COPENHAGEN: Denmark inaugurates Wednesday a project to store carbon dioxide 1,800 meters beneath the North Sea, the first country in the world to bury CO2 imported from abroad.

The CO2 graveyard, where the carbon is injected to prevent further warming of the atmosphere, is on the site of an old oil field.

Led by British chemical giant Ineos and German oil company Wintershall Dea, the “Greensand” project is expected to store up to eight million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030.

In December, it received an operating permit to start its pilot phase.

Still in their infancy and costly, carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects aim to capture and then trap CO2 in order to mitigate global warming.

Around 30 projects are currently operational or under development in Europe.

But unlike other projects that store CO2 emissions from nearby industrial sites, Greensand distinguishes itself by bringing in the carbon from far away.

First captured at the source, the CO2 is then liquefied — in Belgium in Greensand’s case — then transported, currently by ship but potentially by pipelines, and stored in reservoirs such as geological cavities or depleted oil and gas fields.

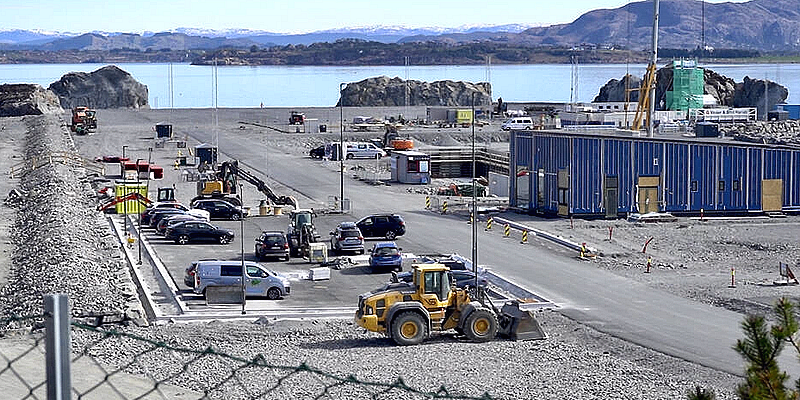

At Greensand, the carbon is transported in special containers to the Nini West platform, where it is injected into an existing reservoir 1.8 kilometers under the seabed.

Once the pilot phase is completed, the plan is to use the neighboring Siri field as well.

Danish authorities, who have set a target of reaching carbon neutrality as early as 2045, say this is “a much needed tool in our climate toolkit.”

“It will help us reach our climate goals, and since our subsoil contains a storage potential far larger than our own emissions, we are able to store carbon from other countries as well,” Climate Minister Lars Aagaard told AFP.

North Sea advantages

The North Sea is particularly suitable for this type of project as the region already has pipelines and potential storage sites after decades of oil and gas production.

“The depleted oil and gas fields have many advantages because they are well understood and there are already infrastructures which can most likely be reused,” said Morten Jeppesen, director of the Danish Offshore Technology Center at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

Near the Greensand site, France’s TotalEnergies is also exploring the possibility of burying CO2 with the aim of trapping five million tonnes per year by 2030.

In neighboring Norway, carbon capture and storage facilities are already in operation to offset domestic emissions but the country will also be receiving tonnes of liquefied CO2 in a few years’ time, transported from Europe by ship.

As Western Europe’s largest producer of oil, Norway also has the largest potential for CO2 storage on the continent, particularly in its depleted oil fields.

Room for improvement

While measured in millions of tonnes, the quantities stored still remain a small fraction of overall emissions.

According to the European Environment Agency (EEA), the member states of the EU emitted 3.7 billion tonnes of greenhouse gases in 2020 alone, a year that also saw reduced economic activity owing to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Long considered a complicated solution with marginal use, carbon capture has been embraced as necessary by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA).

But it remains far from a miracle cure for global warming.

The energy-intensive process to capture and store the CO2 itself emits the equivalent of 21 percent of the gas captured, according to the Australian think tank IEEFA.

And the technology is not without risks, according to the think tank, which says potential leaks could have severe consequences.

Furthermore, the cost of the project has not been made public.

“The cost of CO2 storage must be reduced further, so it will become a sustainable climate mitigation solution as the industry becomes more mature,” Jeppesen said.

The technology also faces opposition from environmentalists.

“It doesn’t fix the problem and prolongs the structures that are harmful,” Helene Hage, head of climate and environmental policy at Greenpeace Denmark, told AFP.

“The method is not changing our deadly habits. If Denmark really wants to reduce its emissions it should look into the sectors that are producing a lot of them,” she said, singling out sectors such as agriculture and transportation.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT