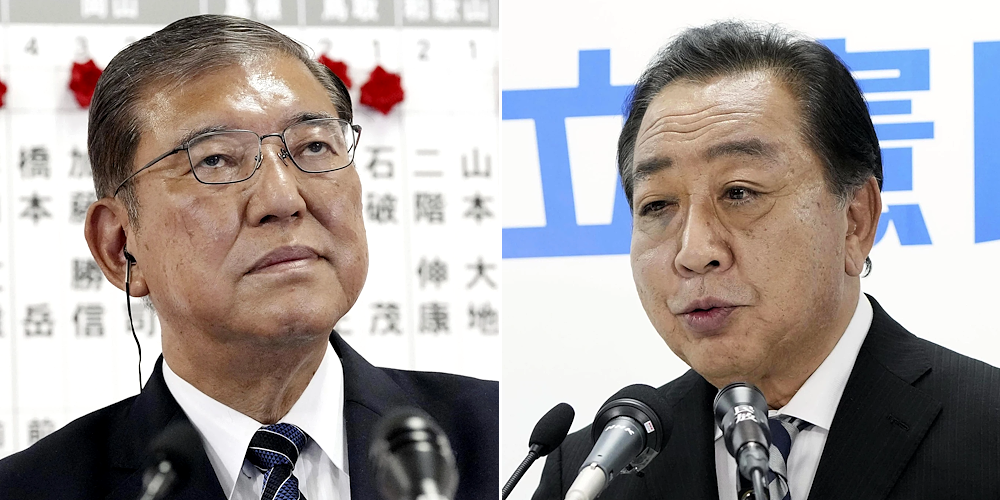

TOKYO: Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’ s ruling coalition lost a majority in the 465-seat lower house in a key parliamentary election Sunday, a punishment by voters’ outrage over the governing party’s extensive financial scandals.

Ishiba’s Liberal Democratic Party remains the top party in Japan’s parliament, and a change of government is not expected. But the results create political uncertainty.

Falling short of a majority makes it difficult for Ishiba to get his party’s policies through parliament, and he may need to find a third coalition partner.

The LDP’s coalition retains a majority in the less powerful upper house.

All told, the ruling coalition with junior partner Komeito secured 215 seats, down sharply from the majority of 279 it previously held, according to Japanese media.

It is the coalition’s worst result since briefly falling from power in 2009.

Ishiba took office on Oct. 1 and immediately ordered the election in hopes of shoring up support after his predecessor, Fumio Kishida, failed to address public outrage over the LDP’s scandals.

“The results so far have been extremely severe, and we take them very seriously,” Ishiba told Japan’s national NHK television late Sunday.

“I believe the voters are telling us to reflect more and become a party that lives up to their expectations.”

Ishiba said the LDP would still lead a ruling coalition and tackle key policies, compile a planned supplementary budget and pursue political reform.

He indicated that his party is open to cooperating with opposition groups if that suits the public’s expectations.

For Ishiba, potential additional partners include the Democratic Party of the People, which calls for lower taxes, and the conservative Japan Innovation Party.

DPP head Yuichiro Tamaki said he was open to “a partial alliance.”

Innovation Party chief Nobuyuki Baba has denied any intention to cooperate. The centrist DPP quadrupled to 28 seats, while the conservative Innovation Party slipped to 38.

Ishiba may also face backlash from a number of scandal-tainted lawmakers with former leader Shinzo Abe’s faction, whom Ishiba had un-endorsed for Sunday’s election in an attempt to regain public support.

The LDP is less cohesive now and could enter the era of short-lived prime ministers. Ishiba is expected to last at least until the ruling bloc approves key budget plans at the end of December.

“The public’s criticisms against the slush funds scandal has intensified, and it won’t go away easily,” said Izuru Makihara, a University of Tokyo professor of politics and public policy.

“There is a growing sense of fairness, and people are rejecting privileges for politicians.”

Makihara suggested Ishiba needs bold political reform measures to regain public trust.

A total of 1,344 candidates, including a record 314 women, ran for office in Sunday’s election.

In another blow to the ruling coalition, a number of LDP veterans who have served in Cabinet posts, as well as Komeito’s new leader, Keiichi Ishii, lost seats.

Experts say a CDPJ-led government is not in the picture because of its lack of viable policies.

“If they take power and try to change the economic and diplomatic policies of the current government, they will only end up collapsing right away,” Makihara said.

Realistically, Ishiba’s ruling coalition would seek a partnership with either the Innovation Party or the Democratic Party of the People, he said.

At a downtown Tokyo polling station, a number of voters said they had considered the corruption scandal and economic measures in deciding how to vote.

Once a popular politician known for criticism of even his own party’s policies, Ishiba has also seen support for his weeks-old Cabinet plunge.

Ishiba pledged to revitalise the rural economy, address Japan’s falling birth rate and bolster defence.

But his Cabinet has familiar faces, with only two women, and was seen as alienating members of the faction led by late premier Shinzo Abe.

Ishiba quickly retreated from earlier support for a dual surname option for married couples and legalising same-sex marriage, an apparent compromise to the party’s influential ultra-conservatives.

His popularity fell because of “the gap in what the public expected him to be as prime minister versus the reality of what he brought as prime minister,” said Rintaro Nishimura, a political analyst at The Asia Group.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT