Malaysia’s food security issues continue to be a ticking time bomb as the food crisis that already has caused devastating inflationary pressure worldwide appears to be only brewing. Not even near full blown eruption.

With such a perspective on the horizon, prioritizing and fast-tracking setting up a stream-lined and cost-efficient, fully localized farm-to-table supply chain for critical food items for Malaysians to minimize wastage and improve availability and affordability while also reducing the negative environmental impact cannot be underscored enough.

According to the World Bank commodities price index, global fertilizer prices rose 80% during 2021, 53% throughout 2022 and are forecast to ease only by 5% in 2023 (“Commodity Markets Outlook” from October 2022). However, we probably did not feel the real impact of these price increases due to a lag of 1 to 1.5 years between producing fertilizers and putting food on our plates – the food we put on our table today was produced six months ago using fertilizers purchased one year ago.

In fact, that slight cooling off of the fertilizer prices appears to be because farmers worldwide are reducing the volume of fertilizer purchases while cutting agricultural produce against the backdrop of rising fertilizer prices.

There was a noticeable drop in global fertilizer demand from 203.8 million tons in 2019/2020 to 198.2 million tons in 2021/2022 compared to a prior steady historical year-on-year increase.

If persistent, this trend may lead to a significant decrease in the volume of the global harvest in 2023, which, multiplied by geopolitical global trade distortions, threatens to exacerbate problems with rising food prices worldwide.

Therefore taking a ground-breaking integrated systematic approach supported by technology to eliminate all the voids and inefficiencies in the national food supply chain (FSC) is an urgent action item for Malaysia.

The broader concept of being food-secure is nearly indistinguishable from the FSC efficiency and resilience. This is why initiatives to strengthen national FSC take the central stage in the Malaysian Food Security Framework, proposed earlier by EMIR Research (refer to “Reinventing Malaysian Food Security Framework” in two parts).

On the global landscape, the recent pandemic and geopolitical shock-waves also awakened the consciousness to support local communities and local farmers, with many nations adopting more self-prioritizing and self-reliant policies with a dramatic shift to local production and shortening of supply chains.

Therefore, EMIR Research would like to re-emphasize a few fundamental building blocks for having an efficient national farm-to-table supply chain that must be a matter of emergency to the new administration.

Short, fully localized, dispersed but well connected FSCs

One of the main reasons for food insecurity is that humanity has stopped producing food close to its consumption places. As a result, FSCs are extremely long, often stretching around the globe, and subject to substantial disruption risks (due to regional and global force majeure events) and transportation/storage costs that eventually build into consumer prices.

Completely localized FSCs for critical food items

Recent global shocks have powerfully emphasized that at times of crises, we cannot eat cash or drink palm oil even if its production is our “comparative advantage.”

Therefore, the production of critical food items based on nutritional value for human health while also considering the composition of staple food ingredients across the different ethnic groups comprising Malaysia’s population, including all the required inputs (such as feed, fertilizers, chemicals and even 4IR tools), must be localized and formally (through dedicated ministries and agencies) uplifted to the status of national security.

Also think about the amount of higher paying jobs it can create due to tech involvement!

Scale-up cooperatives

Smallholder farmers produce more than two-thirds of the world’s food.

Yet, despite their key role in the regional and local food system, they do not receive enough compensation for their produce as they are generally exploited by the layers of intermediaries (layers and layers of additional costs to an eventual consumer) after the farm gate in the value chain. This is why agricultural sector is still associated with much poverty.

But when shocks hit the value chain, the impact is mainly felt by farmers and consumers, not players in between them.

The cooperative business model is a powerful solution to build sustainable value chains for small farmers.

From the production side, cooperative enables collective purchase (therefore, at lower cost) of inputs, such as feed, fertilizers, chemicals, machines and other materials.

On the other side, farmers can collectively bring their produce directly to consumers bypassing the layers of middlemen and other aggregators.

In the Malaysian context, EMIR Research has already tried to attract the attention of policymakers to the extraordinary work of Pertubuhan Peladang Kawasan (PPK) Kuala Langat, for instance.

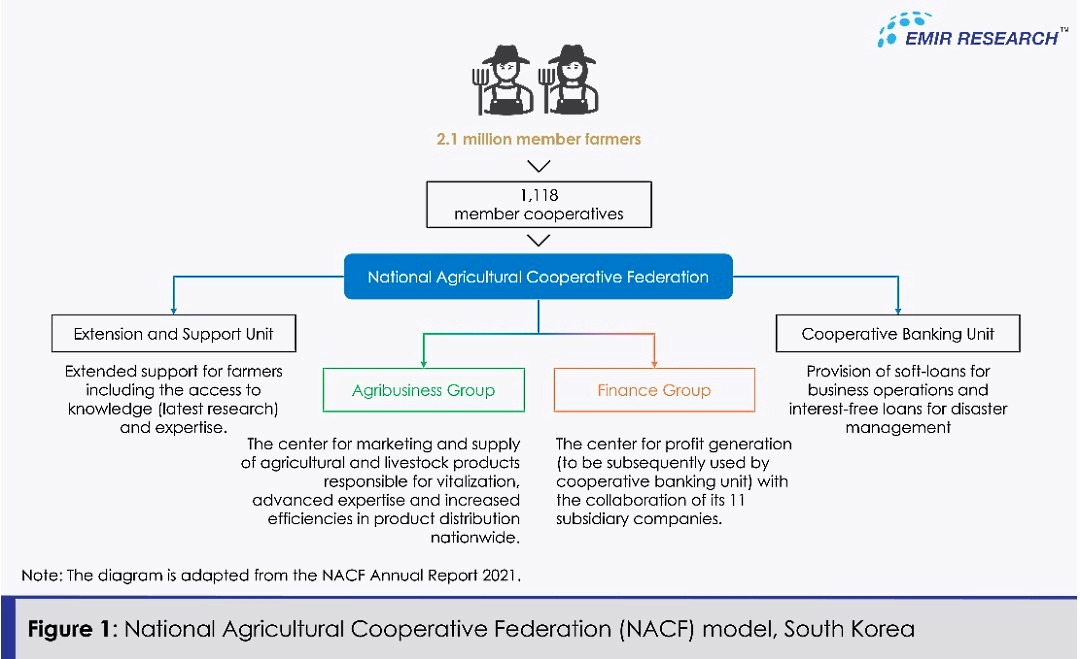

However, South Korean National Agricultural Cooperative Federation (NACF) model (Figure 1) is an excellent example of perfecting and extending the PPK model to a national scale success.

NACF, by extending its business to own retail and marketing arm (nationwide web of outlets) in the national value chain and being a kind of “one-stop solution centre” to all smallholder farmers’ needs, provides agile and resilient FSCs all geared solely to the benefits of farmers and consumers by disintermediating layers of usuary – middle-men, third-party delivery providers, financial and other exploitative aggregators.

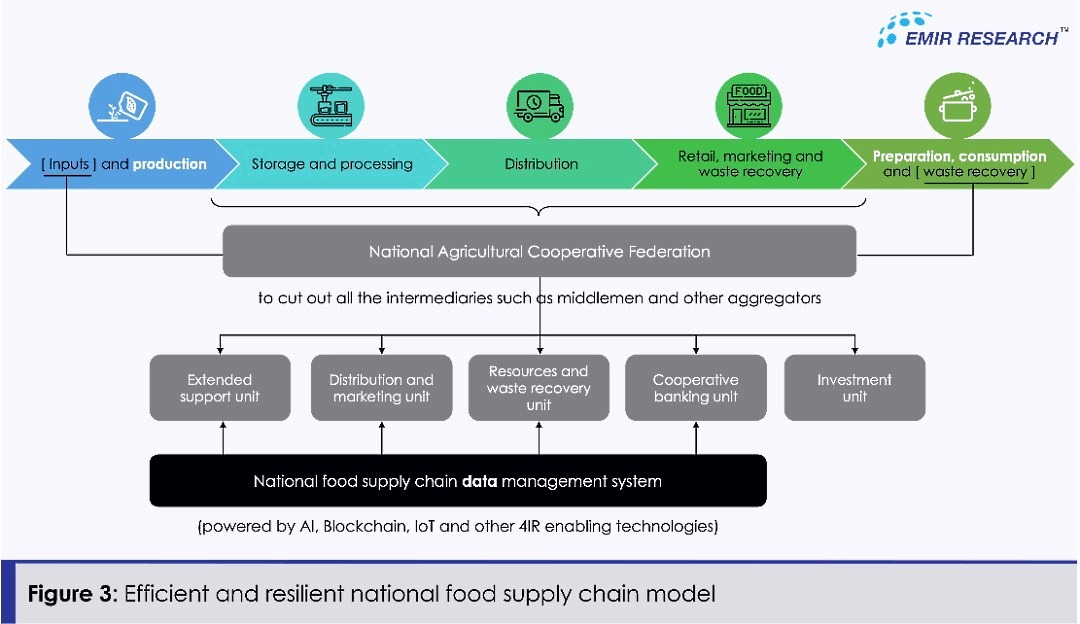

A single national FSC data-management platform can further strengthen such a web.

National FSC data-management system

EMIR Research has already emphasized that having such a platform, which, by the way, is already championed by other nations, opens the possibility for closer coordination of costs and prices, especially during crises, to ensure the survivability of industry players whilst minimizing price impact to end consumers.

Furthermore, generating and collecting more detailed and comprehensive information along the entire FSC allows us to algorithmically (through AI and other 4IR tech) optimize our ability to efficiently produce and distribute food nationwide, predict possible interruptions and rapidly act upon this knowledge.

For example, within such a platform, AI analytics can be naturally deployed to organize strategic and emergency food reserves to smooth consumption shocks over time, whereby, based on market intelligence, food can be strategically released in the market to prevent spikes in prices.

Scale-up urban farming

As most food consumption occurs within large urban centers, scaling-up urban farming can significantly relieve strain from the overall national FSC (for more practical considerations by EMIR Research, refer to “Turning Empty Spaces into Urban Farms”).

Therefore, while focusing on smallholder farmers in rural areas, NACF-like organisation can also focus on urban Agri-preneurs venturing into vertical and complete control environment farming. The unemployed youth should be particularly targeted by providing training under NACF’s extended support facility.

Digitalisation and automation

The focus on smallholder farmers is also important because the recent pandemic has highlighted how markets dominated by a few large players in the food industry are fragile.

And, in the 4IR reality, large players no longer preserve the advantage of scale.

With its cost quickly recouped, the 4IR-tech application by small farmers leads to the elimination of weather-related risk and increased yields and profitability (for proven concept in the Malaysian context, refer to “4IR enabled farmers: Solving national food security”).

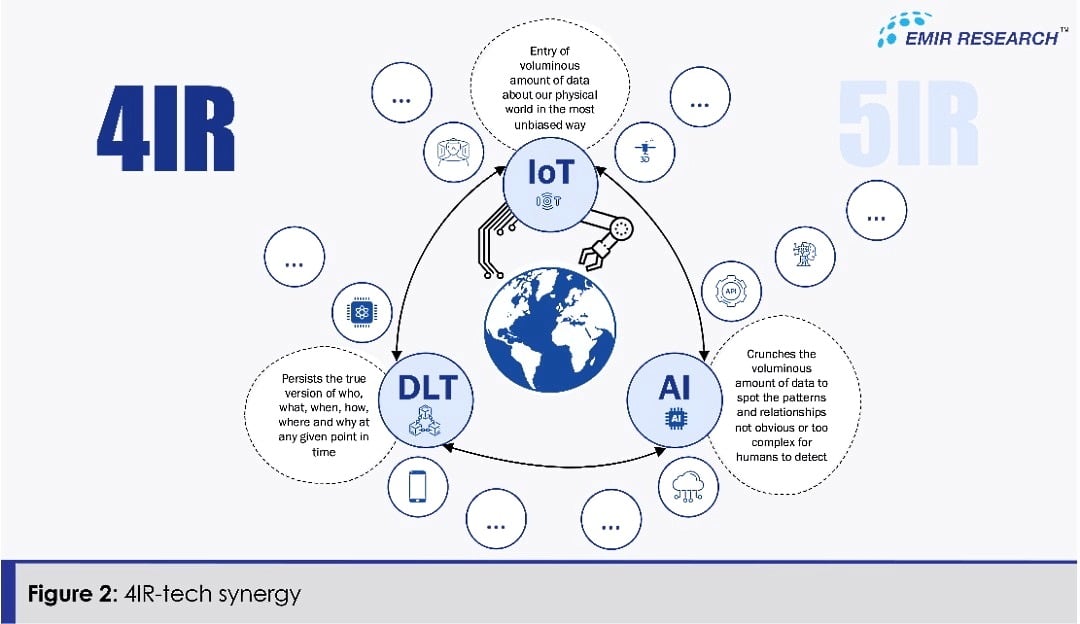

Furthermore, widespread digitalization and automation in Agri-sector will readily feed the national FSC data-management system with data more resilient to corruption and change when Internet of Things (IoT) is combined with the Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and AI (Figure 2).

Digitalisation and automation are also essential to our future pandemic preparedness and systematically tackling food loss and waste in FSC.

Robust infrastructure

EMIR Research already emphasized how the lack of basic transport infrastructure leaves many small farmers at the mercy of middlemen jeopardizing our food security and economic growth.

According to OECD estimates, a 10% improvement in transport and trade-related infrastructure quality can potentially increase developing countries’ agricultural exports by 30%.

However, as measured by “Supply chain infrastructure,” one of the indicators of the Global Food Security Index (GFSI), Malaysia has experienced the hardest drop, both in terms of score and rank, in 2022 within the Asia and Pacific region, among 23 countries.

This weakness is mainly due to Malaysia’s mediocre “road infrastructure” and deteriorating performance in terms of its “air, port and rail infrastructure” and “planning and logistics” – a score, based on the World Bank Logistic Performance index, which in turn uses six indicators related to main inputs to the supply chain performance outcomes.

Figure 3 summarizes all the above key elements by building on the NACF model.

Far-reaching implications for the nation

Besides developing global supply chains, developing a different national supply chain featuring a larger number of smaller localized FSCs, will be an alternative method to promote sustainable national economic development in general and small farmers in particular.

The empirical research of small farmers in developing countries demonstrates how sales method through short FSCs with good linkages among chain actors ensures the excellent quality of products and brings more benefits not only to farmers but also consumers: stable Agri-input and -output prices, increasing satisfaction and confidence of the farmers and more stable jobs in the rural areas.

For example, the survey conducted in Vietnam on short FSCs showed that each farmer also created 2.4 full-time jobs, 5.6 part-time jobs, or approximately 3.41 full-time equivalent jobs for rural people.

On top of that, the small farms were as likely to employ women as men, while big farms generally prefer hiring men.

It is logical to expect a similar (even greater) effect to be achieved through the support of urban farmers in areas where food consumption is denser and higher technologies and research can be involved.

Even though, in line with the global trend, in the short-term Malaysia must prioritize local market, connecting smallholder farmers into a web/network of supply chain will allow them also to participate in the global value chain bypassing intermediaries that often act as gatekeepers of the global value chain.

Needless to mention how, if these initiatives were implemented, the lives of Malaysia’s rural and urban unemployed and underemployed, including youth, would never be the same as they were during the endless decades of feudal subsidies and handouts.

Finally, the lives in our rural areas would probably be re-vitalized and even become a centre of attraction while relieving stress in urban areas, expanding industry, fostering economic growth and tackling our food security systematically.

(Dr. Rais Hussin is the President and Chief Executive Officer of EMIR Research, a think tank focused on strategic policy recommendations based on rigorous research.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT