By Qasim Nauman

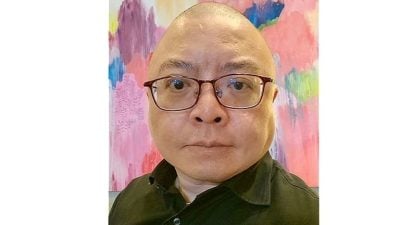

SEOUL, Sept 7 (AFP) – Afghan activist Omaid Sharifi’s art collective spent seven years transforming stretches of Kabul’s labyrinthine concrete blast walls with colourful murals — then the Taliban marched in.

Within weeks of the Islamists taking the capital, many of the street art pieces have been painted over, replaced by drab propaganda slogans as the Taliban reimpose their austere vision on Afghanistan.

The images of workers rolling white paint over the art were deeply foreboding for Sharifi, whose ArtLords collective has created more than 2,200 murals across the country since 2014.

“The image that comes to my mind is (the Taliban) putting a ‘kaffan’ over the city,” he told AFP in a phone interview from the UAE on Monday, referring to the white shroud used to cover bodies for Islamic burials.

But even as the Taliban erase the work of the ArtLords and despite being forced to flee for his safety, Sharifi said he would continue his campaign.

“We will never stay silent,” said the 34-year-old, speaking from a facility housing Afghan refugees.

“We will make sure the world hears us. We will make sure that the Taliban are shamed every single day.”

Among the erased murals was one showing US special envoy Zalmay Khalilzad and Taliban co-founder Abdul Ghani Baradar shaking hands after signing the 2020 deal to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan.

‘Everybody was running’

Sharifi co-founded ArtLords in 2014, using art to campaign for peace, social justice and accountability.

The prolific group often shamed the powerful in Afghanistan with street art, including warlords and allegedly corrupt government officials.

Their murals honoured Afghan heroes, called for dialogue instead of violence, and demanded rights for women.

ArtLords members braved death threats and were branded infidels by Islamist extremists.

They remained unrepentant, and kept at it until the end.

On the morning of August 15, with the Taliban at the gates of Kabul, Sharifi and five of his colleagues went to work on a mural outside a government building.

Within hours, they saw panicked people rushing out of government offices and decided to return to the ArtLords gallery.

“All roads were blocked,” Sharifi said.

“The army, the police were coming from all sides, abandoning their cars and everybody was running.”

When the group finally made it to the gallery, they learned that Kabul had fallen.

‘It never goes away’

Sharifi was 10 years old in 1996 when the Islamists first came to power, and he witnessed their harsh rule until US-led forces toppled them five years later.

This time around, he said, “I expect that not a lot has changed.”

Like Sharifi, many Afghans are sceptical of Taliban claims of a softer government.

Few have forgotten the public executions, and the blanket ban on entertainment — including on TVs and video cassette players.

Sharifi told AFP he “vividly remembers” the public punishments at a football stadium in Kabul, including beheadings and amputations for various crimes.

“When I was riding my bicycle to go to the central market… (I) would see a lot of broken TVs, broken cassette recorders and all these tapes,” he added.

“That is always in my mind. It never goes away.”

There was no local media to speak of during the Taliban’s first stint in power, and images of humans and animals were banned.

‘This is not the end’

Tens of thousands of Afghans rushed to Kabul airport as the capital fell, fearful of life under the Taliban, among them scores of artists and activists such as Sharifi.

“It’s a very difficult choice (to leave), and I just hope nobody ever experiences what we went through,” he said.

“Afghanistan is my home, it’s my identity… I cannot take out all my roots and plant myself in another part of the world.”

Sharifi’s primary concern was not violence, as he had lived with death threats for years.

“The scary part was that I will not have a voice,” he said.

“What really forced me was that I want my voice… I want my freedom of expression.”

The chaotic airlift from Kabul airport ended with the last US troops leaving by August 31, and Western governments admitted most Afghans identified as vulnerable to Taliban reprisals were left behind.

Sharifi said he was able to help 54 artists escape with their families, but more than 100 are still in the country.

“All of them are in hiding, all of them are fearful… They’re just trying to find a way to get out of Afghanistan.”

And he vowed to continue campaigning and creating art.

“I left (everything) behind,” Sharifi said.

“The only thing that keeps me going is that I think this is not the end.”

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT