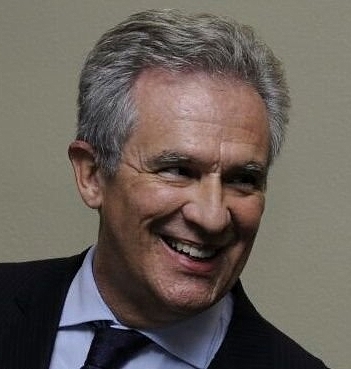

By Ary Norton de Murat Quintella

Like every big city, Kuala Lumpur requires time for one to get to know it well. Since I arrived, just over a year ago, the recurring waves of physical isolation caused by COVID-19 have limited my grasping of the city. Much of what I have learned about the capital was assimilated in the few weeks last year between late January and the beginning of the first Movement Control Order, in March.

For several weeks, I had wished to visit an independent bookstore I had heard about. Strictly speaking, I did not need another bookstore. The largest one in the capital is a ten-minute walk from where I live, across the KLCC park, which was designed by the Brazilian landscaper Roberto Burle Marx. I go there so often that I've become friends with one of its executives, Arthur, who is passionate about Brazilian music and knows about it much more than most people do, even in Brazil. On the date of Tom Jobim's birthday, in January, Arthur wrote to me to express his certainty that Brazilians "remember the maestro with fondness and gratitude". I've been told that one of the Malay Rulers has in Tom Jobim one of his favorite composers.

On the last Sunday of February, after watching the first season of an excellent Belgian crime series, I thought I needed to go out and recover from the murders I had seen on screen. Closing my laptop, I looked out the window. The day was cloudy; no sunshine, but no rain either. It was 4 p.m. I decided to call a Grab and go visit the independent bookstore.

Kuala Lumpur is today a symbol of modernity. In December, a Brazilian journalist known for his subtle sense of irony wrote to me, rather enviously: "It must be fascinating to celebrate the birth of Jesus in the set of Blade Runner". He couldn't have known it, but my wife's thesis was the very first in the world about Philip K. Dick, who was then a little-known author. As I got off the Grab, though, the urban landscape in front of me seemed not at all futuristic. I was standing opposite a four-story building from the 1950s, the Zhongshan. It didn't seem so very different from any small residential building in Copacabana or Ipanema from that same period.

The Zhongshan building houses small shops, all of them trendy, elegant and alternative. To define the spirit of the place, an American would say it is "hipster." A French person would say it is rather "bobo", meaning it has a bourgeois-bohême feel to it. On the ground floor, in an apothecary decorated in light-colored wood, all products sold are prepared without chemical components and come in brown glass jars. Next door, in a pale-toned decor, a shop sells notepads and leather notebooks near a charming-looking boulangerie and café that I later regretted not entering. The building also hosts an art gallery and fashion and decoration stores, but I couldn't check on them before closing time.

I started the climb to the bookstore, which is on the second floor. Halfway through, I saw a record store and walked in. The space was minimal and seductive. There were several Chinese old records for sale. The song that was playing while I lingered inside, however, was by a British roots reggae group called Black Roots. The album, In Session, had been released when I was a graduate student at the London School of Economics. However, I had never heard it. In my London days, I was always at university or in some museum or at the theater. There was then no space for roots reggae in my life.

Back on the stairs, I went up one more floor and got into the bookstore, which managed to be even smaller than the record store. I wondered if that was the smallest bookstore I had ever seen, or whether that distinction should go to Bahrisons in Khan Market, in New Delhi, which I visited in 2017 and felt so impressed with that I wrote about it at the time.

Well-organized and cozy, the place at the Zhongshan could be the welcoming library in a private home. I talked to Nazir, the bookseller. He told me that his name can be translated as "the one who brings the news", which I found premonitory. I asked what his criteria were for selecting the volumes, in view of the reduced space. "I choose to sell only the books I want to read," he said.

Nazir explained to me the name of his bookstore, Tintabudi. Until our conversation, I had not realized that in Malaysian tinta means exactly what the same word means in Portuguese – that is, ink. Just as tinta means ink in both languages, the word for cabinet, almari, reminds one of armário in Portuguese, and the word for church, gereja, sounds similar to the Portuguese igreja.

Budi, on the other hand, has a more metaphysical meaning. According to Nazir, it is a word derived from Sanskrit. It means something like "the spirit of goodness and rationality in human beings." A literal translation of the name of the bookstore could perhaps be: "The Texts Produced by the Ink of The Good Beings". That is beautifully appropriate for a bookstore.

Because of its small space, Tintabudi has to specialize. It focuses on the history of Asian countries, poetry, philosophy, contemporary themes. It carries recent and old books, new and second-hand. Two Brazilian fiction writers were represented, Jorge Amado and Clarice Lispector.

I bought three volumes. Keeping an Eye Open, Julian Barnes' essays on art collected in 2020, I had been coveting for several weeks. Joan Didion's Let Me Tell You What I Mean, published this year, brings together older texts which are surgical and concise. It is downright cruel how, without using a single mean word — Didion limits herself to simply showing and describing — an essay from 1968, "Pretty Nancy", annihilates Nancy Reagan, whose husband was at the time the governor of California. In another essay, "Why I Write", she says: "I write entirely to find out what I'm thinking". The description, in "A Trip to Xanadu", of a visit to William Randolph Hearst's castle in San Simeon concludes with the sentence: "Make a place available to the eyes, and in certain ways it is no longer available to the imagination". The third book, Horace and Me, I thought would make a good gift for a Latinist friend. Later at home, however, on perusing it after feeding Kiki, the golden Persian cat, I changed my mind. The tone of its author, the English journalist Harry Eyres, is so amusing when he speaks of his devotion, since school, to the poet Horace — and the school was Eton — that I decided to keep it. A chapter begins with the sentence, "I did not always get on with Horace."

The following day, at work, I boasted to my Brazilian collaborators about this trendy place, with its stylish and innovative stores, which I thought I had discovered. In a paternal manner, I recommended that they go visit the Zhongshan building. From one of them, who is very young, I heard, "I go there often. They usually have rock parties up on the rooftop". As lapidary as Joan Didion.

(Ary Norton de Murat Quintella is the Ambassador of Brazil to Malaysia. The author's Letters from Malaysia are published in the Brazilian newspaper Estado de São Paulo's philosophy and literature magazine, Estado da Arte. This article is a reduced translation from the Portuguese of Letter VII, published on March 6.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT