Joining or ratifying dubious trade deals is supposed to offer miraculous solutions to recent lacklustre economic progress. Such naive advocacy is misleading at best, and downright irresponsible, even reckless, at worst.

TPP ‘pivot to Asia’

US President Barack Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’ after his 2012 re-election sought to check China’s sustained economic growth and technological progress. Its economic centrepiece was the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

But the US International Trade Commission (ITC) doubted the Washington-based Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and other exaggerated claims of significant TPP economic benefits in mid-2016, well before US President Donald Trump’s election.

The ITC report found projected TPP growth gains to be paltry over the long-term. Its finding was in line with the earlier 2014 findings of the Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture.

Meanwhile, many US manufacturing jobs have been lost to corporations automating and relocating abroad. Worse, Trump’s rhetoric has greatly transformed US public discourse. Many Americans now blame globalisation, immigration, foreigners and, increasingly, China for the problems they face.

Trump U-turn

The TPP was believed to be dead and buried after Trump withdrew the US from it immediately after his inauguration in January 2017. After all, most aspirants in the November 2016 election – including Hillary Clinton, once a TPP cheerleader – had opposed it in the presidential campaign.

Trump National Economic Council director Gary Cohn has accused presidential confidantes of ‘dirty tactics’ to escalate the trade war with China.

Cohn acknowledged “he didn’t quit over the tariffs, per se, but rather because of the totally shady, ratfucking way Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross and economic adviser Peter Navarro went about convincing the president to implement them.”

Cohn, previously Goldman Sachs president, insisted it “was a terrible idea that would only hurt the US, and not extract the concessions from Beijing Trump wanted, or do anything to shrink the trade deficit.”

But US allies against China, the Japanese, Australian and Singapore governments have tried to keep the TPP alive. First, they mooted ‘TPP11’ – without the USA.

This was later rebranded the Comprehensive and Progressive TPP (CPTPP), with no new features to justify its ‘progressive’ pretensions. Following its earlier support for the TPP, the PIIE has been the principal cheerleader for the CPTPP in the West.

Although US President Joe Biden was loyal as Vice-President, he did not make any effort to revive Obama’s TPP initiative during his campaign, or since entering the White House. Apparently, re-joining the TPP is politically impossible in the US today.

Panning the Trump approach, Biden’s US Trade Representative has stressed, “Addressing the China challenge will require a comprehensive strategy and more systematic approach than the piecemeal approach of the recent past.” Now, instead of backing off from Trump’s belligerent approach, the US will go all out.

Favouring foreign investors

Rather than promote trade, the TPP prioritised transnational corporation (TNC)-friendly rules. The CPTPP did not even eliminate the most onerous TPP provisions demanded by US TNCs, but only suspended some, e.g., on intellectual property (IP). Suspension was favoured to induce a future US regime to re-join.

Onerous TPP provisions – e.g., for investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) – remain. This extrajudicial system supersedes national laws and judiciaries, with secret rulings by private tribunals not bound by precedent or subject to appeal.

Lawyers have been advising TNCs on how to sue host governments for resorting to extraordinary COVID-19 measures since 2020. Most countries can rarely afford to incur huge legal costs fighting powerful TNCs, even if they win.

The Trump administration cited vulnerability to onerous ISDS provisions to justify US withdrawal from the TPP. Now, citizens of smaller, weaker and poorer nations are being told to believe ISDS does not pose any real threat to them!

After ratifying the CPTPP, TNCs can sue governments for supposed loss of profits due to policy changes – even if in the national or public interest, e.g., to contain COVID-19 contagion, or ensure food security.

Thus, supposed CPTPP gains mainly come from expected additional foreign direct investment (FDI) due to enhanced investor benefits – not more trade. This implies more host economy concessions, and hence, less net benefits for them.

Who benefits?

Those who have seriously studied the CPTPP agree it offers even fewer benefits than the TPP. After all, the main TPP attraction was access to the US market, now no longer a CPTPP member. Thus, the CPTPP will mainly benefit Japanese TNC exports subject to lower tariffs.

Unsurprisingly, South Korea and Taiwan want to join so that their TNCs do not lose out. China too wants to join, but presumably also to ensure the CPTPP is not used against it. However, the closest US allies are expected to block China.

The Soviet Union sought to join NATO in the 1950s before convening the Warsaw Pact to counter it. Russian President Vladimir Putin also tried to join NATO years after Vaclav Havel ended the Warsaw Pact and Boris Yeltsin dissolved the Soviet Union in 1991.

Unlike Northeast Asian countries, Southeast Asian economies seek FDI. But when foreign investors are favoured, domestic investors may relocate abroad, e.g., to ‘tax havens’ within the CPTPP, often benefiting from special incentives for foreign investment, even if ‘roundtrip’.

Stay non-aligned

The ‘pivot to Asia’ has become more explicitly military. As the new Cold War unfolds, foreign policy considerations – rather than serious expectations of significant economic benefits from the CPTPP – have become more important.

Trade protectionism in the North has grown since the 2008 global financial crisis. More recently, the pandemic has disrupted supply chains. With the new Cold War, the US, Japan and others are demanding their TNCs ‘onshore’, i.e., stop investing in and outsourcing to China, also hurting transborder suppliers.

Hence, net gains from joining the CPTPP – or from ratifying it for those who signed up in 2018 – are dubious for most, especially with its paltry benefits. After all, trade liberalisation only benefits everyone when ‘winners’ compensate ‘losers’ – which neither the CPTPP nor its requirements do.

With big powers clashing in the new Cold War, developing countries should remain ‘non-aligned’ – albeit as appropriate for these new times. They should not take sides between the dominant West and its adversaries – led by China, the major trading partner, by far, for more and more countries.

Related IPS articles:

- Weaponising Free Trade Agreements

- TNCs Reviving TPP Frankenstein

- CPTPP Trade Liberalisation Charade Continues

- Rethinking Free Trade Agreements in Uncertain Times

- Japan-led Pacific Rim Countries Desperate to Embrace Trump

- Model Trade Deal Con

- Lessons from the Demise of the TPP

- Trump, Clinton, Obama and the TPP

This article was originally published on KSJomo.org.

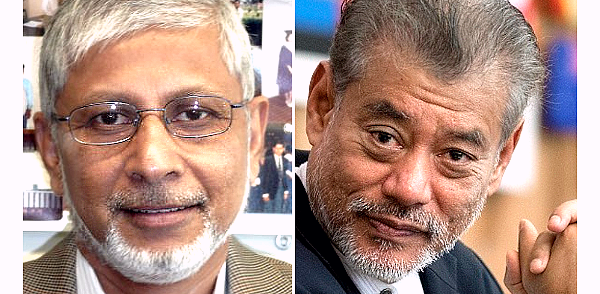

(Anis Chowdhury is Adjunct Professor, Western Sydney University and University of New South Wales, Australia. Jomo Kwame Sundaram was an economics professor and United Nations Assistant Secretary-General for Economic Development.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT