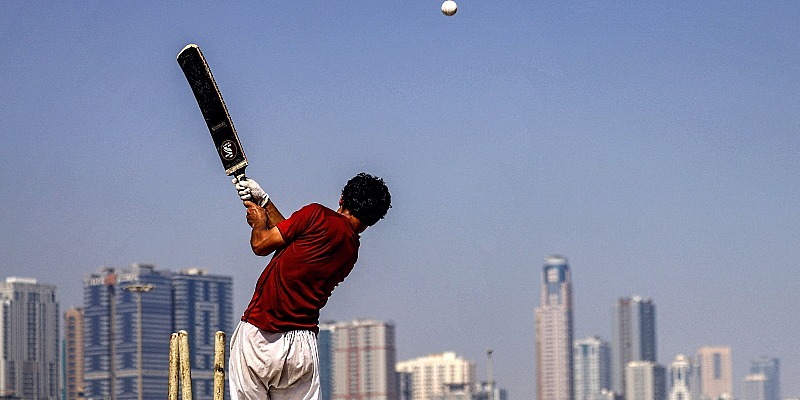

DUBAI: It is 7:00 am in Dubai and as the sun peeks above high-rises, it reveals an animated scene below: about 200 people, mostly men, wielding bats and taped-up tennis balls in a weekly festival of street cricket.

About a dozen informal games are in progress in a carpark near the city’s financial district, as metro trains glide across a bridge overhead and police watch from a parked SUV, wary of players bringing alcohol or otherwise misbehaving.

Every weekend, such games are played on spare patches of ground across the Gulf region, which is home to millions of migrant workers and expatriates from cricket-loving South Asia.

And even as the Gulf, namely Qatar, gears up to host the first football World Cup on Arab soil, another tournament dominated conversation among the players in Dubai: cricket’s Twenty20 World Cup, which was unfolding in Australia.

Faisal, a 35-year-old Pakistani who drives for a living, followed the tournament so avidly that he nearly crashed during India’s tense win over Pakistan in October.

“I was almost in an accident — I was watching my phone, the India-Pakistan game,” he said. “We really love cricket.”

There’s no question which is the prime sport among the Gulf’s migrant workers, whose treatment has been in the spotlight in the build-up to the Qatar World Cup.

Street cricket can often be seen in Dubai, much more commonly than football.

That’s a result of the huge numbers of South Asians in the region, including an estimated 3.5 million Indians in the United Arab Emirates.

Making up about a third of residents, they dwarf the native population of around one million.

“We keep watching scores while playing cricket,” said Indian expat Dinesh Balani, 49. “While working, while in the bathroom or anywhere, we follow cricket.”

‘Our own bosses’

As the November morning heats up, more players arrive, clutching paper cups of karak tea, a Gulf specialty, and bags of bats and plastic wickets as they spill out of cars.

A children’s game is in progress in one corner of the carpark, while in another, an all-women’s team undergo a coaching session.

Tennis balls wrapped in tape — to make them less bouncy, which better replicates leather cricket balls for bowling and batting — hurtle across the tarmac, bumping off kerbs and rolling under parked cars.

Balani, who works in real estate, said he has played street cricket in Dubai since 1995. He runs a team, the D-Boys, with 30 players on the roster.

He said for many workers, often with boring or stressful jobs, cricket is an important outlet.

“A lot of us are between white and blue-collar workers,” Balani said.

So they have to go through a lot of things in the week. They listen to a lot of things from bosses and managers,” he added.

“But this is the one place where we vent out. Nobody is there to boss us. We are our own bosses.”

Amreen Vadsaria, 22, who was raised in New Zealand and is playing with the women’s team, says India’s Virat Kohli is her favorite player. She cannot name any footballers.

“I grew up outside of India, and I never really had an interest in cricket. But I think (playing street cricket) has made me want to follow cricket more,” she said.

“And because it’s such a big thing in my country in India, I think it’s brought me closer to my culture.”

‘Family get-together’

The players and their games have an itinerant history, moving from place to place as Dubai’s breakneck development turns their makeshift cricket grounds into tower blocks and malls.

Meanwhile, the UAE has become a fixture in professional cricket, hosting Pakistan’s home games for a decade after a 2009 attack on Sri Lanka’s team in Lahore.

India’s glitzy IPL Twenty20 competition shifted to the UAE for two years during the Covid-19 pandemic, and the oil-rich country also hosted last year’s Twenty20 World Cup, along with several Asian Cups.

While the UAE’s South Asian population ensures a ready-made fan-base for big tournaments, weekly cricket also acts as a glue for the community, according to Balani.

“This is what we have done from the age of five. We started playing and never stopped since then,” he said.

“It is part and parcel of our life… we became friends in cricket and then our families became friends and then our kids became friends and so on and so forth,” Balani added.

“So this is not only cricket, this is also like a family get-together for us,” he said.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT