In Malaysia, education has long been regarded by families of all ethnic groups as a means to change their fate and improve social status.

However, an unfair education system is hindering these dreams.

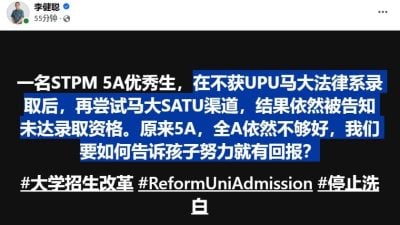

With the release of SPM and STPM results and the start of university applications, the issue of inequality in the country’s higher education system faced by non-Bumiputera students has once again come to the fore.

Many non-Malay students, despite achieving excellent academic results—even scoring 10As (including A-) in SPM—are still unable to gain entry into matriculation where they can only opt to sit for STPM, a channel seen as even more difficult which also takes up longer time.

Last year, Universiti Malaya’s medical faculty admitted 200 students, 73 of them Chinese. Only one of these 73 took STPM, showing how unfair the system is in entering public universities.

After completing SPM, non-Bumiputera students seeking to further their studies and enter public universities typically apply for the matriculation programs or enroll in Form 6 to sit for the STPM exam.

Originally, the matriculation program was exclusively for Bumiputera students. However in 2002, the government announced that 10 percent of intake would be open to non-Bumiputera students.

It is generally considered a shortcut to public universities, as the coursework is lighter, assessments are more flexible (including internal assessments and class participation), and university admission rates are higher.

Even though the matriculation program is technically open to non-Bumiputera students, the proportion of Chinese and Indian students accepted is extremely low. Outstanding students scoring 10A’s (including A-) in SPM are often rejected.

According to Education Minister Fadhlina Sidek, students who score an A- can still apply for matriculation via the “performance-based” evaluation system, but this introduces greater uncertainty.

University admissions should be based on merit. While reserving a quota for Bumiputera students is understandable, it must not be overly biased or implemented at the cost of other communities’ right to fair education.

Yet, the policy has seen little substantial change over the years.

STPM is generally regarded as more challenging than the matriculation program, and students experience greater academic and psychological pressure.

Although STPM is internationally recognized as an equivalent to A-Levels, systemic issues still prevent many high-performing non-Bumiputera students from gaining admission into popular university programs. This phenomenon has sparked public outcry and skepticism.

For decades, the public university admission system has operated under a dual-standard of “racial quota + academic performance.”

Admission is not purely merit-based, as the quota system absorbs a large portion of available spots.

Based on the standard practice of the Ministry of Education, 70 percent of matriculation students are guaranteed entry into local universities, while STPM students must compete for the remaining limited places.

Worse still, government scholarships and admissions often include a “Bumiputera-first” clause, making it difficult for Chinese and Indian students—even those with superior qualifications—to overcome this unfair barrier.

This extremely unjust system has harmed the futures of many outstanding non-Bumiputera students.

Families that invest heavily in their children’s education ultimately find them sidelined by an unfair system, forcing them to pursue studies abroad—a situation that damages national unity.

The progress of a nation begins with a fair education system. Only then can Malaysia retain its talent, develop the country, and realize the ideal of “shared progress for all.”

Brain drain comes at a high cost. In an era shaped by globalization and knowledge economy, talent is the most valuable national asset. Yet Malaysia faces a persistent crisis of talent loss.

A World Bank report from 2011 stated that more than 1 million Malaysians are living overseas, 67 percent being Chinese.

Today, an estimated 30,000 to 50,000 Malaysians still leave the country each year.

Reasons for brain drain include an unfair education system, unequal career advancement opportunities, political instability, and feelings of linguistic and cultural exclusion.

When talented young people cannot realize their dreams within the system, they naturally look abroad.

Many top students in medicine and engineering choose to study and settle in Singapore, Australia, the UK, Canada, and Taiwan.

This leads to domestic talent shortages, limiting development in healthcare, scientific research, and high-tech industries—creating a paradox where “the government supports Bumiputera students but loses the nation’s overall talent.”

As a long-time reformist who champions diversity, fairness, and openness, Prime Minister Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim has a duty to tackle the issue of inequality in the education system.

He must go beyond rhetoric about “national unity” and offer concrete reforms, gradually dismantling or restructuring the race-based admissions mechanism in favor of a need-based education system.

Here are some suggestions to be considered to improve the policy:

Gradually abolish or adjust the racial quota for matriculation program which should be transformed into a truly inclusive platform for higher education, with admission based on academic performance, family income, and regional disparities. Data should be transparently disclosed for social monitoring.

Ensure fairness in STPM pathways by enhancing STPM students’ admission to public universities, particularly in popular fields such as medicine and law so that they are not marginalized.

Consider implementing an “STPM outstanding student guaranteed admission scheme.”

Expand a unified university entrance exam system: Integrate STPM and matriculation into a single university admissions mechanism, using academic results as the sole criteria. This would prevent the confusion and injustice caused by multiple parallel tracks.

Launch a talent retention and repatriation program by offering incentives for students who study abroad to return—such as research grants, entrepreneurship funding, and relocation support—turning talent loss into an opportunity for renewal of resources.

If Malaysia truly wants to be a united, progressive, and modern multicultural country, it must be serious in tackling the long-standing inequality in its education system.

Otherwise, the continued exodus of talent will reflect the failure of our national policies.

Editor’s note: At 9 p.m. Wednesday (June 25), the Ministry of Education announced that the Cabinet has decided that students with A- grades will now be accepted into the matriculation program.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT