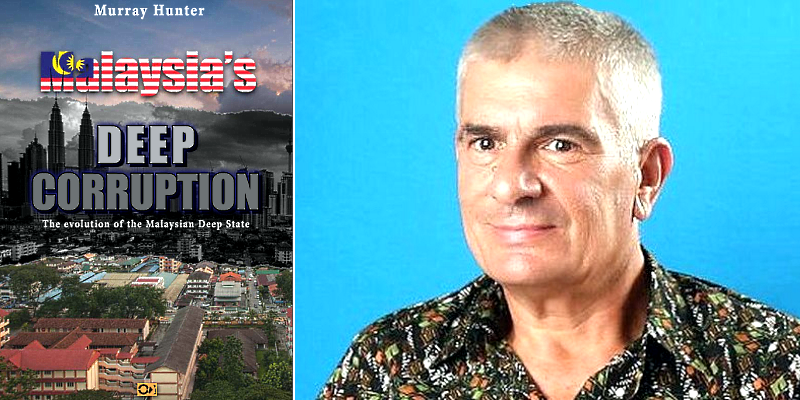

Murray Hunter’s latest work on this still sensitive subject, the evolution of the deep state, is presently available as a pdf volume for public viewing and dissemination (see Ovi Magazine and The Ovi eBooks).

Produced by OVI (door in English) a Finnish multilingual non-profit daily publication that carries articles related to human rights, inequality, discrimination and other contemporary hot button subjects, the collection appropriately opens the door to information, analysis and questions about the working and ramifications of a key shadowy player in the nation’s history and development.

The articles in the volume were initially intended as part of the two volume published set, Dark Forces Changing Malaysia, and Malaysia Towards GE15 and Beyond.

However discretion proved the better part of valor in deciding what to include and exclude.

The availability of these pieces on the internet hopefully will ensure the wide readership which the work thoroughly deserves.

For Murray’s work is not just about the massive monetary corruption associated with 1MDB and the mountain of financial scandals that have made the headlines and which the public is well acquainted with. It is about the larger and deadly cancer of debasement and degradation of the nation’s leading institutions — political, religious, economic and sociocultural — which has eaten away at the heart, soul and other parts of the nation’s body since independence, and has gone little checked.

The existence of the deep state in the country was first brought into prominence and public attention by Foreign Affairs Minister Saifuddin Abdullah in April and June 2019, when he accused deep state actors for the Pakatan government’s failure to ratify the Rome Statute and ICERD, the convention to eliminate racial discrimination.

According to him, “the deep state is real and it is out to sabotage Pakatan Harapan’s reforms and policies.”

Defined as a body of people, typically influential members of government agencies and the security authorities, involved in the secret manipulation or control of government policy, the deep state in Malaysia has been difficult to pinpoint because it consists of anonymous and amorphous individuals and groups that operate beneath, behind and sometimes namelessly in front of the political radar.

Other definitions of the deep state note its proclivity in allowing extremist mindsets and ideologies to flourish though its members may profess to hold outwardly moderate political positions.

It is almost certain that deep state elements — augmented and emboldened by social and political extremists — have been in play in the country for a long time.

Besides nameless bureaucrats and private entities, it has now grown to include participants from high levels of politics, economy and society who are in close communication and meet to strategize on ways — legal and extra-legal — to advance the “national’ agenda” — as well as their own interest.

This is done through a chain of command that begins with decisions of high-ranking officials and prominent personages which are then communicated to and implemented by lower rung supporters who may not be part of the original chain.

A critical catalyst in the development of the deep state is the nation’s civil service which has become a less inclusive and almost exclusively Malay enclave at the highest ranks.

Together the Malay-dominated bureaucracy and Umno and PAS, the two leading Malay parties, have redefined and reset the country’s politics and policies at both open de jure, and less obvious, de facto levels of power to ensure Malay dominance in society and the development of a fuller ethnocratic state.

But apparently dominance through justifiable and law-abiding measures and using legitimate and authorized agencies to advance their cause of an ethnocratic state are not enough for some extreme members of the deep state.

It has to be supplemented by malicious tactics, dirty tricks, unscrupulous behavior, intimidatory and illegal actions — some conducted in the open; others done secretly — targeting individuals, organizations, events or issues seen as threats or antagonistic to Malay dominance and the establishment of a fully grown ethnocratic state.

When deconstructing the deep state in Malaysia, it should not be assumed that the deep state is easily visible or identifiable, or is a single unified entity on any issue.

Despite lacking definitional clarity, the deep state in Malaysia can be likened to an extra legal hydra with multiple points of outreach and goals, and what may appear to be opposing leadership with outwardly divergent aims and different strategies, but which in reality stems from the same genus of “ketuanan Melayu” and increasingly now, “ketuanan Islam.”

Murray’s expose of the deep state begins with an analysis of the Special Branch.

His detailed description of how the SB works and its deep state operations is revealing and leads to his warning that if Malaysia aspires to be a true democracy, then the SB is out of control (p.17).

Just as riveting is his inclusion of the monarchy as among key players that have an impact on deep state activities.

With its special position in the nation’s constitutional system guaranteed, the monarchy can perhaps be the leaders in countering the activities of deep state players, not only those that may harbor anti-monarchical sentiments.

The growth and role of Islamic institutions in deep state activities is examined with details provided — some drawn from personal knowledge — as also the forces and culture driving the larger civil service which he describes in the following way:

The Malaysian civil service is not apolitical. The majority of bureaucrats have a Malay-centric world view. Any policy or decisions that run counter are stalled or blocked, overtly or sub rosa. Malaysia’s civil service is strongly Islamized, with an extremely strong culture that suppresses any deviation from accepted assumptions, beliefs, and values embedded with this Malay-centric worldview. When Pakatan Harapan took over the government, ministers found this an insurmountable barrier to implementing reforms (p.41).

In mapping out the deep state operates and the nexus between the different players, he makes the key point also noted by other scholars of the system of crony capitalism that continues to be rampant.

The major objective of the “so–called deep state” is to seek, secure, and exploit rent-seeking opportunities, engineered by the players within the “political-institutional environment.” These “engineered opportunities” are created through legal monopolies, favoring certain parties, while keeping procurement opaque. Parties within the system protect the players from facing investigation and prosecution, over any charges of abuse of power.

Evidence of this with names, dates and details on how some of Malaysia’s “robber barons” have operated with impunity are provided together with the argument that they can be considered to be the legacy of the nation’s leaders, in particular, Dr. Mahathir.

Subsequent chapters, How the Malay elite hijacked Malaysia and Permanent Ethnic Malay Polity, go back in time and space to examine the Malay institutions put in place to shape the country’s political and socioeconomic destiny and the outcomes to date.

As with the other chapters, specificities are provided in a straightforward, no holds barred rendition of key events, milestones, personalities and institutions engaged in the development and life of the deep state.

Murray’s work in this volume does not indicate what the future is for the deep state, how much deeper it can go with increasing Islamization and the consequences for the nation.

Perhaps this will be provided later. For now, he has put together an illuminating expose of a well entrenched deep state embedded in an ethnocentric state, a possible Islamic state, and of the deep corruption that binds them.

This work is required reading for those wanting to know how the nation has arrived at this failed state stage as well as all who are wanting a better Malaysia.

Readers interested to know his further thoughts on the subject can read them in his website: murrayhunter.substack.com.

(Lim Teck Ghee is a former senior official with the United Nations and World Bank.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT