Before we celebrate and set our new year resolutions, let’s reflect on how the past two years have treated Malaysia’s economy.

2020 was a challenging year for countries worldwide. Since the COVID-19 pandemic’s outbreak, strategies, such as lockdowns and social distancing were implemented to prevent spreading the virus.

Although a World Health Organisation (WHO) study showed that lockdowns could suppress the COVID-19 pandemic, they have hurt the domestic economy.

The World Bank highlighted that the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic saw the number of people living on less than US$1.90 a day (extreme poverty) soar to 750 million people worldwide at the end of 2020.

In addition, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), the global unemployment rate increased by 1.1% to 6.47% in 2020.

Worldwide, policies such as interest rate reductions (monetary policy) and increased government spending (fiscal policy) were introduced to mitigate the pandemic’s economic impact.

Theoretically, lowering the interest rate increases borrowing, promoting consumption and investment. In comparison, increasing government spending increases aggregate demand.

Therefore, from a theoretical standpoint, such monetary and fiscal policies should stimulate production output, strengthen the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and increase economic growth.

Even though the stimulus response to COVID-19 has been the largest in peacetime, world output shrank by 4.3% in 2020, three times more than during the global financial crisis.

In addition, the ILO predicts that around 220 million people will be expected to remain unemployed globally in 2021.

Until now, Malaysia has introduced eight financial stimulus and comprehensive aid packages amounting to RM530 billion, with more than RM330 billion or 62% of the total allocation already utilised.

Although the Ministry of Finance has highlighted that the fiscal stimulus packages have benefited 20 million Malaysians and 2.4 million businesses as of Sept 24, 2021, the country’s economic recovery path remains subdued.

For instance, in 2020, Malaysia’s GDP contracted by 5.6%, while the unemployment rate rose to 4.5%, the highest since 1993.

Moreover, as of the third quarter of 2021, the country’s unemployment rate remained significant at 4.7%, with 746,200 unemployed.

Even more worrying, with the reimposition of strict containment measures in several states from July 2021, Malaysia’s economy contracted by 4.5% in the third quarter (the worst among ASEAN-5 countries: Indonesia 3.5%, Malaysia -4.5%, the Philippines 7.1%, Singapore 6.5%, and Thailand -0.3%, suggesting that even after the government has spent a whopping RM 330 billion to stimulate the economy, the path to economic recovery remains challenging and uncertain.

The global economic outlook remains precarious; global debt has risen to US$226 trillion (the most significant one-year debt surge since World War II).

Together with the evolving threat from the Omicron variant of COVID-19, are we being too optimistic to believe that the stimulus responses taken by Malaysia’s policymakers will revitalise the domestic economy? If not, what more can be done?

Although I am a proponent of increasing government spending to stimulate the local economy during hardship, policymakers should ensure that the execution of any stimulus responses is targeted, thoughtful and without leakages to generate the best outcomes from drafted policies.

For example, research shows that households which receive food baskets experience larger, positive impacts of food consumption and diet quality measures than those receiving cash transfers. Segambut MP Hannah Yeoh and Bangi MP Ong Kian Ming found that the nutritional content of food baskets distributed to vulnerable groups was overlooked.

This situation could have been avoided if nutritionists had been engaged to pick the food basket items.

Secondly, as highlighted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), policymakers should improve the quality of growth to ensure greater environmental protection and create conditions to develop a more innovative and dynamic economy, promoting higher living standards for all.

Thirdly, besides the grants, wage and hiring subsidies made available for micro, small and medium enterprises, policymakers could enhance job creation by encouraging commercial banks to increase loans to labour-intensive organisations.

Lastly, a survey conducted by the World Bank on more than 2,400 foreign investors in ten large middle-income countries highlighted that trade and investment policy uncertainty negatively affected their future investment decisions.

Thus, policymakers should promote political stability, strong institutions and good governance to stimulate investment sentiment in Malaysia.

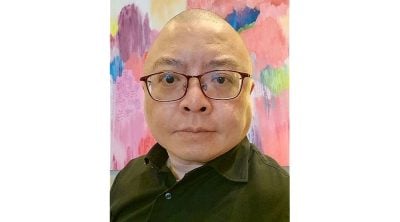

(Goh Lim Thye is Senior Lecturer, Department of Economics and Applied Statistics, Universiti Malaya.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT