It is parade season again, the season of celebrating hard-won freedoms.

Celebrations usually start in Malaysia at the beginning of August with various programs and national competitions.

On August 31, we will celebrate Independence Day or National Day in the Malaysian context.

In conjunction with National Day on August 31, it is an excellent opportunity to look back and ponder how the journey has been and where we are heading.

This year, in line with the Keluarga Malaysia concept as aspired by Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob, the theme of the National Day and Malaysia Day 2022 celebrations is “Keluarga Malaysia Teguh Bersama” or in English, Malaysian Family Strong Together, under the framework of inclusiveness, togetherness and gratitude.

It can also be viewed through the Merdeka 360 portal, the information hub for the National Day and Malaysia Day celebrations.

As we learned from the history textbook in school, National Day commemorated the independence of the Federation of Malaya from British colonial rule on August 31, 1957. It means we are freed from colonialism.

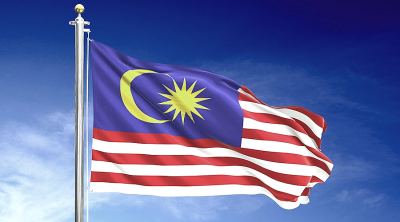

This month, we can see the flags everywhere in the city or the village. Have you ever wondered, “Why do we celebrate National Day? What is celebrated on National Day? What does it mean to be a Malaysian?”

National Day is a celebration of freedom. But how free are we?

We are not entirely free, as while we claim to celebrate the 65th anniversary of National Day every year, we are still debating whether we should focus on National Day or Malaysia Day.

Often confused with National Day, we also celebrate Malaysia Day which falls on September 16, 1963, when the former British colony of Singapore and the East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak joined the Federation of Malaya to create the Malaysian Federation.

Malaysia was formed only on September 16, 1963 following the merger of Sabah, Sarawak, Singapore and the Federation of Malaya. Singapore left Malaysia in 1965 and attained self-rule.

This was a historic event for Malaysia as it marked a new era. However, Malaysia Day was only deemed a public holiday in 2010. This gives a confusing picture of Malaysia’s creation.

More critical is the continuous debate on the version of history that we teach our people, deemed incomprehensive. For instance, we have not also given a fair share of the role of leftist leaders.

We are not entirely free. All eyes are on when Malaysia’s next general election will be called, and we still do not know the date.

Every time close to the deadline for the general election, we hear so much uncertainty and speculation, yet this issue has not been resolved.

Why do we have to guess the general election date, and why can’t we have a fixed date?

A fixed date is needed to have a fair system for healthy competition between the ruling government and the opposition.

We live in a country where the Constitution guarantees fundamental civil liberties, whereas the government does not.

The 2018 political change from the Barisan Nasional (BN) to Pakatan Harapan (PH) was short-lived before the change of government took place again in March 2020 under the Perikatan Nasional (PN) until the present day with a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the government under Prime Minister Ismail Sabri and the PH.

It shows the absence of state legitimacy and weak institutions that promise a check and balance system to be in place.

We are not entirely free, as peaceful protests are still not allowed fully. However, the protection of fundamental civil liberties of Malaysians is spelled out at length under the second part of the Federal Constitution, under the section of fundamental liberties.

Nevertheless, some of these freedoms are qualified by an overriding right of the government to decide otherwise, if it wishes, in the interests of national security or public order.

The executive power has, in practice, left few guarantees of individual liberties.

Despite the Peaceful Assembly Act 2012, peaceful protests are still not fully allowed. For instance, 30 individuals who participated in the “Turun Malaysia” protest outside Sogo shopping complex in Kuala Lumpur were called up.

Negotiations were attempted with the authorities to continue their march but were unsuccessful.

In the present context, we are told that protest is not our culture. However, the fact is that we have failed to recognize the importance of our history, where protests had a huge role in our independence journey, for instance the Malayan Union protests in 1946 as an essential turning point in the rise of nationalism.

Unknown to many, October 20, 1947 was another historic day in the people’s constitutional struggle for independence from British colonialism.

We are not entirely free, as race and religion continue to dominate politics.

Polarization over race, religion and reform has afflicted Malaysia for decades and powerfully shaped its electoral politics.

We seem to have not learned from our history.

Malaysia’s ethnic divisions date back to the struggle for independence from British colonialism. A pivotal moment came in 1946 when the British formed one administrative unit, the Malayan Union, for the ethnically diverse states that would later become part of Malaysia.

Due to its colonial and political history, Malaysia’s political culture has developed into one that uses racial and religious discourse to gain votes and political power.

What can be done to right these wrongs and make our country freer to embrace the real meaning of independence?

We live in a country where the Constitution guarantees fundamental civil liberties, whereas the government does not.

Merdeka Day is not about flying the flags; the actual test of patriotism is when the country is challenged.

(Khoo Ying Hooi is Universiti Malaya Senior Lecturer.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT