Like Malaysia, Myanmar used to be a British colony and the streets of Yangon are teeming with colonial buildings as well as old Chinese shophouses in the city's Chinatown.

The major thoroughfare in Yangon's Chinatown is Maha Bandula, known by the local Chinese as Guangdong Avenue due to the large number of early Cantonese migrants here.

It is difficult to distinguish between Chinese and the Burmese people today because they wear almost the same and practice almost the same lifestyle. The Chinese residents speak only Myanmar language and not Chinese.

The condition here nevertheless cannot speak for all Chinese in Myanmar. In northern part of the country, for instance, due to the geographical proximity to Mainland China, the Chinese residents there are very much influenced by China and where people from both countries have been maintaining very close relationship since very long ago.

The more recent influx of Chinese migrants took place during the colonial rule in the 19th century when most of the Chinese migrants arrived from sea, some landing in Malaya and Thailand while others landed and later settled down here in Myanmar.

The Chinese population in Myanmar is said to be around 3% of the national total, but actual percentage could be higher. In Myanmar's second largest city Mandalay, Chinese make up almost 30-40% of the city's population.

The Chinese people in Myanmar are mostly Hokkiens, Cantonese, Yunnanese and Hakkas. There ar many clanhouses here, such as the Hokkien Association of Myanmar which has a total of 49 subsidiary associations.

Myanmar Thye Guan Ong Clan Association is one of the many clanhouses in Yangon's Chinatown. During the anti-Chinese riots in 1967, all the furniture and fittings as well as the safe cabinet and stone tablets inside the clanhouse were destroyed. It took the owners four years to restore the building.

The Ong clan association was founded 110 years ago with the objective of promoting closer ties and solidarity among fellow clansmen, not unlike the many clanhouses in Malaysia.

Besides, gatherings are held here every Sunday morning. Aye Htun, the association's secretary told us, "Anyone can come in here and chat. Any problem can be voiced up and we will try to help."

Many local Chinese are reluctant to talk about the racial riots in 1967, when many shophouses owned by the Chinese were ravaged and destroyed. In addition, many innocent Chinese people were also killed.

Life did not get any better after the whole thing came to a rest. In 1982, the government enacted the citizenship law and identity cards were divided into red, blue and green cards, further limiting the rights of the local Chinese. Many local Chinese could only get blue or green cards, and they did not enjoy the same privileges as red card holders, including admission to certain popular university courses such as medicine and engineering.

Nationalization of Chinese schools

Besides, Chinese language education was also oppressed. In 1965. the government enacted the private school nationalization law that served to nationalize all private elementary and high schools in the country. As a result, more than 300 local Chinese schools were taken over by the government and the medium of instruction was shifted from Chinese to Burmese. Chinese language education was disrupted for over two decades, resulting in many Chinese people unable to read Chinese and many did not even know their family names.

In the second half of the 1980s, the government loosened its control of Chinese language education, allowing Chinese tuition classes to be set up.

Inside the Kheng Hock Keong temple not too far from the Ong clan association, Kheng Hock Keong Chinese language school was among the earliest Chinese tuition schools established in the form of a temple in Yangon. Despite the inadequate facilities there, the students nevertheless have the opportunity to learn the proper Chinese language and are much more fortunate than people a generation older.

Many of the Chinese people in Myanmar are now in their third or even fourth generations. The younger generation here were born when Aung San Suu Kyi was still under house arrest. Today, she is the State Counselor of Myanmar.

27-year-old Thin Thin Htay is a third generation Chinese living in Yangon. She speaks excellent Mandarin as well as the Yunnanese dialect. Growing up in Taunggyi, the capital of Shan State, she was surrounded by people who spoke Mandarin until her relocation to Yangon after high school.

Myanmar used to be a country with very limited information circulation, but today, Thin Thin Htay can connect with the outside world anytime through Facebook Google or Instagram. To her, free access to information can be both good and bad. The good thing is, people can have access to a whole world of information but the downside is that people will tend to criticize others mercilessly due to the convenience.

She said young Myanmar people are actually quite concerned about politics, and she herself is a big fan of Aung San Suu Kyi. Even though Suu Kyi has come under tremendous international criticism for the government's handling of the Rohingya issue, to her there is hope in the country so long as she is still in charge.

Young people her age are eager to travel abroad and see the outside world. Thin Thin Htay herself has been studying in Guangzhou for four years.

When asked whether she had plans to migrate, she said she did not have such plans yet.

"I always feel that life is more comfortable in my own country."

Once booming Chinese journalism

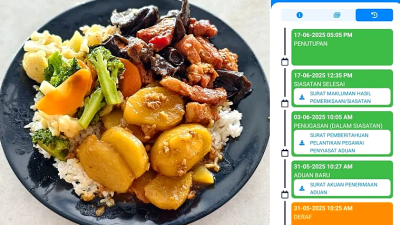

Myanmar Golden Phoenix is currently the only Chinese language newspaper approved by the government. Notably, the graphic artists there are all Burmese who don't read Chinese at all but are somehow able to lay out the pages quite nicely.

Myanmar used to experience a boom in Chinese journalism some four decades ago. According to Golden Phoenix CEO Htoo Aung, there were almost a dozen Chinese language newspapers in Yangon during the heyday, but due to political reasons later, all Chinese language media were either nationalized or shut down. For the subsequent almost 30 years, there were no Chinese language newspapers in the country, and although there was one Chinese language newspaper founded later on, it ceased operation after only a few years due to one reason or another.

Golden Phoenix was launched in 2007 as a monthly magazine initially before it was changed to fortnightly and now weekly.

Htoo Aung said before the restrictions on media were lifted in 2012, all newspapers in the country had to be sent for government vetting before publication.

The liberalization also saw the emergence of a multitude of publications. According to Htoo Aung, the number of newspapers and periodicals in Myanmar surged from 11 prior to 2012 to over 500 during the peak in just two years.

However, due to stiff competition, the total number of print and online media today has been drastically reduced to just about 200.

Before the liberalization, certain issues were completely banned from the media.

"The most obvious thing was Aung San Suu Kyi, who must not appear in the publications. One particular publication was suspended for several months for carrying reports on her."

International bias

Rohingya issue has become an international focus in recent years.

Htoo Aung feels that it is unfair and unreasonable for the international community to hit out at the Myanmar government over the Rohingya issue because they do not understand the nature of the problems in Rakhine State.

"I personally have been to Rakhine State and from what I observe, the situation there is not like what the Western media have reported.

"We have also carried reports on the place but as soon as the reports were published, we came under tremendous criticism because they thought we were undemocratic but the people here don't actually think this way."

Despite the stagnant economy under the NLD government, Htoo Aung said no media would sing the opposite tune in Myanmar. "Aung San Suu Kyi is the spiritual symbol of this country and currently there is no one else who can take her place."

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT