It was a matter of time before another internal strife in Bersatu emerged into the open. And it has happened.

On Oct 14, Bersatu sacked five leaders, including Tasek Gelugor MP Wan Saiful Wan Jan, for violating the party’s code of conduct.

Machang MP Wan Ahmad Fayhsal Wan Ahmad Kamal, meanwhile, had his membership suspended for one term.

The other four who were sacked are all division chiefs: Mohd Azrudin Mhd Idris (Hang Tuah Jaya), Mohd Faizal Asmar (Pengerang), Mohd Fadhli Ismail (Ipoh Timur) and Mohd Isa Mohd Saidi (Ampang).

Bersatu’s disciplinary board said any of them may file an appeal within 14 days.

The moment Wan Saiful resurrected the 2019 sex scandal involving Azmin Ali last month, it became clear to many that Bersatu was entering yet another phase of internal turbulence. Azmin is the party’s secretary-general.

Such a move was not random—it was politically calculated and symbolically explosive.

By dredging up a scandal long buried, Wan Saiful sent a coded message: factions within Bersatu were ready to use any means necessary, including personal attacks, to weaken rivals and shift internal loyalties.

It reflected growing frustration among the rank and file, especially those sidelined after the party’s declining influence and confused post-election strategies.

Indeed, what followed only confirmed the suspicions. Bersatu’s leaders began turning on each other—subtle jabs became open attacks, and party unity quickly eroded.

The re-emergence of the Azmin scandal which allegedly took place in a Sandakan hotel in 2019 was not just an attack on one man but a spark that ignited deep-seated resentments over leadership direction, electoral performance, and ideological confusion.

In short, Wan Saiful’s statement didn’t just revive an old controversy; it exposed Bersatu’s fragile cohesion and the power struggles brewing beneath its carefully constructed image of solidarity.

After he was fired on Tuesday, a defiant Wan Saiful declared that “Bersatu does not belong to only one individual but to all members.”

The renegade MP was not simply expressing a democratic ideal—he was firing a parting shot at Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin and the party’s inner circle.

His statement was a clear insinuation that Bersatu had become overly dominated by Muhyiddin’s personal control, where dissenting voices were no longer tolerated.

By positioning himself as a defender of party democracy, Wan Saiful sought to frame his sacking not as an act of justified discipline but as political persecution for challenging the president’s authority.

In the larger context, his words carried a deeper subtext; that Muhyiddin’s leadership had lost its legitimacy among segments of the party’s grassroots and leadership.

Wan Saiful’s remark implied that Bersatu was no longer functioning as a collective movement but as a vehicle for one man’s ambitions and survival.

His defiance can thus be seen as an attempt to rally disillusioned members—especially those sympathetic to Azmin Ali or frustrated with the party’s diminishing relevance—to stand against Muhyiddin’s dominance.

In essence, Wan Saiful was warning that Bersatu’s internal revolt had only just begun.

The current power struggle within Bersatu underscores how far the party has drifted from its original purpose—and how deeply it is now mired in its own contradictions.

Formed by Umno dissidents who claimed to reject corruption and authoritarianism, Bersatu initially carried the moral banner of reform and Malay dignity.

However, that credibility began to crumble after the 2020 Sheraton Move—the very act that toppled the Pakatan Harapan elected government and earned Muhyiddin and Azmin the label of political traitors in the eyes of many Malaysians.

The duo was considered the prime movers behind the Sheraton treachery.

From that moment, Bersatu’s moral compass appeared broken, and its politics reduced to survival and convenience rather than principle.

Today, the internal feuding—Wan Saiful’s rebellion, Azmin’s re-emergence, and Muhyiddin’s tightening grip—reflects a party eating itself from within.

Its leaders, once united by the ambition to seize power, are now divided by personal rivalry and political fatigue.

Public trust in Bersatu has sharply declined, especially among younger and urban Malay voters who view the party as synonymous with political betrayal and instability.

Unless Bersatu undergoes a profound renewal of leadership and purpose, it risks fading into irrelevance—remembered not as the savior of Malay politics, but as the party that rose through betrayal and ultimately collapsed under the weight of its own hypocrisy.

I doubt we will see a renewal because Bersatu has no core leaders who are seen as political heavyweight and the party is not able to attract serious support from the Malay community.

Therefore, it is the least surprising if Bersatu sinks deeper into the abyss especially after certain elements in PAS are not keen to see Muhyiddin leading the opposition coalition, Perikatan Nasional.

As internal rifts deepen and electoral prospects dim, the party risks fading into political obscurity, unable to define its purpose beyond opposing the government.

As for Wan Saiful, not a known heavyweight, he would probably have to seek shelter in either PAS or Umno to harbor any hope of winning a parliamentary seat for the second time.

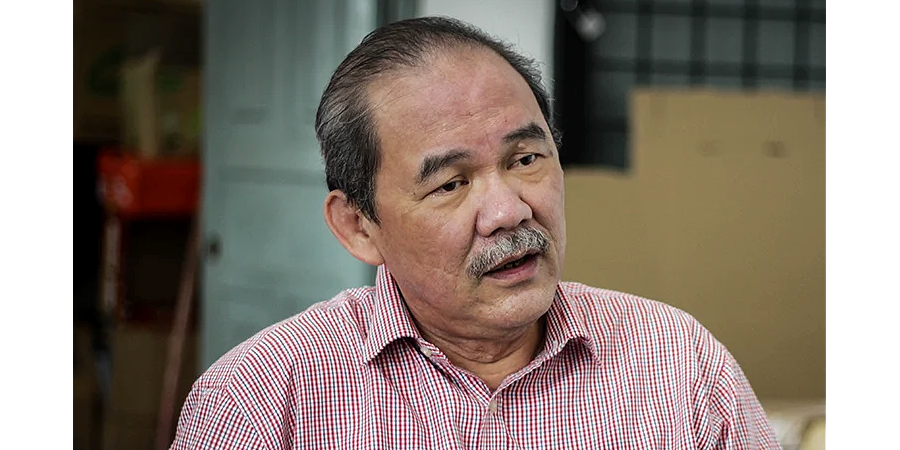

(Francis Paul Siah is a veteran Sarawak editor and currently heads the Movement for Change, Sarawak (MoCS). He can be reached at [email protected].)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT