DUISBURG: Duisburg once touted itself as Germany’s “China city” due to strong links to the Asian giant, but it is now desperately seeking an image makeover as geopolitical tensions upend bilateral ties.

Located in Germany’s rust belt and long in decline, Duisburg got a welcome boost in 2014 when President Xi Jinping promoted it as a key stop on China’s new “Silk Road” during a visit.

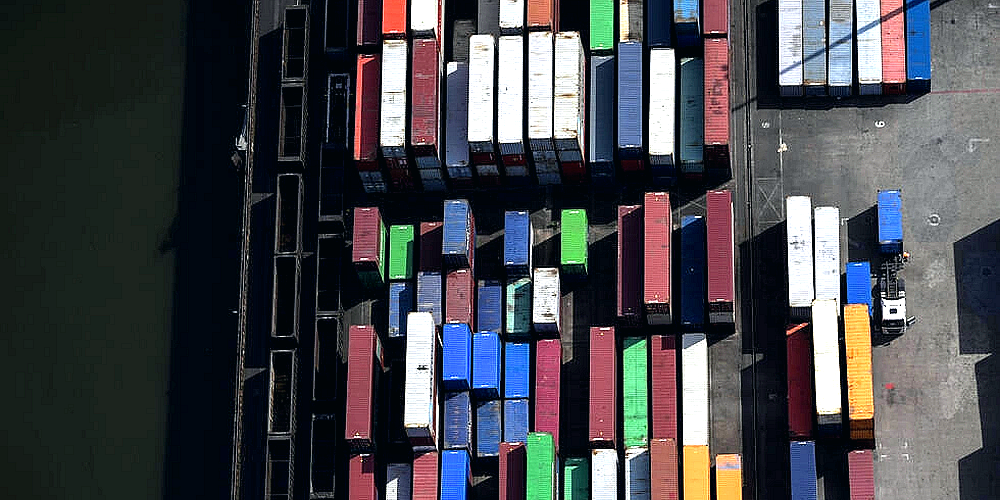

Huge numbers of freight trains were soon arriving from the world’s second-largest economy to the biggest inland port on Earth, and a flurry of China-linked initiatives followed.

But escalating tensions since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have prompted heightened concerns in Germany about relying too heavily on authoritarian powers, particularly China.

It comes as Europe’s top economy is taking a harder line against China, its biggest trading partner, on other issues ranging from Beijing’s saber-rattling towards Taiwan to its human rights record.

On the ground in Duisburg, population 500,000, the chill can be felt: a tie-up with Chinese telecoms giant Huawei has ended while shipping giant Cosco dumped its stake in a project at the port.

Markus Teuber, the dedicated China representative in Duisburg — the only German city to have such a role — insists that China remains an important partner but recognizes times are changing.

“There was a kind of ‘China hype’ after (President Xi Jinping’s) visit,” Teuber told AFP in an interview in the city’s town hall.

But he acknowledged that “the global political situation is different and it won’t change so quickly. It won’t be the same again as it was three, four years ago.”

Changing times

The shift in Duisburg, northwestern Germany, is a microcosm of what is happening in the wider economy as tensions rise between Beijing and Berlin.

Manufacturing powerhouse Germany has built up by far the biggest investments of any European country in China.

Just four of its companies — automakers Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes-Benz along with chemicals giant BASF — accounted for a third of European investment in China between 2018 and 2021, according to a study by independent research firm Rhodium Group.

But in the first quarter of this year, German exports to China plummeted 12 percent compared to the period a year earlier.

Big firms are being impacted, with Volkswagen and BASF both suffering first-quarter sales slumps in China.

“Europe and Germany are more siding with the United States, through the eyes of China they are seen more as allies to the United States,” ING economist Carsten Brzeski told AFP.

“Whether it is conscious or unconscious, there will be more reluctance to buy ‘made in Germany’ these days.”

This adds to other factors putting the economic relationship under pressure, such as Chinese firms now manufacturing products that rival those from Germany, he said.

‘Foreseeable risks’

Back in Duisburg, one of the most high-profile and controversial projects was the tie-up with Huawei, which has faced growing national security concerns in the West.

Officials and the company signed a memorandum of understanding in 2017 that aimed to transform Duisburg into a “smart city” but the agreement was allowed to expire at the end of last year.

Nothing concrete emerged from the tie-up, and it ended for “technical” rather than “political” reasons, Teuber insisted.

Another initiative that drew attention was Chinese shipping giant Cosco’s stake in a major new project in the port, Duisburg Gateway Terminal.

In June 2022, it transferred its shares to the port’s owner, although the Duisport group — which encompasses the owner and other companies — said the transaction “had no political background.”

Despite the worsening geopolitical climate, about 30 freight trains still ply the rail route between Duisburg and destinations throughout China each week, with the journey, at up to 15 days, quicker than sea shipments.

That is down from 60 to 70 trains a week during the pandemic, when port closures pushed up demand for rail freight, but around the same level as prior to it.

Officials now emphasize the approximately 200,000 containers traveling annually to and from China represent a small fraction of the four million handled by Duisburg’s port each year.

Duisburg is not about to close the door, however, with Teuber insisting that the city remains open to doing business with China, noting that Chinese delegations started visiting again in recent months after a pandemic hiatus.

Political opponents, however, remain convinced that focusing so heavily on China was misguided.

It was “definitely” a mistake, said Sven Benentreu, deputy chairman of the local chapter of the pro-business FDP party.

“The risks were already foreseeable several years ago.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT