WASHINGTON: The recent dismissal of an American professor, whose students said he graded too harshly, has ignited debate in the United States about universities that bend too much to the wishes of their students.

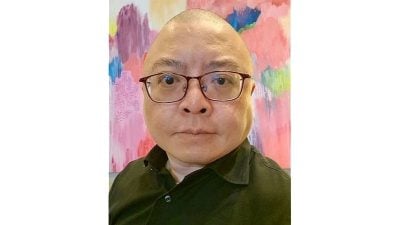

Maitland Jones, who taught organic chemistry at New York University (NYU), was dismissed in August without a prior interview or clear explanation, leaving him “baffled,” he told AFP.

Eighty-two of his students signed a petition to complain about his grading, which they considered too harsh.

“The students who wrote the petition were… not able to accept the fact that they were not doing well… They looked around for someone to blame,” Jones told AFP.

Jones estimated that only a quarter of his 350 students failed to achieve a passing grade.

Jones’ dismissal at age 84 might have gone unnoticed without an article in the New York Times in early October, which sparked a heated debate. Prior to serving as an adjunct professor at NYU, a private university, Jones held prestigious teaching posts at Princeton and Yale.

Many other professors have offered support to Jones, decrying what they see as the disproportionate weight of the opinion of students, some with sensitivities heightened by social tensions and Covid-related lockdowns.

‘Power has shifted’

Marty Ross, a professor emeritus at Northeastern University in Boston, believes that some private universities patronize students in a country where students are routinely asked for feedback about professors and courses.

These “clients,” he said, tend to feel hostility toward hard subjects or ones outside their major, such as organic chemistry, and “develop a ‘why do we need this course?’ attitude.”

“If (they are) struggling, they give the course poor ratings and may go so far as to formally lodge complaints,” he told AFP.

In contrast, the retired environmental scientist said he knows of incompetent professors who manage to fill their classes just by having a reputation for being “easy graders.”

In the end, Ross said, “the power has shifted from faculty to students, which is not the best way to run a college. It is as though patients suddenly are telling surgeons how to operate.”

The deferential relationship between students and professors seen elsewhere doesn’t really exist in US faculties, said Karin Fischer, a journalist and research associate at UC Berkeley’s Center for Studies in Higher Education.

“In the United States, there’s this notion that you’re supposed to challenge authority in the classroom. You’re supposed to ask questions to your professors. You’re not supposed to assume that everything is through the gospel of them,” she said. “Debating and having discussions and questioning is part of the critical thinking mindset of the American university.”

Souradeep Banerjee, a young instructor at Temple University who spent most of his studies in India, said he first became aware of the power of US students when he was assigned the task of grading papers.

The professor of a course with 300 students in it sat Banerjee and three other teaching assistants down and told them they had to go easier in grading “because Temple’s finances and how the university runs basically depends on the enrollment of the students, right?”

Sky-high tuition

This business relationship is paramount to some students and their parents, who demand a quality of education commensurate with the sacrifices they make to attend college.

In the United States, it is common for a college student to pay up to $60,000 a year in tuition, not including housing, transportation, or food expenses. Many students take out large loans to finance their college education.

“The fact that they’ve had to borrow heavily does put a lot of pressure on them to get good grades,” Fischer said. Students want to do well “so they’re not having to spend additional semesters in college.”

Before enrolling in classes, Temple University freshman Daniela James said she considers how professors grade and checks out comments at RateMyProfessors.com.

“It puts a lot of pressure on me because I can’t afford to waste my time. I’m paying so much,” said James, who juggles two odd jobs outside of class, one on campus and one at a major US fashion chain.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT