HONG KONG: Two years after being released from a Hong Kong prison, Lau Ka-tung has lost count of the times he has returned — not as an inmate, but to offer support to pro-democracy activists in jail.

Hong Kongers like Lau, 27, are still grappling with the aftermath of huge, and often violent, protests that roiled the Chinese finance hub in 2019, and a subsequent crackdown by Beijing that saw thousands arrested.

Despite the collapse of organised opposition or pro-democracy activism due to a sweeping national security law passed in 2020, some Hong Kongers are still looking for ways to fight for their values.

During the protests, Lau, a registered social worker, had tried to mediate at a clash between police and demonstrators, an act that landed him in jail for six months for “obstructing police.”

“Everything felt incomprehensible and frightening… at the time I had an emotional breakdown, I was crying non-stop,” Lau said.

Now, he has made it his mission to ease those anxieties for jailed protesters and their families, making near-daily visits to prisons dotted around Hong Kong.

“Those who have spent a long time in custody are looking for emotional support, while those who just arrived often want to learn about the procedures and unspoken rules,” he said.

Frequently asked questions include how to write to judges to request leniency, and what types of supplies prisoners are allowed to receive.

Sometimes, prisoners just need someone to talk to, such as during one recent visit when Lau found himself engaged in a spirited chat about Chinese literature with a young pro-democracy protester.

Lau said there were very few social workers in Hong Kong specializing in protest-related cases.

“If I quit, the very small minority will become even smaller.”

‘Living through a crackdown’

Hong Kong’s protest movement kicked off in June 2019 over an unpopular bill that would have allowed extraditions from the semi-autonomous city to the Chinese mainland.

The movement soon morphed into a wider push for democratic change that brought hundreds of thousands of Hong Kongers from all walks of life onto the streets to take part in huge protests, some of which turned violent.

The subsequent crackdown saw more than 10,000 people arrested over the protests, with more than 6,000 still awaiting formal charges.

Under Beijing’s national security law, which sounded the death knell for the protest movement, another 150 people have been charged, with dozens of the city’s best-known democrats facing allegations of “subversion” and “foreign collusion.”

National security cases have, so far, had a 100 percent conviction rate.

The crackdowns have decimated Hong Kong’s once-vibrant civil society, which was made up of dozens of political parties and advocacy groups across a wide spectrum.

At least 60 groups — including the two largest pro-democracy labor unions and the organizer of a yearly Tiananmen vigil — have disbanded.

Still standing, however, is the political party League of Social Democrats, where 31-year-old Dickson Chau serves as external vice-chairperson.

“Civil society has been seriously atomized,” Chau told AFP.

The LSD was once known for its boisterous street-level campaigning, with activists using megaphones to deliver pro-democracy messages.

“The situation (now) is so bleak that we can only run into each other in courts or prisons and all we can have is small talk — no one would collaborate for any actions,” Chau said.

The group is now allowed only to operate a single booth at a designated location, and police scrutinize every word on their banners.

Police question every new volunteer, Chau said, and group members are warned not to protest around “politically sensitive” days, such as the anniversary of the city’s 1997 handover to Chinese rule.

Still, the LSD continues to oppose some government policies, such as a recent $74 billion project to develop new artificial islands around Hong Kong.

“Citizens can no longer speak out in public… but Hong Kong is not yet a pond of stagnant water,” Chau said.

Creating space

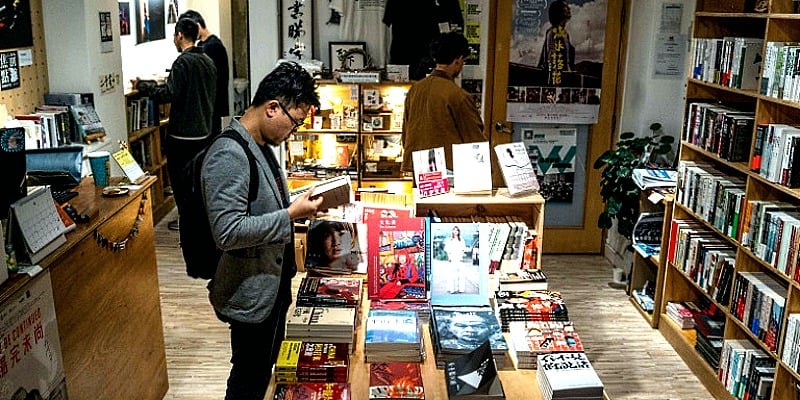

With the streets of Hong Kong cleared of rallies and protests, some have tried to build alternative spaces.

“Civil society around a decade ago was very different… Now, having a space is precious because we don’t have many groups and venues left,” said Sum Wan-wah, a veteran journalist who recently opened a bookshop named “Have A Nice Stay.”

Sum’s business partners are former reporters of Stand News, an independent online news platform that closed after police raided its newsroom and arrested its editors for “sedition.”

Since opening last May, the bookstore has registered over 1,500 members and organized more than 50 closed-door events — mostly talks by journalists, authors and documentary film-makers.

Many of the books on sale focus on media literacy, democratic development and authoritarianism. Events cover a range of topics, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to documentary production workshops.

The store also displays award-winning news photography and sells handicrafts made by reporters who have lost their jobs since the crackdown.

“As long as people can have a place to gather, there is no limit to what can be imagined,” Sum said.

“You won’t know whether it will make a difference or how many people it will nurture, but I want to give it a chance.”

The bookstore is not immune from pressure and surveillance, with the shop sometimes subject to inspections and event participants once questioned by police in the last year.

Sum remains undeterred.

“I don’t want a situation where nothing can happen,” he said.

“I am making a choice between zero and 0.1, and I choose 0.1 even though all the efforts may eventually go down the drain.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT