Tariff wars, historically, have been a blunt yet highly consequential tool of economic statecraft.

They do not merely serve as instruments of trade policy but also as weapons in broader geopolitical struggles.

As the world stands at the precipice of a full-scale global trade confrontation on April 2, 2025, the echoes of past economic crises – most notably the Great Depression – resonate with stark clarity.

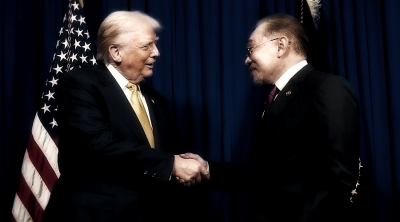

The impending escalation of tit-for-tat tariff measures by major economies, particularly in response to the revived protectionist push by the United States under President Donald Trump’s second administration, is eerily reminiscent of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

That legislation, originally intended to protect American farmers and industries from foreign competition, ultimately deepened the economic malaise of the Great Depression.

Could history be on the verge of repeating itself? More importantly, will April 2, 2025, be remembered as the day the global economy fundamentally changed?

From Smoot-Hawley to Trump’s tariff crusade

The Smoot-Hawley Act, signed into law by President Herbert Hoover, raised US tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods.

At the time, the rationale was simple: shield American workers and producers from foreign competition. However, the act triggered a wave of retaliatory tariffs from key trading partners, particularly in Europe and Canada, exacerbating the global economic downturn.

World trade collapsed, and what should have been a cyclical recession morphed into a prolonged depression.

Fast forward nearly a century, and Trump’s 2025 tariff strategy mirrors the same protectionist logic.

After returning to the White House, he swiftly enacted new tariff measures targeting China, the European Union, and even traditional allies like Japan and South Korea.

His administration, citing national security and unfair trade practices, imposed sweeping tariffs on technology, automobiles, semiconductors, and consumer goods.

This time, however, the international response has been much more coordinated and aggressive.

On April 2, 2025, the EU, China, and a bloc of emerging economies, including ASEAN, retaliated in unison. China imposed a 50 per cent tariff on American agricultural imports, effectively cutting off US farmers from one of their largest markets.

The EU slapped punitive tariffs on US technology firms, while ASEAN, for the first time in its history, acted collectively to introduce new trade barriers against American exports.

Even Japan and South Korea, long considered part of Washington’s economic sphere, joined in limited counter-measures.

The fragmentation of global economy

The significance of April 2, 2025, is not just in the tariffs themselves but in the broader fragmentation of the world economy that they represent.

For decades, the global economic system, anchored by institutions like the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank, functioned under the assumption that trade liberalisation was an irreversible trend.

Even during Trump’s first presidency (2017–2021), when he launched trade wars against China and the EU, the global economy adapted rather than fully fractured.

This time, the scale and speed of retaliation suggest a deeper structural shift.

The unified response of America’s trading partners reflects a fundamental loss of confidence in US economic leadership.

Whereas previous trade spats were seen as temporary disruptions, the coordinated countermeasures of April 2, 2025, signal a more permanent decoupling.

China has accelerated its push for an alternative trade order centred around the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

The EU has moved closer to finalising its economic partnership with ASEAN, reducing dependence on US markets.

Even Latin American economies, long reliant on access to US consumers, are actively seeking new trade alignments with China and the EU.

Protectionism does not make a nation great. It isolates, weakens, and ultimately undermines the very economic power it seeks to preserve.

De-dollarisation and the erosion of American financial power

One of the most significant yet underappreciated consequences of April 2, 2025, is its impact on the US dollar’s dominance.

In retaliation against Trump’s tariffs, China and Russia have intensified efforts to settle international trade in yuan and ruble, rather than dollar.

The EU, frustrated by Washington’s unilateral economic policies, has expanded the use of the euro in global trade settlements.

Even Middle Eastern oil producers, historically tied to the petrodollar system, are now diversifying their financial transactions.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE have started pricing some of their oil sales in yuan, signalling a potential shift away from the US-centric financial order.

If this trend continues, America’s ability to finance its massive deficits through the global demand for dollars could be at risk.

Winners and losers in the new economic order

While the immediate effects of the tariff war are economic disruptions, job losses, and increased inflation, the long-term implications will be even more profound.

China emerges as a relative winner: While Chinese exports to the US take a hit, Beijing’s aggressive push toward self-sufficiency in key sectors – particularly semiconductors and high-tech manufacturing – will reduce its long-term vulnerability.

Moreover, China’s vast consumer market allows it to absorb some of the shocks.

The EU gains economic leverage: By asserting itself as a leader of the global trade response, Brussels has enhanced its bargaining position.

The EU’s deepening ties with ASEAN and other regional blocs strengthens its economic clout.

ASEAN’s moment of strategic autonomy: For the first time, ASEAN is acting as a united economic entity rather than a passive observer of great power struggles.

By reducing dependence on the US market and diversifying trade relationships, ASEAN is positioning itself as a pivotal player in the evolving trade order.

The US faces economic isolation: While Trump’s supporters may hail the tariffs as a victory for American workers, the reality is stark.

Manufacturing costs rise due to higher-priced imports, farmers struggle with lost export markets, and US tech firms face increasing restrictions abroad.

The long-held assumption that America can dictate global economic rules unilaterally is being shattered.

Conclusion: A new global economic reality?

April 2, 2025, may go down in history as the day the world economy took a decisive turn away from US-led globalisation.

Just as Smoot-Hawley helped deepen the Great Depression, Trump’s aggressive tariff policies risk accelerating a global economic realignment that diminishes American economic influence.

The question now is whether Washington can recalibrate its strategy before it is too late.

Unlike in 1930, when economic collapse eventually led to the emergence of a new international trade order under US leadership, the present moment suggests that the world may be moving toward a multipolar economic system – one where America is no longer the unquestioned centre.

If history is any guide, protectionism does not make a nation great. It isolates, weakens, and ultimately undermines the very economic power it seeks to preserve.

On April 2, 2025, the world may have just crossed a point of no return.

(Prof Dr Phar Kim Beng is Expert Committee Member of the Centre of Regional Strategic Studies, CROSS, and Professor of ASEAN Studies at ISTAC-IIUM.)

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT