As reported cases of rape involving students are on the rise and the same for sexual abuse cases involving teachers, one can’t help but worry about the safety of their children at school.

In an exclusive interview with Sin Chew Daily, SAC Siti Kamsiah Hassan, principal assistant director of Bukit Aman’s Sexual, Women and Children’s Investigation Division (D11), revealed that reports of child sexual abuse and molestation are rising steadily.

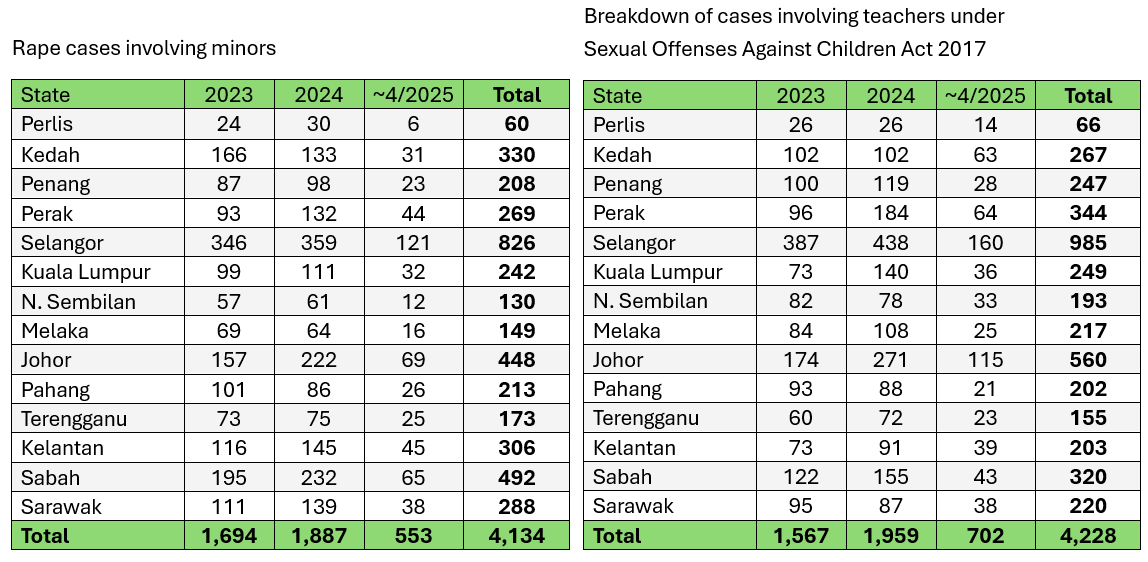

Between January 2023 and April 2025, police received 4,134 reports of rape involving minors, translating to an average of about five underage victims per day.

SAC Siti Kamsiah Hassan noted that Selangor recorded the highest number of such reports over the past 28 months with 826 cases, followed by Sabah (492) and Johor (448).

Cases involving teachers have also increased too, with a total of 4,228 reports of child sexual abuse received between 2023 and April 2025—1,567 cases in 2023 and 1,959 last year, and 702 cases for the first four months this year.

Selangor topped the list with 985 cases, followed by Johor (560 cases) and Perak (344 cases).

These statistics on campus-based sexual crimes involving minors and teachers reflect a grim reality: students are increasingly at risk of encountering “demons” in schools.

Many more victims are unable to send out distress signals—or don’t even know how to.

The institutions they trust most, environments widely regarded as safest, have instead inflicted the deepest wounds on them and their families.

According to experts, minors are prime targets for predators because offenders believe victims will feel too ashamed or embarrassed to speak out—allowing perpetrators to escape justice.

Following a string of bullying incidents and student suicides, society was further shaken by the horrifying case of a 15-year-old girl in Melaka sexually assaulted by a senior student on campus, and another gang rape involving students in Kedah.

One explosive incident after another has left parents and the public reeling in shock and fear.

The alleged campus sexual assaults in Kedah and Melaka are especially chilling because in these cases, groups of students not only committed the assaults but also filmed the acts.

School walls failed to protect them.

Beyond these reported cases lie even more hidden, invisible demons—individuals who should have been guardians of students but have instead exploited their positions and trust to prey on children.

High walls built from fear, the passage of time, emotional manipulation, public pressure, destruction of evidence, and legal complexities have allowed many predators to roam free for years.

Even as legal safeguards strengthen, these invisible barriers often prevent child victims from speaking up and render the truth nearly impossible to uncover.

In the case of the 15-year-old girl in Melaka, she was overwhelmed by fear and anxiety that she refused to return to school.

Had it not been for a teacher who discovered an indecent video circulating in a student group chat and alerted the girl’s mother, this case might have vanished without a trace, leaving the victim to carry her trauma alone for life.

Investigating child sexual abuse cases presents police with six particularly difficult—and heartbreaking—challenges.

During the interview, SAC Siti Kamsiah Hassan emphasized that overcoming these obstacles require close collaboration between investigators and psychological experts at every stage—from breaking through the victim’s emotional defense to preserving crucial evidence—if perpetrators are to be brought to justice.

1. Victims are afraid to report

Siti Kamsiah explained that young victims often don’t fully understand what happened to them; they only sense something was wrong.

Others stay silent out of fear—fear of being blamed, ridiculed by peers, or threatened by the abuser. Many choose to suffer in silence rather than reveal the truth.

“Many children don’t even know what ‘reporting to police’ means. Some fear that if they do, they’ll have to go to the police station and repeat shameful details in front of strangers,” she said.

She added that the unfamiliarity of courtrooms and legal procedures terrifies them.

Even with adult encouragement, many children refuse to cooperate with investigations.

2. Delayed reporting leads to incomplete evidence

Time is a major obstacle. Many victims only find the courage to come forward years later—sometimes as adults.

“We’ve had cases where victims reported assaults only after 15 years they occurred. By then, physical evidence is long gone—clothing discarded, perpetrators transferred or retired, crime scenes irreproducible.

“All police are left with is the victim’s testimony, which may be fragmented or hazy after such a long time,” she said.

3. Young victims struggle to reveal abuse

Even when incidents are reported soon after they occur, investigators face another hurdle: young children often lack the language to describe what happened.

SAC Siti Kamsiah noted that during interviews, officers must avoid leading questions—otherwise, defense lawyers may later challenge the admissibility of the child’s statement in court.

“You can’t directly ask a child, ‘Where did he touch you?’ The child might just vaguely say ‘here.’ That’s why every child interview must be conducted with a psychologist present. Officers must tread extremely carefully—making the process lengthy, complex, and highly demanding of professional skill,’’ she said.

4. Victims develop emotional attachments to abusers

More complex still are cases involving teachers.

Some victims, subjected to prolonged emotional grooming, develop feelings of dependency or even affection toward their abusers.

“Some teachers spend months or even years manipulating students into emotional dependence, making them believe they’re in a romantic relationship—even fantasizing about marrying their teacher after graduation,” she said.

These victims often protect their abusers during investigations—recanting statements, withholding information, or refusing to testify.

Adolescents aged 13 to 17 are especially vulnerable to such manipulation. Though victims, they end up fiercely defending their perpetrators.

5. Digital evidence is easily deleted

“Today, people hide their secrets in smartphones—but phones are also the most fragile evidence lockers,” SAC Siti Kamsiah said.

Once predators sense trouble, they quickly delete messages, clear chats, switch devices, or remotely deactivate accounts. Worse, some encrypted messaging apps permanently erase data that cannot be recovered.

Requesting data from overseas servers is time-consuming and bureaucratically cumbersome.

6. Public outcry silences victims

Media and social media attention can become another invisible shackle.

“While public exposure on social media may draw short-term attention and pressure authorities to act, it also thrusts victims into the spotlight.”

SAC Siti Kamsiah explained that victims are often labeled and gossiped about, and their families bear immense social stigma.

“Many parents, seeing online backlash, choose to settle quietly—hoping to spare their child from becoming neighborhood gossip.

“But if a case becomes too publicized without solid evidence, the predator may simply relocate. Without a conviction, he remains free—and a new victim may appear at his next destination,” she said.

SAC Siti Kamsiah stressed that overcoming these investigative challenges cannot rely on laws or systems alone.

It requires safer, more supportive environments for whistleblowing, access to professional psychological counseling, understanding from parents and institutions, and—critically—a public that refrains from unnecessary speculation, online vigilantism, and trial by social media.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT